Periodic table of protein complexes

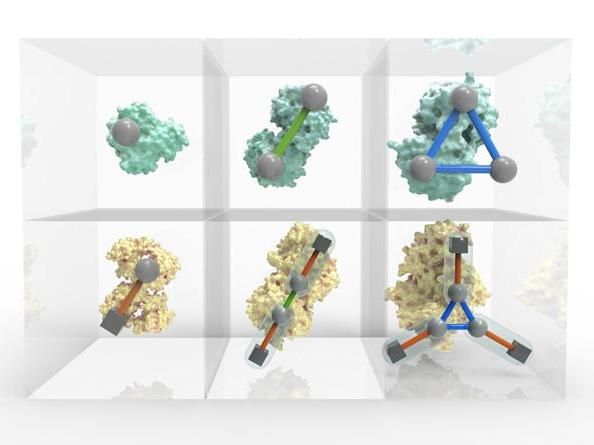

The Periodic Table of Protein Complexes offers a new way of looking at the enormous variety of structures that proteins can build in nature, which ones might be discovered next, and predicting how entirely novel structures could be engineered. Created by an interdisciplinary team led by researchers at the Wellcome Genome Campus and the University of Cambridge, the Table provides a valuable tool for research into evolution and protein engineering.

An interactive Periodic Table of Protein Complexes

EMBL-EBI / Spencer Phillips

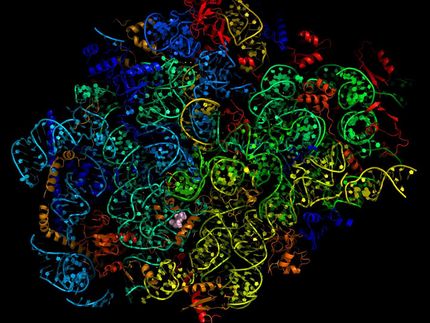

Almost every biological process depends on proteins interacting and assembling into complexes in a specific way, and many diseases are associated with problems in complex assembly. The principles underpinning this organisation are not yet fully understood, but by defining the fundamental steps in the evolution of protein complexes, the new 'periodic table' presents a systematic, ordered view on protein assembly, providing a visual tool for understanding biological function.

"Evolution has given rise to a huge variety of protein complexes, and it can seem a bit chaotic," explains Joe Marsh, formerly of the Wellcome Genome Campus and now of the MRC Human Genetics Unit at the University of Edinburgh. "But if you break down the steps proteins take to become complexes, there are some basic rules that can explain almost all of the assemblies people have observed so far."

Different ballroom dances can be seen as an endless combination of a small number of basic steps. Similarly, the 'dance' of protein complex assembly can be seen as endless variations on dimerization (one doubles, and becomes two), cyclisation (one forms a ring of three or more) and subunit addition (two different proteins bind to each other). Because these happen in a fairly predictable way, it's not as hard as you might think to predict how a novel protein would form.

"We're bringing a lot of order into the messy world of protein complexes," explains Sebastian Ahnert of the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, a physicist who regularly tangles with biological problems. "Proteins can keep go through several iterations of these simple steps, , adding more and more levels of complexity and resulting in a huge variety of structures. What we've made is a classification based on these underlying principles that helps people get a handle on the complexity."

The exceptions to the rule are interesting in their own right, adds Sebastian, as are the subject of on-going studies.

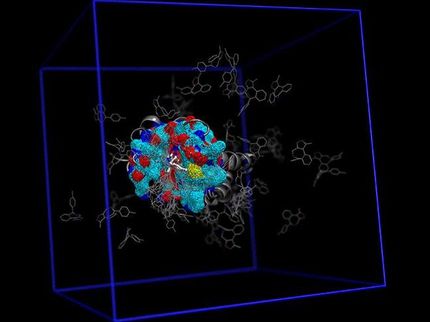

"By analysing the tens of thousands of protein complexes for which three-dimensional structures have already been experimentally determined, we could see repeating patterns in the assembly transitions that occur - and with new data from mass spectrometry we could start to see the bigger picture," says Joe.

"The core work for this study is in theoretical physics and computational biology, but it couldn't have been done without the mass spectrometry work by our colleagues at Oxford University," adds Sarah Teichmann, Research Group Leader at the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. "This is yet another excellent example of how extremely valuable interdisciplinary research can be."