Researchers grow retinal nerve cells in the lab

Johns Hopkins researchers have developed a method to efficiently turn human stem cells into retinal ganglion cells, the type of nerve cells located within the retina that transmit visual signals from the eye to the brain. Death and dysfunction of these cells cause vision loss in conditions like glaucoma and multiple sclerosis.

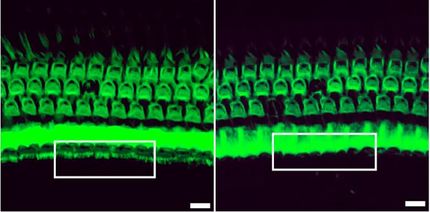

Fluorescence microscopy: Human retinal ganglion cells are shown at day 50.

Courtesy of Johns Hopkins Medicine; image provided by Valentin Sluch

"Our work could lead not only to a better understanding of the biology of the optic nerve, but also to a cell-based human model that could be used to discover drugs that stop or treat blinding conditions," says study leader Donald Zack, M.D., Ph.D., the Guerrieri Family Professor of Ophthalmology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "And, eventually it could lead to the development of cell transplant therapies that restore vision in patients with glaucoma and MS."

The laboratory process, described in the journal Scientific Reports, entails genetically modifying a line of human embryonic stem cells to become fluorescent upon their differentiation to retinal ganglion cells, and then using that cell line for development of new differentiation methods and characterization of the resulting cells.

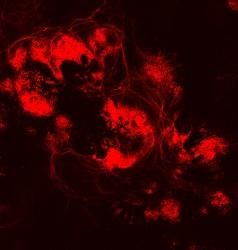

Using a genome editing laboratory tool called CRISPR-Cas9, investigators inserted a fluorescent protein gene into the stem cells' DNA. This red fluorescent protein would be expressed only if another gene was also expressed, a gene named BRN3B (POU4F2). BRN3B is expressed by mature retinal ganglion cells, so once a cell differentiated into a retinal ganglion cell, it would appear red under a microscope.

Next, they used a technique called fluorescence-activated cell sorting to separate out the newly differentiated retinal ganglion cells from a mixture of different cells into a highly purified cell population for study. The cells showed biological and physical properties seen in retinal ganglion cells produced naturally, says Zack.

Researchers also found that adding a naturally occurring plant chemical called forskolin on the first day of the process helped improve the cells' efficiency of becoming retinal ganglion cells. The researchers caution that forskolin, which is also widely available as a weight loss and muscle building supplement and is touted as an herbal treatment for a variety of disorders, is not scientifically proven safe or effective for treatment or prevention of blindness or any other disorder.

"By the 30th day of culture, there were obvious clumps of fluorescent cells visible under the microscope," says lead author Valentin Sluch, Ph.D., a former Johns Hopkins biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology student and now a postdoctoral scholar working at Novartis, a pharmaceutical company. Sluch completed this research at Johns Hopkins before transitioning to Novartis.

"I was very excited when it first worked," Sluch says. "I just jumped up from the microscope and ran [to get a colleague]. It seems we can now isolate the cells and study them in a pure culture, which is something that wasn't possible before."

"We really see this as just the beginning," adds Zack. In follow-up studies using CRISPR, his lab is looking to find other genes that are important for ganglion cell survival and function. "We hope that these cells can eventually lead to new treatments for glaucoma and other forms of optic nerve disease."

To use these cells to develop new treatments for MS, Zack is working with Peter Calabresi, M.D., professor of neurology and director of the Johns Hopkins Multiple Sclerosis Center.

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Gestational_diabetes

Sex_ratio

Category:Medical_associations

Gene recombination deactivates retroviruses during invasion of host genomes