Nano power grids between bacteria

Microorganisms in the sea organise their power supply via tiny power-cables, thus oxidising the greenhouse gas methane

Electrical energy from the socket - this convenient type of power supply is apparently used by some microorganisms. Cells can meet their energy needs in the form of electricity through nano-wire connections. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen have discovered these possibly smallest power grids in the world when examining cell aggregates of methane degrading microorganisms. They consist of two completely different cell types, which can only jointly degrade methane. Scientists have discovered wire-like connections between the cells, which are relevant in energy exchanges.

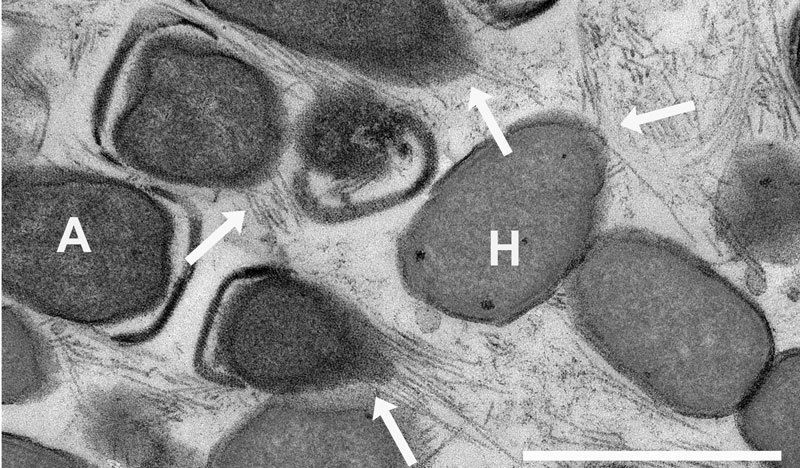

Electron micrograph of the nanowires connecting archaea and sulphate reducing bacteria. The wires stretch out for several micrometres, longer than a single cell. The white bar represents the length of one micrometre. The arrows indicate the nanowires (A=ANME-Archaeen, H=HotSeep-1 partner bacteria).

© MPI f. Biophysical Chemistry

It was a spectacular scientific finding when researchers discovered electrical wiring between microorganisms using iron as energy source in 2010. Immediately the question came up if electric power exchange is common in other microbially mediated reactions. One of the processes in question was the anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) that is responsible for the degradation of the greenhouse gas methane in the seafloor, and therefore has a great relevance for Earth climate. The microorganisms involved have been described for the first time in 2000 by researchers from Bremen and since then have been extensively studied.

The greenhouse gas methane in the seabed

In the ocean, methane is produced from the decay of dead biomass in subsurface sediments. The methane rises upwards to the seafloor, but before reaching the water column it is degraded by special consortia of archaea and bacteria. The archaea take up methane and oxidise it to carbonate. They pass on energy to their partner bacteria, so that the reaction can proceed. The bacteria respire sulphate instead of oxygen to gain energy (sulphate reducers). This may be an ancient metabolism, already relevant billions of years ago when the Earth’s atmosphere was oxygen-free. Yet today it remains unknown how the anaerobic oxidation of methane works biochemically.

Gunter Wegener, who authors the publication together with PhD student Viola Krukenberg, says: “We focused on thermophilic AOM consortia living at 60 degrees Celsius. For the first time we were able to isolate the partner bacteria to grow them alone. Then we systematically compared the physiology of the isolate with that of the AOM culture. We wanted to know which substances can serve as an energy carrier between the archaea and sulphate reducers.” Most compounds were ruled out quickly. At first, hydrogen was considered as energy source. However, the archaea did not produce sufficient hydrogen to explain the growth of sulphate reducers – hence the researchers had to change their strategy.

Direct power wires and electron transporters

One possible alternative was to look for direct connections channelling electrons between the cells. Using electron microscopy on the thermophilic AOM cultures this idea was confirmed. Dietmar Riedel, head of electron microscopy facilities at the Max Planck Institute in Goettingen says: “It was really challenging to visualize the cable-like structures. We embedded aggregates under high pressure using different embedding media. Ultrathin sections of these aggregates were then examined in near-native state using transmission electron microscopy.”

Viola Krukenberg adds: "We found all genes necessary for biosynthesis of the cellular connections called pili. Only when methane is added as energy source these genes are activated and pili are formed between bacteria and archaea.”

With length of several micrometres the wires can exceed the length of the cells by far, but their diameter is only a few nanometres. These wires provide the contact between the closely spaced cells and explain the spatial structure of the consortium, as was shown by a team of researchers led by Victoria Orphan from Caltech.

"Consortia of archaea and bacteria are abundant in nature. Our next step is to see whether other types also show such nanowire-like connections. It is important to understand how methane-degrading microbial consortia work, as they provide important functions in nature", explains Antje Boetius, leader of the research group at the Institute in Bremen.