Powerful plastic microscope brings better diagnostic care for world's rural poor

Advertisement

You can learn a lot about the state of someone's immune system just by examining their blood under the microscope. An abnormally high or low white blood count, for instance, might indicate a bone marrow pathology or AIDS. The rupturing of white blood cells might be the sign of an underlying microbial or viral infection. Strangely shaped cells often indicate cancer.

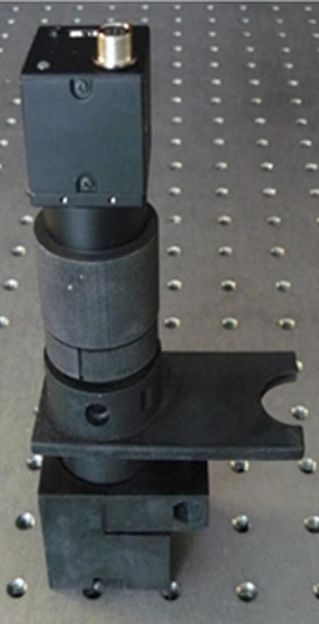

The assembled 3-D printed WBC microscope on an optical bench, with one inch spacing between the holes for reference.

Alessandra Forcucci, Rice University

While this old, simple technique may seem a quaint throwback in the age of high-technology health care tools like genetic sequencing, flow cytometry and fluorescent tagging, the high cost and infrastructure requirements of these techniques largely limit them to laboratory settings - something point-of-care diagnostics aims to fix. In a project funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation's Grand Challenges in Global Health Initiative, a research team from Rice University has recently developed a plastic, miniature digital fluorescence microscope that can quantify white blood cell levels in patients located in rural parts of the world that are far removed from the modern laboratory.

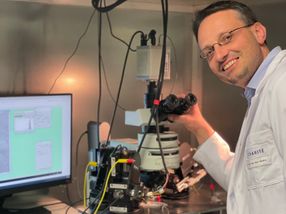

"One of the driving aspects of the project is the cost of the sample or sample preparation," said Tomasz Tkaczyk, associate professor, Department of Bioengineering, Rice University, Houston, Texas. "Many systems which work for point-of-care applications have quite expensive cartridges. The goal of this research is to make it possible for those in impoverished areas to be able to get the testing they need at a manageable price point."

Tkaczyk's co-authors on this research included Rebecca Richards-Kortum, Fellow of The Optical Society and a professor in Rice's Department of Bioengineering. Her research today involves translating molecular imaging research to point-of-care diagnostics.

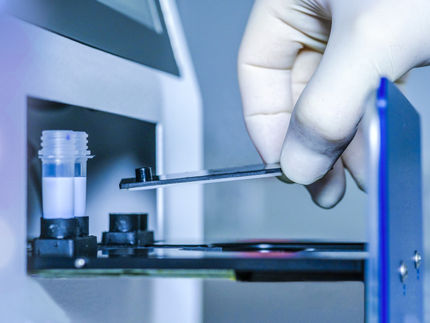

How the Microscope Works

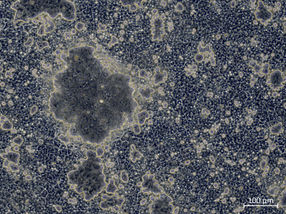

The researchers' device identifies and quantifies lymphocytes, monocytes, and granulocytes in a drop of blood mixed with the staining compound acridine orange. The compound is repelled by water at neutral pH, which allows it to easily diffuse through cellular and nuclear membranes, where it turns green or red when encountering DNA or RNA, respectively, with emission maximums at 525 nm and 650 nm. By optimizing a microscope for these emission peaks, the researchers are then able to quantify the white blood cells in a sample consisting only of 20 microliters of dye, 20 microliters of whole blood and a glass slide with a coverslip.

"You can just count cells," Tkaczyk said. "The device doesn't require the highest resolution, because we're not really focused on morphology here, but it needs to be able to resolve single cells, which are on the order of one micron or more."

The ratio in color allows the researchers to differentiate between monocytes, granulocytes and lymphocytes, which is significant because quantifying this three-part white blood cell count is an essential first step in diagnosing a number of disorders.

To fabricate the microscope's objective, which consisted of one polystyrene lens and two polymethyl methacrylate aspheric lenses, the researchers used a single-point diamond turning lathe. The lenses were then enclosed in an all-plastic, 3D-printed microscope housing and objective. Once constructed, the microscope provided a field of view of 1.2 millimeters, allowing for at least 130 cells to be present for statistical significance when quantifying white blood cells. Additionally, the microscope doesn't require any manual adjustment between samples once constructed.

The prototype microscope, which also includes an LED light source, power supply, control unit, optical system, and image sensor, cost less than $3,000 to construct. At production levels upwards of 10,000 units, the researchers estimate that this price would fall to around $600 for each unit, with a per-test cost of a few cents.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy has revolutionized life sciences, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. With its ability to visualize specific molecules and structures in cells and tissues through fluorescent markers, it offers unique insights at the molecular and cellular level. With its high sensitivity and resolution, fluorescence microscopy facilitates the understanding of complex biological processes and drives innovation in therapy and diagnostics.

Topic world Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy has revolutionized life sciences, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. With its ability to visualize specific molecules and structures in cells and tissues through fluorescent markers, it offers unique insights at the molecular and cellular level. With its high sensitivity and resolution, fluorescence microscopy facilitates the understanding of complex biological processes and drives innovation in therapy and diagnostics.