New optoelectronic probe enables communication with neural microcircuits

Advertisement

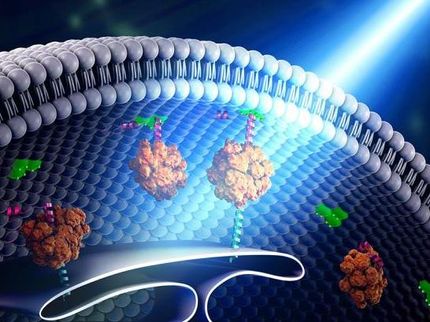

Researchers have created a new type of optoelectronic implantable device to access brain microcircuits, synergizing a technique that enables scientists to control the activity of brains cells using pulses of light. The invention, described in the journal Nature Methods, is a cortical microprobe that can stimulate multiple neuronal targets optically by specific patterns on micrometer scale while simultaneously recording the effects of that stimulation in the underlying neural microcircuits of interest with millisecond precision.

"We think this is a window-opener," said Joonhee Lee, a senior research associate in Professor Arto Nurmikko's lab in the School of Engineering at Brown and one of the lead authors of the new paper. "The ability to rapidly perturb neural circuits according specific spatial patterns and at the same time reconstruct how the circuits involved are perturbed, is in our view a substantial advance."

But until now, simultaneous optogenetic stimulation and recording of brain activity rapidly across multiple points within a brain microcircuit of interest has proven difficult. Doing it requires a device that can both generate a spatial pattern of light pulses and detect the dynamical patterns of electrical reverberations generated by excited cellular activity. Previous attempts to do this involved devices that cobbled together separate components for light emission and electrical sensing. Such probes were physically bulky, not ideal for insertion into a brain. And because the emitters and the sensors were necessarily a hundreds of micrometers apart, a sizable distance, the link between stimulation and recorded signal was ambiguous.

The new compact, integrated device developed by Nurmikko's lab begins with the unique advantages endowed by a so-called wide bandgap semiconductor called zinc oxide. It is optically transparent yet able readily to conduct an electrical current.

"Very few materials have that pair of physical properties," Lee said. "The combination makes it possible to both stimulate and detect with the same material."

Joonhee Lee, with Assistant Research Professor Ilker Ozden and Professor Yoon-Kyu Song at Seoul National University in Korea, co-developed a novel microfabrication method with Nurmikko to shape the material into a monolithic chip just a few millimeters square with sixteen micrometer sized pin-like "optoelectrodes," each capable of both delivering light pulses and sensing electrical current. The array of optoelectrodes enables the device to couple to neural microcircuits composed of many neurons rather than single neurons.

Such ability to stimulate and record at the network level on spatial and time scales at which they operate is key, Nurmikko says. Brain functions are driven by neural circuits rather than single neurons.

"For example, when I move my hand, that's an example of action driven by specific network-level activity in the brain," he said. "Our new device approach gives scientists and engineers a tool in applying the full power of optogenetics as a means of neural stimulation, while providing the means to read activity of perturbed networks at multiple points at high spatial precision and time resolution."

Ozden led the initial testing of the device in rodent models. The researchers looked at the extent to which different light intensities could stimulate network activity. The tests showed that increasing optical power led to distinct recruitment of neuronal circuits revealing functional connectivity in the targeted network.

"We went over a range of optical power that was large--over three orders of magnitude--and in so doing we got a range of network-related responses, in particular we could replicate an activity pattern naturally occurring in the brain." Ozden said. "It gave us a new insight into how optogenetics operates on the network level. This gives us encouragement to go ahead and extend the repertoire and application of the device technology."