A better way to read the genome

Reading 'Choose Your Own Adventure' novels

Researchers have sequenced the RNA of the most complicated gene known in nature, using a hand-held sequencer no bigger than a cell phone.

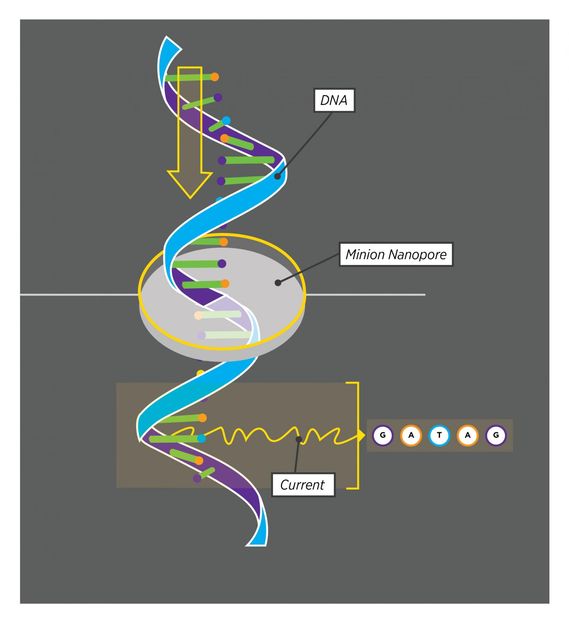

As a strand of DNA moves through the MinION nanopore, the MinION 'sees' five nucleotides at a time. Every set of five nucleotides produces a characteristic current, allowing the MinION to read out the DNA code in a single, continuous stream.

Yesenia Carrero/UConn

Genomicists Brenton Graveley from the UConn Institute of Systems Genomics, postdoctoral fellow Mohan Bolisetty, and graduate student Gopinath Rajadinakaran teamed up with UK-based Oxford Nanopore Technologies to show that the company's MinION nanopore sequencer can sequence genes faster, better, and at a much lower cost than the standard technology.

If your genome was a library and each gene was a book, some genes would be straightforward reads but for complicated choose-your-own-adventure genes, that has been impossible.

Graveley, Bolisetty, and Rajadinakaran solved the puzzle in two parts. The first was to find a better gene-sequencing technology. In order to sequence a gene using the old, existing technology, researchers first make lots of copies of it, using the same chemistry our bodies use. They then chop up the gene copies into tiny pieces, read each tiny piece, and then, by comparing all the different pieces, try to figure out how they were originally put together. The technique hinges on the likelihood that not all the copies got chopped up into exactly the same pieces. Imagine watching different scenes from a movie, out of order. If you then watched the same movie, but cut into scenes at slightly different places, you could compare the two versions and start to figure out which scenes connect to which.

That technique won't work for choose-your-own-adventure genes, because if you copy them the way the body does, using RNA, each copy can be different from the next. Such different versions of the same gene are called isoforms. When the different isoforms get chopped up and sequenced, it becomes impossible to accurately compare the pieces and figure out which versions of the gene you started with.

If the gene were a movie, "you wouldn't be able to tell that scenes 1 and 2 were present together," Bolisetty says.

Then last year, the nearly impossible suddenly became possible. Oxford Nanopore, a company based in the UK, released its new nanopore sequencer, and offered one to Graveley's lab. The nanopore sequencer, called a MinION, works by feeding a single strand of DNA through a tiny pore. The pore can only hold five DNA bases - the 'letters' that spell out our genes - at a time. There are four DNA bases, G, A, T, and C, and 1,024 possible five-base combinations. By feeding the DNA through the pore and recording the resulting signal, researchers can read the sequence of the DNA.

For the second part of the solution, Graveley, Bolisetty, and Rajadinakaran decided to go big. Instead of sequencing any old choose-your-own-adventure gene, they chose the most complex one known, Down Syndrome cell adhesion molecule 1 (Dscam1), which controls the wiring of the brain in fruit flies. Dscam1 has the potential of making 38,016 possible isoforms, and every fruit fly has the potential to make every one of them, yet how many of these versions are actually made remains unknown.

Dscam1 looks like this: X-12-X-48-X-33-X-2-X, where X's denote sections that are always the same, and the numbers indicate sections that can vary.

To study how many different isoforms of Dscam1 actually exist in a fly's brain, the researchers first had to convert Dscam1 RNA into DNA. The DNA includes the instructions for all 38,016 isoforms of the Dscam1 gene, while each individual Dscam1 RNA contains the instructions for just one. No one had yet used a MinION to sequence copies of RNA, and though it was likely it could be done, demonstrating it and showing how well it worked would be a substantial advance in the field.

Rajadinakaran took a fruit fly brain, extracted the RNA, converted it into DNA, isolated the DNA copies of the Dscam1 RNAs, and then ran them through the MinION's nanopores. In this one experiment, they not only found 7,899 of the 38,016 possible isoforms of Dscam1 were expressed but also that many more, if not all versions are likely to be expressed.