Relapse, poor survival in leukemia linked to genetic mutations that persist in remission

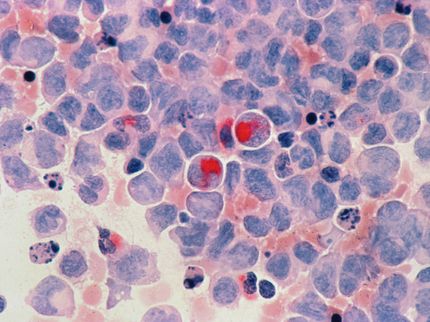

For patients with an often-deadly form of leukemia, new research suggests that lingering cancer-related mutations - detected after initial treatment with chemotherapy - are associated with an increased risk of relapse and poor survival.

Using genetic profiling to study bone marrow samples from patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), researchers found that those whose cells still carried mutations 30 days after the initiation of chemotherapy were about three times more likely to relapse and die than patients whose bone marrow was cleared of these mutations.

The study, by a team at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, is published in JAMA.

"Most patients diagnosed with AML fall into a gray area when it comes to being able to predict their risk of relapse," said senior author Timothy J. Ley, MD, the Lewis T. and Rosalind B. Apple Professor of Oncology in the Department of Medicine. "About 80 percent of AML patients go into remission with chemotherapy, but most of them eventually will relapse. Unfortunately, we still don't have a definitive test that tells us early on which patients will relapse.

"Such information is important to know because high-risk patients need aggressive, potentially curative therapy with a stem-cell transplant when they are in remission, early in the course of the disease. However, we don't want to transplant patients who are unlikely to relapse following conventional chemotherapy because the transplant procedure is expensive and carries a significant risk of severe side effects and even death."

The current study was retrospective, meaning that the researchers looked at bone marrow samples from patients whose outcomes were already known. The investigators studied leukemic bone marrow samples obtained at diagnosis from 71 AML patients treated at the Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University. Genome sequencing and analysis were performed at the university's McDonnell Genome Institute.

The researchers first sequenced the 71 bone marrow samples obtained at the time of diagnosis to see if specific leukemia-related mutations found in each patient's AML cells correlated with relapse after initial treatment with chemotherapy. But they found that such mutations were no more informative than standard methods for assessing risk of relapse.

The researchers then conducted genome sequencing on bone marrow samples that had been obtained from 50 patients at the time of diagnosis and again 30 days after the initiation of chemotherapy, when they were in remission. Analyzing these samples, the researchers found that 24 patients had persistent mutations in bone marrow cells after chemotherapy, even though by standard clinical measures they were in remission. This suggested that at least some leukemia cells had survived the initial therapy. In several cases, these same cells were shown to expand and contribute to relapse.

Those with persistent mutations had a median survival of only 10.5 months, compared with 42 months for the 26 patients whose leukemia mutations had been cleared by initial chemotherapy.

"If our results are confirmed in larger, prospective studies, genetic profiling after initial chemotherapy could help oncologists predict prognosis early in the course of a patient's leukemia and determine whether that patient has responded to the chemotherapy - without having to wait for the cancer to recur," said first author Jeffery M. Klco, MD, PhD, now at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. "This approach to genetic profiling, which focuses on performing genome sequencing after a patient's initial treatment, also may be useful for other cancers."

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Best of both worlds: Combining two skeleton-building chemical reactions

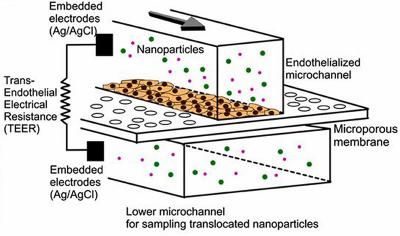

Testing nanomedicine with blood cells on a microchip