Can a viral co-infection impair immunity against Plasmodium and turn malaria lethal?

Advertisement

It is known that infections with certain viruses can weaken the immune response to another pathogen. A study published in PLOS Pathogens reports provocative findings in mice that infection with the mouse equivalent of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) can turn infections with certain parasites that cause malaria in mice (which are normally quickly suppressed by the immune system) into a lethal disease.

This is an immune-fluorescence staining of cross section of whole spleen. Gre B220 marker for B cells, Red: CD3 marker for T cells, and Blue: GL7 marker for germinal center cells.

Matar et al., CC-BY

In Sub-Saharan Africa, infants are infected with EBV, a gammaherpesvirus that infects B cells and, like HIV, remains present throughout the lifetime of the host. Children infected with EBV who live in areas where malaria is common have an increased risk of developing Burkitt's lymphoma, a cancer linked to EBV.

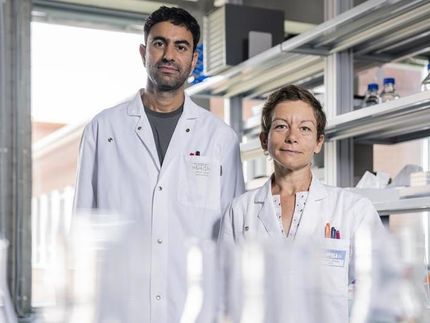

To investigate whether EBV infection could also affect the course of malaria disease, a team of researchers led by Tracey Lamb and Samuel Speck, both from Emory University, Atlanta, USA, studied the consequences of co-infection with of a gammaherpesevirus and two different parasites that cause malaria in mice.

Where normally immune cells expand and mount a rapid and precise defense against an intruder, acute murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV68) infections of mice, like acute EBV infections in humans, can induce a transient suppression of the antibody immune response during a subsequent infection by another pathogen.

The researchers used two well-established non-lethal strains of mouse parasites called Plasmodium yoelii XNL and P. chabaudi AS, and determined that acute MHV68 infection can suppress the anti-malarial antibody response during co-infection with either of these Plasmodium strains. This immune suppression resulted in loss of control of the P. yoelii parasites and transformed the usually non-lethal infection into a lethal one characterized by severe malarial anemia. (Immunity against P. chabaudi depends less on antibody-mediated immunity, and those parasites remained controlled.)

Examining the mechanism by which the virus impaired the anti-malaria immune response, the researchers found that the reduced anti-Plasmodium antibody response during co-infection coincided with the knock-out of a critical component of an immune response to a known pathogen--the so-called T follicular helper cells in the spleen.

Loss of these T helper cells resulted in loss of pathogen-specific B cells (the precursors of antibody-producing plasma cells) and a failure to develop sufficient plasma cell numbers to produce anti-Plasmodium antibodies that could control the infection. The researchers also identified that a specific protein of the MHV68 virus called M2 is essential for suppression of the anti-Plasmodium antibody response causing lethal malaria in the mice.

"Our work", the researchers conclude, "provides compelling evidence that acute gammaherpesvirus infection can negatively modulate the humoral immune response to malaria infection". There are few human and no large epidemiological studies exploring a possible link between EBV infection and severe malarial anemia, but the researchers suggest that their mouse data are consistent with the existing human evidence on the immunosuppressive effects of EBV and justify investigation of "how EBV infection might impact the development of P. falciparum humoral immunity in young children living in malaria endemic areas".