Proteins pull together as cells divide

Group dynamics, not star proteins, drive mechanics of crucial cell process

Advertisement

Like a surgeon separating conjoined twins, cells have to be careful to get everything just right when they divide in two. Otherwise, the resulting daughter cells could be hobbled, particularly if they end up with too many or two few chromosomes. Successful cell division hangs on the formation of a dip called a cleavage furrow, a process that has remained mysterious. Now, researchers at Johns Hopkins have found that no single molecular architect directs the cleavage furrow's formation; rather, it is a robust structure made of a suite of team players. The finding is detailed in Current Biology.

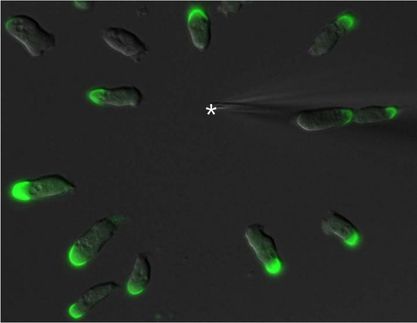

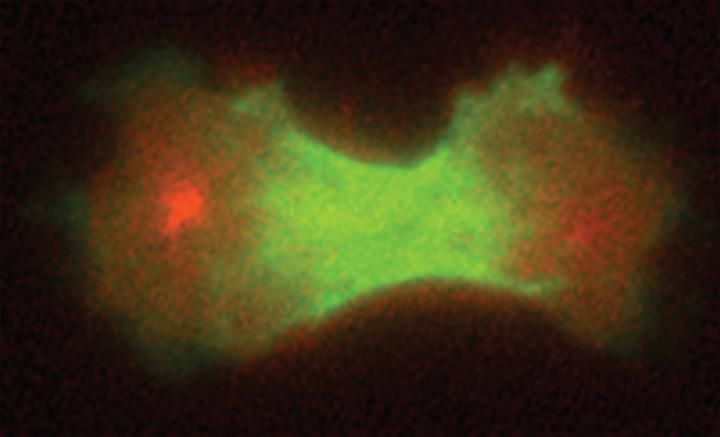

A cleavage furrow begins to separate a dividing cell into daughter cells.

Janet Effler/Johns Hopkins Medicine

"We assumed the cleavage furrow was like a finely tuned Swiss watch, in that breaking a key component would bring it to a stop -- we just didn't know what that component was," says Douglas Robinson, Ph.D., a professor of cell biology in the Institute for Basic Biomedical Sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, borrowing an analogy from the late Ray Rappaport, the founding father of modern cell division research. "But it turned out to be more like an old Maine fishing boat: almost indestructible."

Cell division is how new cells form, both during development and throughout an organism's life. To learn more about this process, Robinson and graduate student Vasudha Srivastava took the one-celled amoeba Dictyostelium as their model. One by one, they disabled genes for proteins known to be involved in the cleavage furrow to see whether doing so disrupted its assembly. But no matter which protein was taken out, other proteins still self-assembled to form the cleavage furrow. "It's not a house of cards -- pulling out one protein doesn't bring it down," Srivastava says. Instead, she and Robinson found a robust process tuned not only by chemical signaling, but also by mechanical processes.

That makes sense, Robinson says, given the importance of the cleavage furrow to life itself. "Cells need to get division right in order to avoid ending up with the wrong number of chromosomes, which can be fatal," he says.