Why do new strains of HIV spread slowly?

Advertisement

Most HIV epidemics are still dominated by the first strain that entered a particular population. New research published in PLOS computational biology offers an explanation of why the global mixing of HIV variants is so slow.

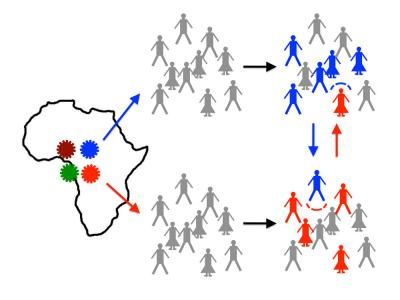

Single strains of HIV entered distinct populations across the world to establish local epidemics. Once established, these epidemics are resilient to the introduction of new strains, thus conserving "founder effects."

Ferdinandy et al.

Researchers from Eötvös Loránd University; Bence Ferdinandy, Dr Viktor Müller, and colleagues, analyzed simulated epidemics to understand how distinct HIV virus strains spreading in the same population compete and interfere with each other.

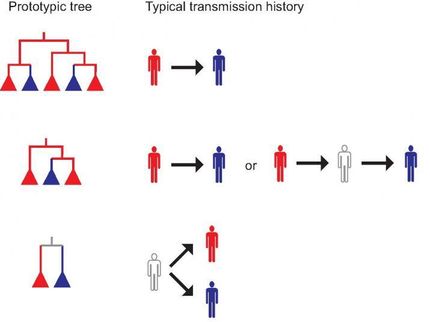

The authors show that once a strain of HIV has established a stable epidemic, it can slow down the invasion of secondary strains into the population. The primary factor is because individuals infected with the first HIV strain survive for a relatively long time and are resilient to 'superinfection' from a second strain. The individuals effectively impose 'roadblocks' for the spread of invader strains in the network of sexual contacts.

The results imply that the HIV variants that dominate the global epidemic today may not be the most transmissible strains: they may simply have been the 'luckiest', picked up by chance to ride the first wave of expansion from the epicenter of the pandemic in Central Africa.

More transmissible strains are likely to exist or be created by mutation and recombination, and these strains may eventually outgrow the current variants, a warning that the pandemic is not 'static': it may grow further on a longer time scale. In contrast, eliminating the epidemic could increase the risk of emergent HIV lineages from novel cross-species transmissions.