'Virtual breast' could improve cancer detection

Advertisement

Next to lung cancer, breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in women, according to the American Cancer Society. That's why so many medical professionals encourage women to get mammograms, even though the tests are imperfect at best: only a minority of suspicious mammograms actually leads to a cancer diagnosis.

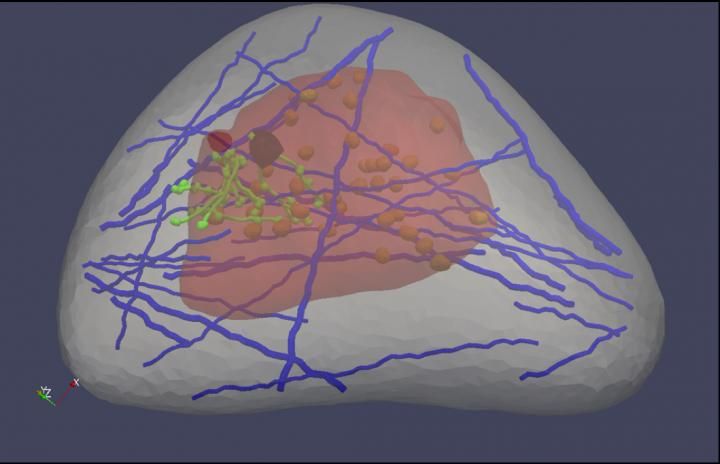

A 'virtual breast' image, part of a software program designed by Michigan Tech's Jingfeng Jiang. The software is designed to train health professionals how to read ultrasound elastography images used to detect cancer. More-accurate interpretations would help eliminate unnecessary biopsies and other treatments stemming from false-positive mammograms.

Jingfeng Jiang

That results in lots of needless worry for women and their families—not to mention the time, discomfort and expense of additional tests, including ultrasounds and biopsies.

Recently, a different type of test, ultrasound elastography, has been used to pinpoint possible tumors throughout the body, including in the breast. "It uses imaging to measure the stiffness of tissue, and cancer tissues are stiff," says Jingfeng Jiang, a biomedical engineer at Michigan Technological University. Those images can be breathtakingly clear: Jiang shows one elastogram in which the tumor is as different from normal breast tissue as a yolk is from the white in a fried egg. However, not all images are that precise.

"Depending on who does the reading, the accuracy can vary from 95 percent to 40 percent," he said. "Forty percent is very bad—you get 50 percent when you toss a coin. In part, the problem is that ultrasound elastography is a new modality, and people don't know much about it."

Ultrasound elastography could be an excellent screening tool for women who have suspicious mammograms, but only if the results are properly interpreted. Jiang, who helped develop ultrasound elastography when he was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, reasoned that clinicians might improve their accuracy if they could practice more. So he and his colleagues set about to build a virtual breast.

Like a simulator used to train fledgling surgeons, their virtual breast—a 3D, computer-generated "phantom"—would let medical professionals practice in the safety of the lab. It was developed using data from the Visible Human Project, which gathered thousands of cross-sectional photos from a female cadaver. Thus, it mimics the intricacy of the real thing, incorporating a variety of tissue types and anatomical structures, such as ligaments and milk ducts.

Clinicians can practice looking for cancer by applying virtual ultrasound elastography to the virtual breast and then evaluating the resulting images. Jiang hopes that eventually the lab software will be available to anyone who needs the training.