Breakthrough study discovers 6 changing faces of 'global killer' bacteria

Researchers unlock vital new information to improve vaccinations against pneumococcus infection

Advertisement

Every ten seconds a human being dies from Streptococcus pneumoniae infection, also known as pneumococcus, making it a leading global killer.

An interdisciplinary team of researchers from the University of Leicester in collaboration with international experts have unlocked a genetic switch controlling the disease - which can cause pneumonia and other invasive infections – that could pave the way to improved vaccines.

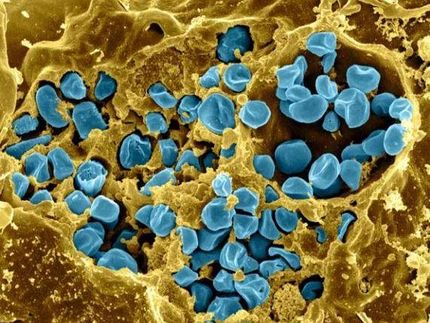

Pneumococcus is a pathogenic bacterium and the leading cause of serious illness across the globe. It is the main cause of pneumonia, sinusitis, blood infections, meningitis, and middle ear infections, known as otitis media. Pneumococcal disease affects children and the elderly, and it is one of the leading infectious diseases worldwide.

The study, which has been peer reviewed and published in the journal Nature Communications, was co-authored by Professor Marco Oggioni from the University of Leicester's Department of Genetics with an international team including Professor Michael Jennings from Griffith University's Institute for Glycomics, Professor James Paton from the University of Adelaide and scientists from Pacific Biosciences, and has for the first time shown a genetic switch that allows this bacterium to randomly change its characteristics into six alternative states.

The discovery indicates the ability of the pneumococcus to cause deadly infections is different in each of these six states and each form is randomly generated by a phase variable methylation system, as if the bacteria were playing dice and assigning themselves to any one of the six potential outcomes. Some states favour harmless colonisation or spread from person to person, while others favour invasive, life-threatening disease.

Professor Oggioni said: "Facing a bacterial with six and more phase variable systems is like being simultaneously confronted with six different bacteria; it gives them an unfair advantage, but knowing the genetic basis now places us in an optimal position to reinvestigate drug and vaccine efficacy."

To support the findings the team required careful mathematical analysis of the data, which was carried out by a team led by Alexander Gorban, Professor of Applied Mathematics at the University of Leicester's Department of Mathematics.

Professor Gorban said: "The study led to an interesting puzzle about statistics of relative positions of markers on DNA. It was our pleasure to modify the classical methods and to solve this puzzle. We are happy that this work arose while trying to answer an important microbiological problem."

Professor Michael Jennings, Deputy Director of the Institute for Glycomics at Griffith University, describes the study as a significant breakthrough.

He added: "By use of the latest DNA sequencing technology from Pacific Biosciences we have shown that the pneumococcus generates subpopulations that have distinct DNA methylation patterns and we have shown that these epigenetic changes alter both gene expression patterns and virulence."

"Each time this bacterium divides it is like throwing a dice. Any one of six different cell types can appear. Understanding the role this six way switch plays in pneumococcal infections is key to understanding this disease and is crucial in the development of new and improved vaccines."

Professor Paton, Director of the Research Centre for Infectious Diseases at the University of Adelaide concurred, adding: "In this game of dice the stakes are very high, with each roll of the dice having a major impact on survival of either the bacterium or its human host."