A new piece in the autism puzzle

Spontaneous mutations in key brain gene are a cause of the disorder

Disorders such as autism are often caused by genetic mutations. Such mutations can change the shape of protein molecules and stop them from working properly during brain development. However, the genetic foundation of autism is complicated and there is no single genetic cause. In some individuals, inherited genetic variants may put them at risk. But research in recent years has shown that severe cases of autism can result from new mutations occurring in the sperm or egg - these genetic variants are found in a child, but not in his or her parents, and are known as de novo mutations. Scientists have sequenced the DNA code of thousands of unrelated children with severe autism and found that a handful of genes are hit by independent de novo mutations in more than one child. One of the most interesting of these genes is TBR1, a key gene in brain development. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, Netherlands, describe how mutations in TBR1 disrupt the function of the encoded protein in children with severe autism. In addition, they uncover a direct link between TBR1 and FOXP2, a well-known language-related protein.

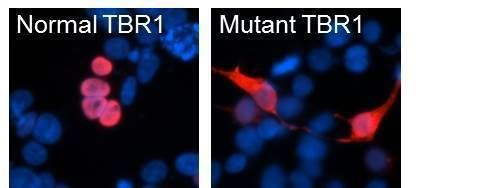

Mutations in the TBR1 gene in children with autism affect the location of the TBR1 protein in human cells. In cells, the normal TBR1 protein, shown in red, is found together with DNA, shown in blue. In contrast, the mutant TBR1 protein is found throughout the cell.

© MPI f. Psycholinguistics/ Deriziotis

Autism is a disorder of brain development which leads to difficulties with social interaction and communication. One third of individuals never learn to speak, whereas others can speak fluently but have difficulties maintaining a conversation and understanding non-literal meanings. Studying autism can therefore help us understand which brain circuits underlie social communication, and how they develop.

In the new study, researchers from the Max Planck Institute’s Language and Genetics Department, together with colleagues from the University of Washington, investigated the effects of autism risk mutations on TBR1 protein function. The scientists were interested in directly comparing the de novo and inherited mutations found in autism, because it is speculated that de novo mutations have more severe effects. They used several cutting-edge techniques to examine how the mutations affected the way the TBR1 protein works, using human cells grown in the laboratory. According to the scientists de novo mutations disrupt subcellular localization of TBR1. ‘We found that the de novo mutations had much more dramatic effects on TBR1 protein function compared to the inherited mutations that we studied’, says lead author Pelagia Deriziotis, ‘It is a really striking confirmation of the strong impact that de novo mutations can have on early brain development’.

The human brain depends on many different genes and proteins working together in combination. So, novel research horizons could be opened up by identifying proteins that interact with TBR1. ‘We can think of it like a social network for proteins’, says Deriziotis, ‘There were initial clues that TBR1 might be "friends" with a protein called FOXP2. This was intriguing because FOXP2 is one of the few proteins to have been clearly implicated in speech and language disorders’. The researchers discovered that, not only does TBR1 directly interact with FOXP2, mutations affecting either of these proteins abolish the interaction.

According to senior author Simon Fisher, ‘It is very exciting to uncover these fascinating molecular links between different disorders that affect language. By coupling data from genome screening with functional analysis in the lab, we are starting to build up a picture of the neurogenetic pathways that contribute to fundamental human traits.’

Original publication

Pelagia Deriziotis et al.; De novo TBR1 mutations in sporadic autism disrupt protein functions; Nature Communications, 18 September 2014