Long Antibiotic Treatments: Slowly Growing Bacteria to Blame

Advertisement

Whether pneumonia or sepsis – infectious diseases are becoming increasingly difficult to treat. One reason for this is the growing antibiotic resistance. But even non-resistant bacteria can survive antibiotics for some time, and that’s why treatments need to be continued for several days or weeks. Scientists at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel showed that bacteria with vastly different antibiotic sensitivity coexist within the same tissue. In the scientific journal Cell they report that, in particular, slowly growing pathogens hamper treatment.

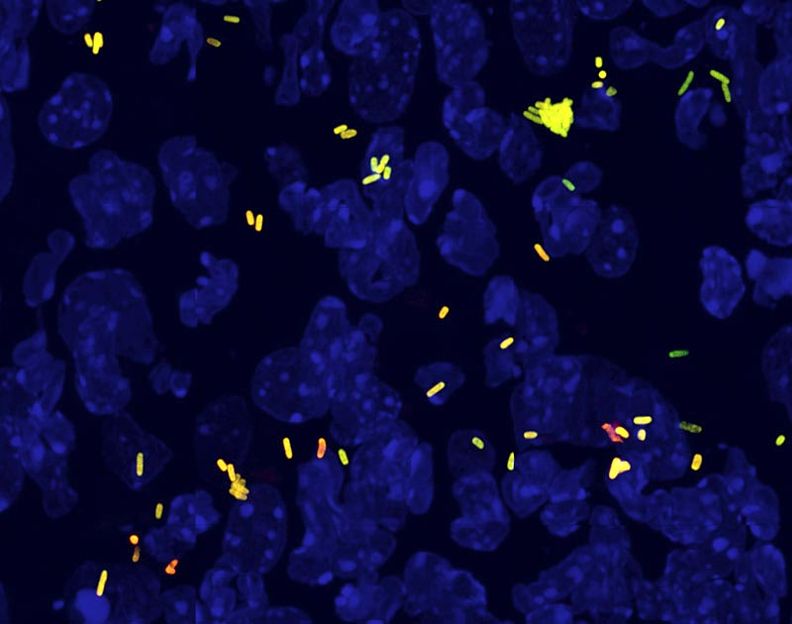

Infected mouse spleen containing fast (green) and slow (orange) growing Salmonella (blue: nuclei of mouse cells).

University of Basel, Biozentrum

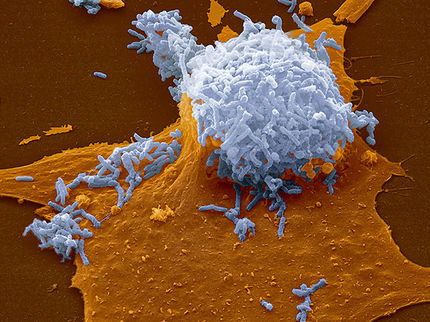

Many bacteria are principally susceptible to treatment, but can still survive for some hours to days in adverse environmental conditions, such as exposure to antibiotics. It is commonly assumed that these pathogens are in a type of “dormancy” state. They don’t grow and thus become invulnerable against the effects of many antibiotics. However, Prof. Dirk Bumann and his team at the University of Basel's Biozentrum, demonstrated that dormant pathogens play only a minor role in Salmonella-infected tissue. Instead, abundant slowly growing bacteria are the biggest challenge for treatment.

Salmonella grows at different rates

Genetically identical bacteria can grow at very different rates, even within the same test tube. Is this also true for pathogens in infected host tissues? Bumann used a new method based on fluorescent colors, to measure the proliferation of individual Salmonella. The results revealed that in host tissues some Salmonella grow very rapidly, producing many daughter cells, which cause increasingly severe disease. Most bacteria, however, reside in tissue regions with limited nutrient supply, in which they grow only slowly.

Slow growth ensures survival

How do these diverse growth rates impact on the success of antibiotic therapy? Therapy of infected mice quickly ameliorated disease signs, but even after five days of treatment, some bacteria still survived in the tissues, posing a risk for relapse. “We could kill already 90 percent of the Salmonella with the first antibiotic dose, particularly those that grew rapidly”, reports Bumann, “but non-growing Salmonella survived much better. Treatment success thus depended on the Salmonella replication rate.”

This observation could support the current research focus on “dormant” bacteria. However, Bumann was surprised that such bacteria were actually not the biggest challenge for treatment. “Instead, slowly growing Salmonella are more important. They tolerate antibiotics less well compared to dormant bacteria, but they are present in much larger numbers, and readily restart their growth once antibiotic levels in the tissue drop, thus driving infection and relapse. As a result, slowly growing pathogens dominate throughout the entire therapy. A better understanding of bacterial physiology of such slowly growing bacteria, could help us to shorten the duration of treatment with a more specifically targeted antibiotic therapy.” This is particularly interesting for infectious diseases that currently require medication over several weeks or even months, to prevent a recurrence of the infection.