Coral reefs provide potent new anti-HIV proteins

Discovery raises hope for new methods to prevent the spread of HIV

Researchers have discovered a new class of proteins capable of blocking the HIV virus from penetrating T-cells, raising hope that the proteins could be adapted for use in gels or sexual lubricants to provide a potent barrier against HIV infection.

The proteins, called cnidarins, were found in a feathery coral collected in waters off Australia's northern coast. Researchers zeroed in on the proteins after screening thousands of natural product extracts in a biorepository maintained by the National Cancer Institute. "It's always thrilling when you find a brand-new protein that nobody else has ever seen before," said senior investigator Barry O'Keefe, Ph.D., deputy chief of the Molecular Targets Laboratory at the National Cancer Institute's Center for Cancer Research. "And the fact that this protein appears to block HIV infection—and to do it in a completely new way—makes this truly exciting."

In the global fight against AIDS, there is a pressing need for anti-HIV microbicides that women can apply to block HIV infection without relying on a man's willingness to use a condom. Koreen Ramessar, Ph.D., a postdoctoral research fellow at the National Cancer Institute and a member of the research team, said cnidarins could be ideally suited for use in such a product because the proteins block HIV transmission without encouraging the virus to become resistant to other HIV drugs.

"When developing new drugs, we're always concerned about the possibility of undermining existing successful treatments by encouraging drug resistance in the virus," said O'Keefe. "But even if the virus became resistant to these proteins, it would likely still be sensitive to all of the therapeutic options that are currently available."

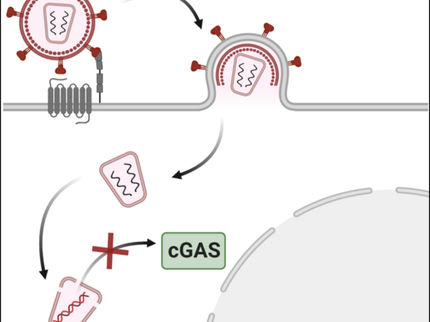

The research team identified and purified the cnidarin proteins, then tested their activity against laboratory strains of HIV. The proteins proved astonishingly potent, capable of blocking HIV at concentrations of a billionth of a gram by preventing the first step in HIV transmission, in which the virus must enter a type of immune cell known as the T-cell.

"We found that cnidarins bind to the virus and prevent it from fusing with the T-cell membrane," said Ramessar. "This is completely different from what we've seen with other proteins, so we think the cnidarin proteins have a unique mechanism of action."

The next step is to refine methods for generating cnidarins in larger quantities so the proteins can be tested further to identify potential side effects or activity against other viruses. "Making more of it is a big key," said O'Keefe. "You can't strip the Earth of this coral trying to harvest this protein, so our focus now is on finding ways to produce more of it so we can proceed with preclinical testing."

The scientists discovered cnidarins while screening for proteins, a largely understudied component of natural product extracts found in the National Cancer Institute's extract repository. The institute maintains a large collection of natural specimens gathered from around the world under agreements with their countries of origin. The specimens are available to researchers across the United States.

"The natural products extract repository is a national treasure," said O'Keefe. "You never know what you might find. Hopefully, discoveries like this will encourage more investigators to use this resource to identify extracts with activity against infectious disease."

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents