Function found for mysterious heart disease gene

Advertisement

A new study from researchers at the University of Ottawa heart Institute (UOHI), published in Cell Reports, sheds light on a mysterious gene that likely influences cardiovascular health. After five years, UOHI researchers now know how one genetic variant works and suspect that it contributes to the development of heart disease through processes that promote chronic inflammation and cell division.

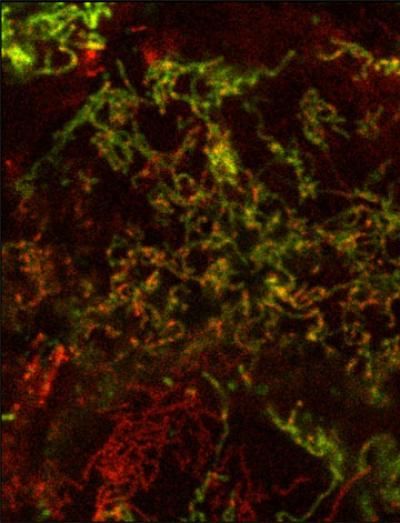

A genetic variant of the gene SPG7 is associated with increased risk of heart disease. University of Ottawa Heart Institute researchers have shown that this variant increases cardiovascular risk by initiating oxidative stress in mitochondria (shown in red) that leads to chronic inflammation and long-term damage of blood vessels. The mitochondria in an unstressed cell would show primarily as green.

University of Ottawa Heart Institute

Researchers at the Ruddy Canadian Cardiovascular Genetics Centre had initially identified a variant in a gene called SPG7 as a potential contributor to coronary artery disease several years ago, but its role in multiple health processes made it difficult to tease out how it affects heart disease.

The gene holds instructions for producing a protein called SPG7. This protein resides in mitochondria—the small power plants of cells that produce the energy cells need to function. SPG7's role is to help break down and recycle other damaged proteins within the mitochondria.

Normally, SPG7 requires a partner protein to activate itself and start this breakdown process. But, in people who carry the genetic variant in question, SPG7 can activate itself in certain circumstances, leading to increased production of free radicals and more rapid cell division. These factors contribute to inflammation and atherosclerosis.

"We think this variant would definitely heighten the state of inflammation, and we know that inflammation affects diabetes and heart disease," said Dr. Stewart, Principal Investigator in the Ruddy Canadian Cardiovascular Genetics Centre and senior author of the study. "Interestingly, the variant also makes people more resistant to the toxic side effects of some chemotherapy drugs."

From an evolutionary perspective, this resistance could help such a genetic variant gain a stable place in the human genome. Between 13 and 15 per cent of people of European descent possess this variant.

"The idea of mitochondria contributing to inflammation isn't new," concluded Dr. Stewart. "But what is new is that we've found one of the switches that regulate this process. We're excited, because once you know where the switches are, you can start looking for ways to turn them on and off."