How mechanical forces affect T-cell recognition and signaling

T-cells are the body's sentinels, patrolling every corner of the body in search of foreign threats such as bacteria and viruses. receptor molecules on the T-cells identify invaders by recognizing their specific antigens, helping the T-cells discriminate attackers from the body's own cells. When they recognize a threat, the T-cells signal other parts of the immune system to confront the invader.

These T-cells use a complex process to recognize the foreign pathogens and diseased cells. In a paper published this week in the journal Cell, researchers add a new level of understanding to that process by describing how the T-cell receptors (TCR) use mechanical contact – the forces involved in their binding to the antigens – to make decisions about whether or not the cells they encounter are threats.

"This is the first systematic study of how T-cell recognition is affected by mechanical force, and it shows that forces play an important role in the functions of T-cells," said Cheng Zhu, a Regents' professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University. "We think that mechanical force plays a role in almost every step of T-cell biology."

The researchers, who were supported by the National Institutes of Health, made their discoveries using a tiny sensor based on a single red blood cell and a new technique for detecting calcium ions emitted by the T-cells as part of the signaling process. They independently studied the binding of antigens to more than a hundred individual T-cells, measuring the forces involved in the binding and the lifetimes of the bonds. That information was then correlated to the calcium signaling they observed.

Among the findings, the researchers learned that interactions between the TCRs and agonist peptide-major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) form catch bonds that become stronger with the application of additional force to initiate intracellular signaling. Less active MHC complexes form slip bonds that weaken with force and don't initiate signaling. Overall, they found that the signaling outcome of an interaction between an antigen and a TCR depends on the magnitude, duration, frequency and timing of the force application.

"Force adds another dimension to interactions with T-cells," Zhu explained. "Antigens that have a bond lifetime that is prolonged by force would have a higher likelihood of triggering signaling. Repeat engagements and lifetime accumulations play a role, and the decision to signal is usually made based on the accumulation of actions, not a single action."

He compared the force component of T-cell activation to multiple steps needed to enter a person's office inside a secured building. A key card and a personal identification number may first be necessary to enter the building, while an ordinary key might then be needed to get into a specific office. Requiring both recognition of an antigen and specific level of mechanical force may help the T-cell avoid activating when it shouldn't, Zhu said.

Zhu compared the accumulation of bonds to the punches that a boxer sustains during a fight. A rare very hard single punch, or a series of lesser blows over a short period of time, can both lead to a knockout. But a series of light blows over a longer time may have no effect, Zhu said.

Researchers already have other examples of how mechanical force can affect the operation of cellular systems. For instance, mechanical stress created by blood flow acting on the endothelial cells that line blood vessel walls plays a role in the disease atherosclerosis. Force is also necessary for proper bone growth and healing. That mechanical forces would also play a role in the immune system therefore isn't surprising, Zhu said.

"We now have a broader recognition that the physical environment and mechanical environment regulate many of the biological phenomena in the body," he said. "When you exert a force on the TCR bonds, some of them dissociate faster, while others come off more slowly. This has an effect on the response of the T-cell receptor."

In their experiments, Zhu and collaborators Baoyu Liu, Wei Chen and Brian Evavold used a biomembrane force probe to measure the strength and longevity of bonds between T cells and antigens. The probe consists, in part, of a red blood cell aspirated to a micropipette. Attached to the red blood cell is a bead on which researchers place the antigen under study. Using a delicate mechanism that precisely controls motion, the bead is then moved into contact with a T-cell receptor, allowing binding to take place.

To test the strength of bond formed between an antigen and the TCR, the researchers apply piconewton forces to separate the bead holding the antigen from the TCR. The red blood cell acts as a spring, stretching and allowing a measurement of the forces that must be applied to separate the TCR and antigen. The technique, which requires motion control at the nanometer scale, allows measurement of binding between the antigen and a single TCR.

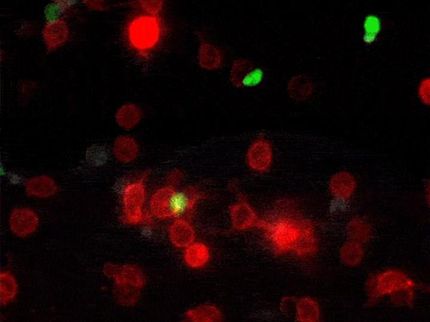

To assess the impact of the binding on intracellular signaling, the researchers inject a dye into the cells that fluoresces when exposed to the calcium signaling ions. Detecting the fluorescence allowed the researchers to know when the mechanical force triggered T-cell signaling.

"We can directly look at kinetics and signaling at the same time," explained Liu, a research scientist in the Coulter Department and co-first author of the paper. "We can observe the signaling directly induced by TCR interactions."

As a next step, Zhu's team would like to explore the effects of force on development of T-cells using the new experimental techniques. Evidence suggests that the forces to which the cells are exposed while they are in a juvenile stage may affect the fates of their development.