Novel understanding of onion-like carbon nanoparticles

Advertisement

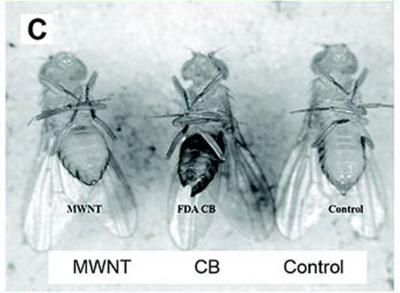

Symmetry is ubiquitous in the natural world. It occurs in gemstones and snowflakes and even in biology, an area typically associated with complexity and diversity. There are striking examples: the shapes of virus particles, such as those causing the common cold, are highly symmetrical and look like tiny footballs.

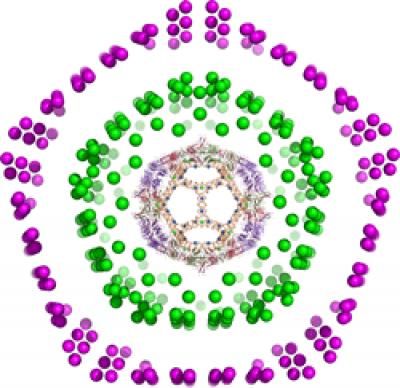

This image shows a virus nested within fullerene cages called carbon onions.

Dechant et al.

A research programme led by Reidun Twarock at the University of York, UK has developed new mathematical tools to better understand the implications of this high degree of symmetry in these systems. The group pioneered a mathematical theory that reveals unprecedented insights into how different components of a virus, the protein container encapsulating the viral genome and the packaged genome within, mutually constrain each other's structures.

A paper recently published in Acta Crystallographica in collaboration with Pierre-Philippe Dechant from the University of Durham, UK shows that these mathematical tools apply more widely in the natural world and interestingly also account for the structures of Russian-doll-like arrangements of carbon cages known as carbon onions. It was known previously that individual shells could be modeled using symmetry techniques, but the fact that the entire structure is collectively constrained by a single symmetry principle is a surprising new result.

Such insights are crucial for understanding how different components contribute collectively to function. In the case of viruses this work has resulted in a new understanding of the interplay of the viral genome and protein capsid in virus formation, which in turn has opened up novel opportunities for anti-viral intervention that are actively being explored. Similarly, we expect that the work on carbon onions will provide a basis for a better understanding of the structural constraints on their overall organisation and formation, which in the future can be exploited in nanotechnology applications.