Gene found to be crucial for formation of certain brain circuitry

Identified using new technique that can speed identification of genes, drug candidates

Using a powerful gene-hunting technique for the first time in mammalian brain cells, researchers at Johns Hopkins report they have identified a gene involved in building the circuitry that relays signals through the brain. The gene is a likely player in the aging process in the brain, the researchers say. Additionally, in demonstrating the usefulness of the new method, the discovery paves the way for faster progress toward identifying genes involved in complex mental illnesses such as autism and schizophrenia — as well as potential drugs for such conditions. A summary of the study appears in Cell Reports.

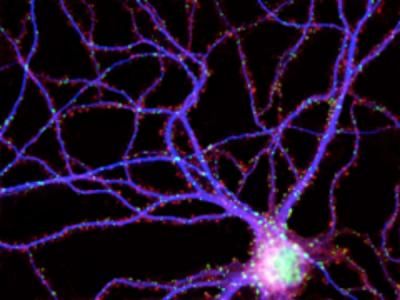

This is a mouse neuron with synapses shown: Red dots mark excitatory synapses, while green dots mark so-called inhibitory synapses.

Kamal Sharma/Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

"We have been looking for a way to sift through large numbers of genes at the same time to see whether they affect processes we're interested in," says Richard Huganir, Ph.D., director of the Johns Hopkins University Solomon H. Snyder Department of Neuroscience and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, who led the study. "By adapting an automated process to neurons, we were able to go through 800 genes to find one needed for forming synapses — connections — among those cells."

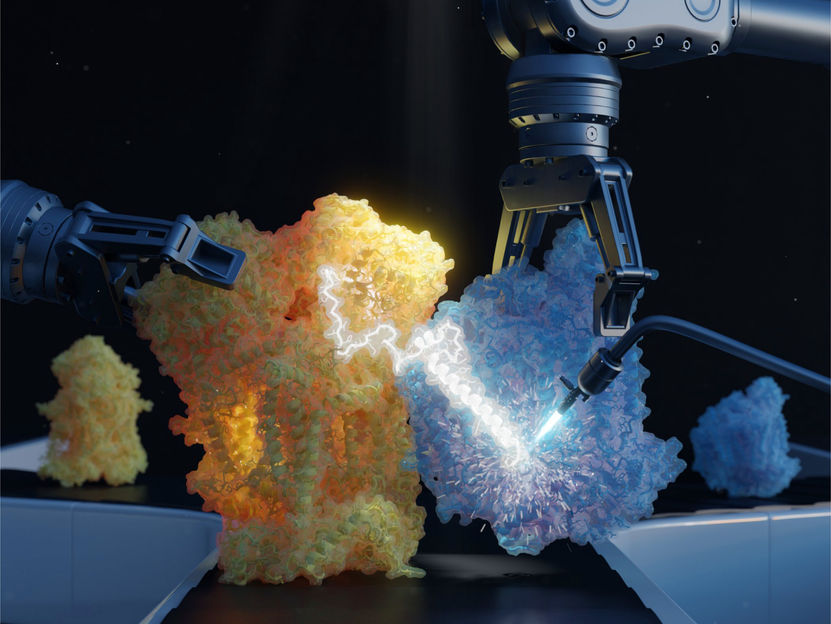

Although automated gene-sifting techniques have been used in other areas of biology, Huganir notes, many neuroscience studies instead build on existing knowledge to form a hypothesis about an individual gene's role in the brain. Traditionally, researchers then disable or "knock out" the gene in lab-grown cells or animals to test their hypothesis, a time-consuming and laborious process.

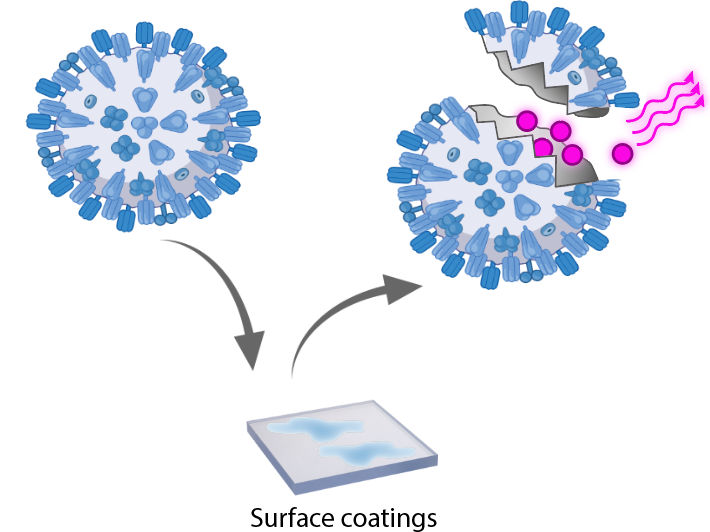

In this study, Huganir's group worked to test many genes all at once using plastic plates with dozens of small wells. A robot was used to add precise allotments of cells and nutrients to each well, along with molecules designed to knock out one of the cells' genes — a different one for each well.

"The big challenge was getting the neurons, which are very sensitive, to function under these automated conditions," says Kamal Sharma, Ph.D., a research associate in Huganir's group. The team used a trial-and-error approach, adjusting how often the nutrient solution was changed and adding a washing step, and eventually coaxed the cells to thrive in the wells. In addition, Sharma says, they fine-tuned an automated microscope used to take pictures of the circuitry that had formed in the wells and calculated the numbers of synapses formed among the cells.

The team screened 800 genes in this way and found big differences in the well of cells with a gene called LRP6 knocked out. LRP6 had previously been identified as a player in a biochemical chain of events known as the Wnt pathway, which controls a range of processes in the brain. Interestingly, Sharma says, the team found that LRP6 was only found on a specific kind of synapse known as an excitatory synapse, suggesting that it enables the Wnt pathway to tailor its effects to just one synapse type.

"Changes in excitatory synapses are associated with aging, and changes in the Wnt pathway in later life may accelerate aging in general. However, we do not know what changes take place in the synaptic landscape of the aging brain. Our findings raise intriguing questions: Is the Wnt pathway changing that landscape, and if so, how?" says Sharma. "We're interested in learning more about what other proteins LRP6 interacts with, as well as how it acts in different types of brain cells at different developmental stages of circuit development and refinement."

Another likely outcome of the study is wider use of the gene-sifting technique, he says, to explore the genetics of complex mental illnesses. The automated method could also be used to easily test the effects on brain cells of a range of molecules and see which might be drug candidates.