The yin and yang in the life of proteins

Two opposing mechanisms regulate the transport of proteins in peroxisomes

Recycling or “scrap press”: physicians at the Ruhr-Universität have found out which molecular mechanisms decide about the fate of the import receptor Pex18. Pex18 is responsible for the import of proteins into specific cell components, namely peroxisomes. Two opposing regulatory circuits determine whether the receptor remains active or is broken down after the transport has been completed. “Thus, the picture of the regulation of the protein import into peroxisomes has been completed and integrated to form one single model,” says Junior Professor Dr Harald Platta from the RUB Faculty of Medicine.

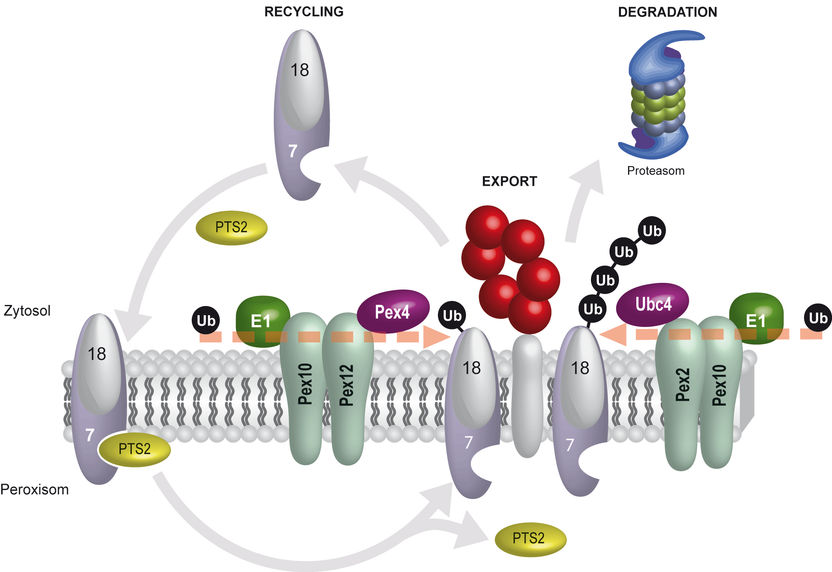

Peroxisomal protein transport model: The import receptor for peroxisomal PTS2 proteins is the two-part receptor complex Pex18/Pex7. After the PTS2 protein has been released into the interior of the peroxisome, the receptor is exported. Docking an ubiquitin (Ub) with Pex18 sends out the signal that the receptor can be recycled for new import reactions. The docking of the individual ubiquitins is determined by the E1 enzyme, the E2 enzyme Pex4p as well as the E3 enzymes Pex12/Pex10. If an ubiquitin chain forms at Pex18, the proteasome breaks down Pex18. Docking of the ubiquitin chain is effected through the E1 enzyme, the E2 enzyme Ubc4 as well as the E3 enzymes Pex2/Pex10.

© RUB, Grafik: Platta

Ubiquitin signals determine the fate of the receptors

Because they don’t have their own DNA, peroxisomes have to import all proteins that are necessary for them to fulfil their function. For this purpose, the cell is equipped with dynamic import receptors such as Pex18. They bind proteins in the cytoplasm and transport them to the peroxisome. The RUB team had demonstrated in a previous study that the signal protein ubiquitin subsequently decides about the future fate of the receptors: if a single ubiquitin protein docks with the receptor, the receptor gets recycled; it migrates back into the cytoplasm and launches a new transport process. If an ubiquitin chain docks with the receptor, a signal is sent out for the receptor to be broken down by the proteasome, an “intracellular scrap press”, so to speak. Prior to this discovery, it had not been understood in what way the cell determines on the molecular level what happens to the receptor.

Recycling or “scrap press”: It all depends on the enzyme cascade

The RUB physicians found out that different enzyme cascades catalyse the two ubiquitin modifications of Pex18. In both cases, it is a three-step process: the E1 enzyme activates the ubiquitin signal which is subsequently transferred by the E2 enzyme and, eventually, coordinated by the E3 enzyme to dock with the receptor. By analysing yeast cells, the Bochum physicians found out that E2 and E3 enzymes occur in different variations, whereas there is only one type of the E1 enzyme. The docking of one single ubiquitin and an ubiquitin chain is determined by different combinations of E2 and E3 enzymes. “That means two opposing molecular machines determine the fate of the import receptor Pex18,” says Harald Platta. “This discovery illustrates just how precisely the receptor’s control is calibrated and how precisely the regulation associated with it is effected for the entire peroxisomal function. This project constitutes a crucial foundation for further research into the molecular causes of peroxisomal disorders.”

Peroxisomes: The cell’s multi-functional tools

Peroxisomes are important reaction states within the cell. They may contain up to 50 enzymes which are crucial for breaking down of fatty acids, for the disposal of hydrogen peroxide and the generation of plasmalogens which are an important component of the brain’s white matter. A disruption of the protein import in peroxisomes has a negative impact on the entire metabolism and may be fatal – especially for newborns.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Castleman's_disease

Ultrasound activates anticancer agent - New active substance unfold its cell-damaging effect only where it is supposed to

John_Alexander_Hopps

Hepatocellular_carcinoma

Putting a bull's-eye on the flu: Detailing influenza's structure for drug targeting

En Carta Diagnostics secures €1.5M to advance diagnostic kit platform for early Lyme disease detection - Groundbreaking patented molecular diagnostic kit poised to provide game-changing autonomous Lyme detection in minutes

Ribosomal_Binding_Site

Category:Antiglucocorticoids

Starlab Minizentrifuge | Mini centrifuges | STARLAB

Anal_sac_adenocarcinoma

When and why does type 1 diabetes manifest in children? - New findings on the development of the autoimmune disease in children