Microneedle patch could replace standard tuberculosis skin test

Advertisement

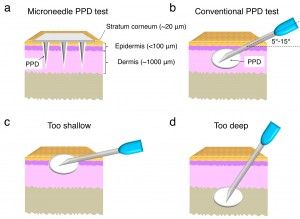

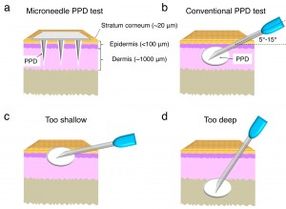

Each year, millions of people in the United States get a tuberculosis skin test to see if they have the infection that still affects one-third of the world’s population. But the standard diagnostic test is difficult to give, because a hypodermic needle must be inserted at a precise angle and depth in the arm to successfully check for tuberculosis.

A chitin microneedle patch tested on human skin.

Marco Rolandi, UW

Comparison of a microneedle tuberculosis test with a traditional test administered with a hypodermic needle. The lower images show needle-depth problems that can occur with the conventional test.

Marco Rolandi, UW

Now, a team led by University of Washington engineers has created a patch with tiny, biodegradable needles that can penetrate the skin and precisely deliver a tuberculosis test. The researchers published their results online in the journal Advanced Healthcare Materials.

“With a microneedle test there’s little room for user error, because the depth of delivery is determined by the microneedle length rather than the needle-insertion angle,” said senior author Marco Rolandi, a UW assistant professor of materials science and engineering. “This test is painless and easier to administer than the traditional skin test with a hypodermic needle.”

A tuberculosis test is a common precautionary measure for teachers, health care professionals and international travelers. The bacterial infection usually attacks the lungs and can live in an inactive state for years in the body. A diagnostic test involves an injection in a person’s arm. Within two or three days, a swollen, firm bump will appear if an infection is present.

Rolandi’s lab and collaborators at the Infectious Disease Research Institute in Seattle believe this is the first time microneedles made from biomaterials have been used as a diagnostic tool for tuberculosis. They say their test will be easier to use, less painful and has the potential to be more successful than the standard tuberculosis skin test.

The researchers tested the patch on guinea pigs and found that after the microneedles were inserted using the patch, the skin reaction associated with having a tuberculosis infection was the same as when using the standard hypodermic needle test. A microneedle patch test has potential as a simpler, more reliable option than the traditional tuberculosis test for children who are needle-shy, or in developing countries where medical care is limited, Rolandi said.

“It’s like putting on a bandage,” Rolandi said. “As long as the patch is applied on the skin, the test is always delivered to the same depth underneath the skin.”

With the standard test, if a hypodermic needle is inserted at the wrong angle, the solution to check for tuberculosis is injected too deep or too shallow into the skin, and the test fails.

Microneedles have been used in recent years as a painless alternative to hypodermic needles to deliver drugs to the body. Microneedles on a patch can be placed on an arm or leg, which then create small holes in the skin’s outermost layer, allowing the drugs coated on each needle to diffuse into the body.

Microneedles are made from silicon, metals and synthetic polymers, and most recently of natural, biodegradable materials such as silk and chitin, a material found in hard outer shells of some insects and crustaceans.

The UW team developed microneedles made from chitin that are each 750 micrometers long, or about one-fortieth of an inch. Each needle tip is coated with purified protein derivative, the material used for testing for tuberculosis. The researchers found that these microneedles were strong enough to penetrate the skin and deliver the tuberculosis test.

“It’s a great application of this technology and I hope it will become a commercial product,” said paper co-author Darrick Carter, a biochemist and a vice president at the Infectious Disease Research Institute.

The researchers will continue developing the microneedle tuberculosis test and plan to test it next on humans. They also hope to develop different diagnostic tests using microneedles, including allergy tests.