Problem-solving governs how we process sensory stimuli

Various areas of the brain process our sensory experiences. How the areas of the cerebral cortex communicate with each other and process sensory information has long puzzled neuroscientists. Exploring the sense of touch in mice, brain researchers from the University of Zurich now demonstrate that the transmission of sensory information from one cortical area to connected areas depends on the specific task to solve and the goal-directed behavior. These findings can serve as a basis for an improved understanding of cognitive disorders.

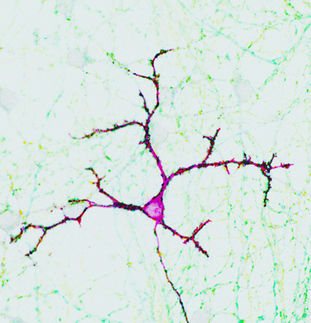

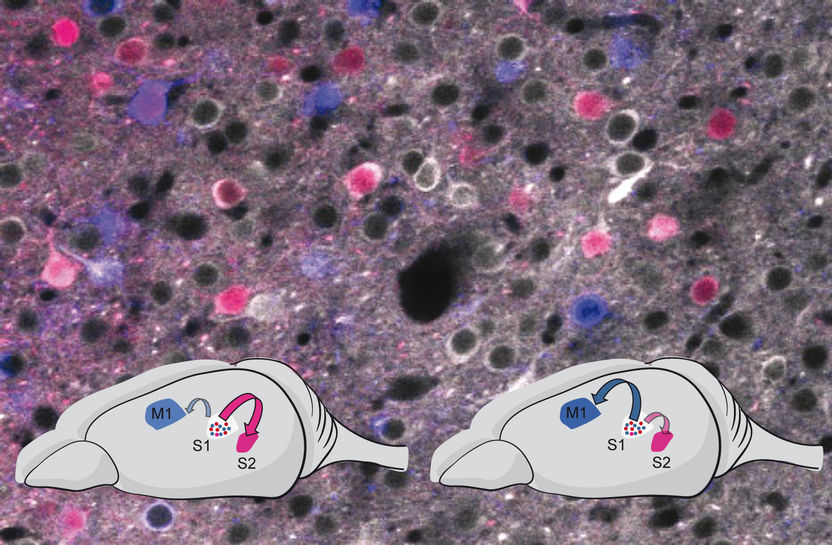

Nerve cells in the primary somatosensory area (S1) of the mouse’s cerebral cortex. Cells dyed violet project to the secondary somatosensory area (S2), cells dyed blue to the motor cortex (M1). The strength of the schematic representation of the communication between the areas depends on the tasks to be performed: left, sandpaper differentiation; right, localization problem.

Jerry Chen, HiFo, UZH

In the mammalian brain, the cerebral cortex plays a crucial role in processing sensory inputs. The cortex can be subdivided into different areas, each handling distinct aspects of perception, decision-making or action. The somatosensory cortex, for instance, comprises the part of the cerebral cortex that primarily processes haptic sensations. The different areas of the cerebral cortex are interconnected and communicate with each other. A central, unanswered question of neuroscience is how exactly do these brain areas communicate to process sensory stimuli and produce appropriate behavior. A team of researchers headed by Professor Fritjof Helmchen at the University of Zurich’s Brain Research Institute now provides an answer: The processing of sensory information depends on what you want to achieve. The brain researchers observed that nerve cells in the sensory cortex that connect to distinct brain areas are activated differentially depending on the task to be solved.

Goal-directed processing of sensory information

The researchers studied how mice use their facial whiskers to explore their environment, much like we do in the dark with our hands and fingers. One mouse group was trained to distinguish coarse and fine sandpapers using their whiskers in order to obtain a reward. Another group had to work out the angle, at which an object – a metal rod – was located relative to their snout. The neuroscientists measured the activity of neurons in the primary somatosensory cortex using a special microscopy technique. With simultaneous anatomical stainings they also identified which of these neurons sent their projections to the more remote secondary somatosensory area and the motor cortex, respectively.

The primary somatosensory neurons with projections to the secondary somatosensory cortex predominantly became active when the mice had to distinguish the surface texture of the sandpaper. Neurons with projections to the motor cortex, on the other hand, were more involved when mice needed to localize the metal rod. These different activity patterns were not evident when mice passively touched sandpaper or metal rods without having been set a task – in other words, when their actions were not motivated by a reward. Thus, the sensory stimuli alone were not sufficient to explain the different pattern of information transfer to the remote brain areas.

Impaired communication in the brain

According to Fritjof Helmchen, the activity in a cortical area can be transmitted to remote areas in a targeted fashion if we have to extract ('filter') specific information from the environment to solve a problem. In cognitive disorders such Alzheimer’s disease, Autism, and Schizophrenia, this communication between brain areas is often disrupted. “A better understanding of how these long-range, interconnected networks in the brain operate might help to develop therapies that re-establish this specific cortical communication,” says Helmchen. The aim would be to thereby improve the impaired cognitive abilities of patients.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Cerebellar_abiotrophy

Song_Changrong

New guidelines for development and approval of biosimilars move closer - EuropaBio welcomes the direct dialogue and calls upon the EU to settle all outstanding important issues before the first biosimilars enter the market

Three-dimensional model of bacterium - New methods of electron microscopy decode the structure of Gemmata obscuriglobus

Brief_therapy

Therapies_under_investigation_for_multiple_sclerosis

Hypotonic

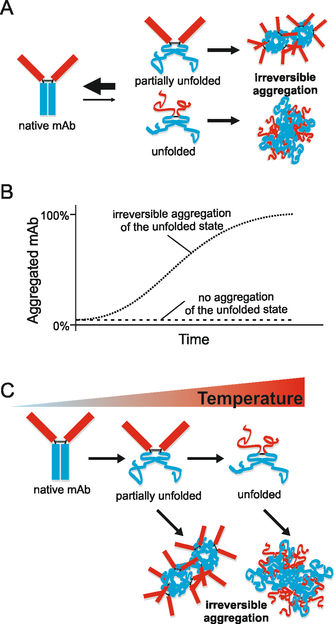

Predicting the Long-Term Stability of Biologics - Analysis of Formulation-Dependent Colloidal and Conformational Stability of Monoclonal Antibodies

Scientists find a brake that acts when cellular motors run too far - Cell-organisation better understood

BIOTECH AUSTRIA calls for better framework conditions for the biotechnology sector of the future - Proposals provide impetus for research, infrastructure and investments in Austria