Biologists take snapshot of fleeting protein process

Rice, BCM crystallographers capture elusive actin nucleation process

Advertisement

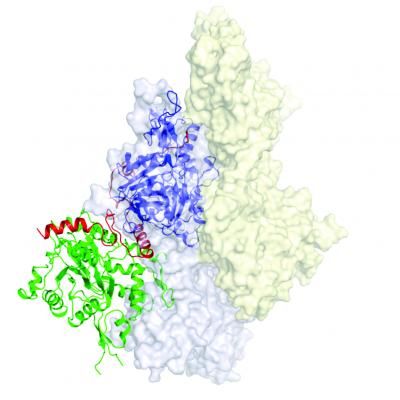

Structural biologists from Rice University and Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) have captured the first three-dimensional crystalline snapshot of a critical but fleeting process that takes place thousands of times per second in each human cell. The research appears online today in the journal Cell Reports and could prove useful in the study of cancer and other diseases.

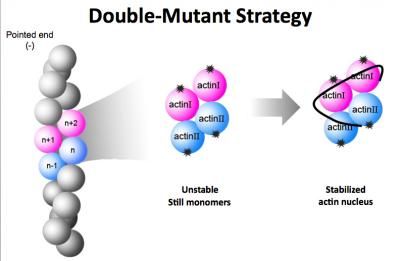

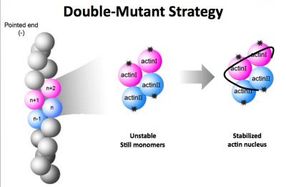

To decipher the structure of the F-actin nucleus, researchers used a dual-mutant strategy. They created two mutant versions of actin monomers that could bind together to form a nucleus but could not bind with additional monomers to form the F-actin polymer chain.

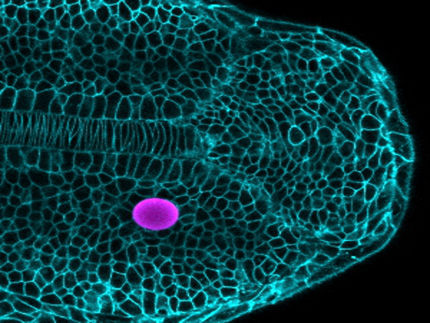

J. Ma/Rice University

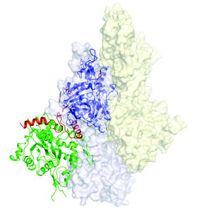

This image shows the 3-D structure of the F-actin nucleus. The core of the two actin monomers contained in the nucleus are depicted in green and purple.

X. Chen/BCM

The biological "freeze-frame" shows the initial step in the formation of actin, a sturdy strand-like filament that is vital for humans. Actin filaments help cells maintain their shape. The filaments, which are called F-actin, also play key roles in muscle contraction, cell division and other critical processes.

"One of the major distinctions between cancerous cells and healthy cells is their shape," said study co-author Jianpeng Ma, professor of bioengineering at Rice and the Lodwick T. Bolin Professor of Biochemistry at BCM. "There is a correlation between healthy shape and well-regulated cell growth, and cancer cells are often ugly and ill-shaped compared to healthy cells."

F-actin was discovered in 1887, but despite the more than 18,000 actin-related studies in scientific literature, biologists have struggled to unlock some of its secrets. For example, F-actin is a polymer made of many smaller proteins called monomers. These building blocks, which are called G-actin, self-assemble end to end to form F-actin. But the self-assembly process is so efficient that scientists have been unable to see what happens when the first two or three monomers come together to form the nucleus of a filament. The F-actin filaments inside cells are constantly being built, torn apart and rebuilt.

"Nucleation is critical for this continual building and rebuilding," said BCM biochemist and study co-author Qinghua Wang. "For healthy cells, nucleation is the starting place for robust shape. For unhealthy cells, like cancer, nucleation processes may play a crucial role in unregulated growth. That's one reason we want to better understand nucleation."

In 2008, Ma and Wang asked Xiaorui Chen, a graduate student in BCM's Structural and Computational Biology and Molecular Biophysics program, to undertake the task of using x-ray crystallography to determine the structure of the actin nucleus. Her initial attempts failed, but the team finally hit upon the winning idea of creating two mutant versions of G-actin that could nucleate but not polymerize.

Native G-actin binds with one neighbor on top and one on bottom, and this top-bottom, end-to-end binding pattern is the key to forming long F-actin polymers. To foster nucleation without polymerization, Chen created two mutant versions of G-actin. One mutant could bind normally on top but not on bottom, and the other could bind normally on bottom but not on top.

"This dual-mutant strategy was the key," said Chen, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at BCM. "After that, we had to overcome problems related to forming and growing the crystal samples needed for crystallography."

Chen used a two-stage process to prepare the crystals. She first used high levels of super-saturation to spur initial crystal formation and then used a process called seeding to transfer the newly formed crystals to another medium where they could grow large enough for examination.

Once the crystals were prepared, they were analyzed with x-ray diffraction, which revealed the atomic arrangement of each atom in the nucleated, dual-mutant pair. "We believe this dual-mutant arrangement reveals the most critical contacts involved in nucleation," Ma said. "For the first time, we are able to see how actin nucleation begins."