Researchers identify genetic sequence that helps to coordinate synthesis of DNA-packaging proteins

Every time a cell divides it makes a carbon copy of crucial ingredients, including the histone proteins that are responsible for spooling yards of DNA into tight little coils. When these spool-like proteins aren't made correctly, it can result in the genomic instability characteristic of most birth defects and cancers.

Seven years ago, Dr. Joe Gall of the Carnegie Institute in Baltimore, Md. and coworkers noticed an aggregation of molecules along a a block of genome that codes for the critical histones, but they had no idea how this aggregate or "histone locus body" was formed.

Now, research conducted in fruit flies at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine has pinpointed a specific DNA sequence that both triggers the formation of this "histone locus body" and turns on all the histone genes in the entire block.

The finding, published in the journal Developmental Cell, provides a model for the coordinated synthesis of histones needed for assembly into chromatin, a process critical to keeping chromosomes intact and passing genetic information from generation to generation.

"Our study has uncovered a new relationship between nuclear architecture and gene activity," said senior study author Bob Duronio, PhD, professor of biology and genetics at UNC. "In order to make chromosomes properly, you need to make these histone building blocks at the right time and in the right amount. We found that the cell has evolved this complex architecture to do that properly, and that involves an interface between the assembly of various components and the turning on of a number of genes."

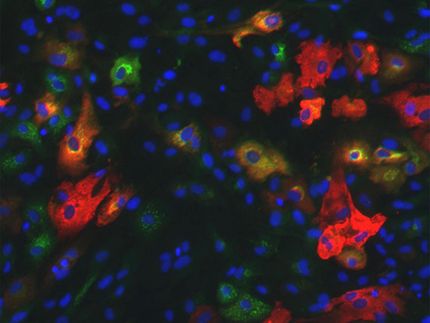

In the fruit fly, as in the human, the five different histone genes exist in one long chunk of the genome. The "histone locus" in flies contains 100 copies of each of the five genes, encompassing approximately 500,000 nucleotides of A's, C's, T's and G's. The proteins required for making the histone message – a process that must happen every time a new strand of DNA is copied – come together at this "histone locus" to form the "histone locus body."

Duronio and co-senior study author William Marzluff, PhD, Kenan Distinguished Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics, wanted to figure out how these factors knew to meet at the histone locus.

They inserted different combinations of the five histone genes into another site of the genome, and looked to see which combinations recruited a new histone locus body. The researchers found that combinations that contained a specific 300 nucleotide sequence – the region between the H3 and H4 histone genes – formed a histone locus body. In contrast, combinations of genes that lacked this sequence did not form the body. They went on to show that this sequence turned on not only the H3 and H4 genes in its direct vicinity, but also other histone genes in the block.

Though the research was conducted entirely in fruit flies, it may lend insight into mechanisms that keep the genome from becoming unstable – and causing early death or illness -- in higher organisms.

"Humans and flies have these very same histone genes. They have the same proteins in the histone locus body. So understanding precisely how this works in flies will help us understand cell division in humans," said Marzluff.

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.