Transistor in the fly antenna

Insect odorant receptors regulate their own sensitivity

Advertisement

Highly developed antennae containing different types of olfactory receptors allow insects to use minute amounts of odors for orientation towards resources like food, oviposition sites or mates. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany, have now used mutant flies and for the first time provided experimental proof that the extremely sensitive olfactory system of fruit flies − they are able to detect a few thousand odor molecules per milliliter of air, whereas humans need hundreds of millions − is based on self-regulation of odorant receptors. Even fewer molecules below the response threshold are sufficient to amplify the sensitivity of the receptors, and binding of molecules shortly afterwards triggers the opening of an ion channel that controls the fly’s reaction and flight behavior. This means that a below threshold odor stimulation increases the sensitivity of the receptor, and if a second odor pulse arrives within a certain time span, a neural response will be elicited.

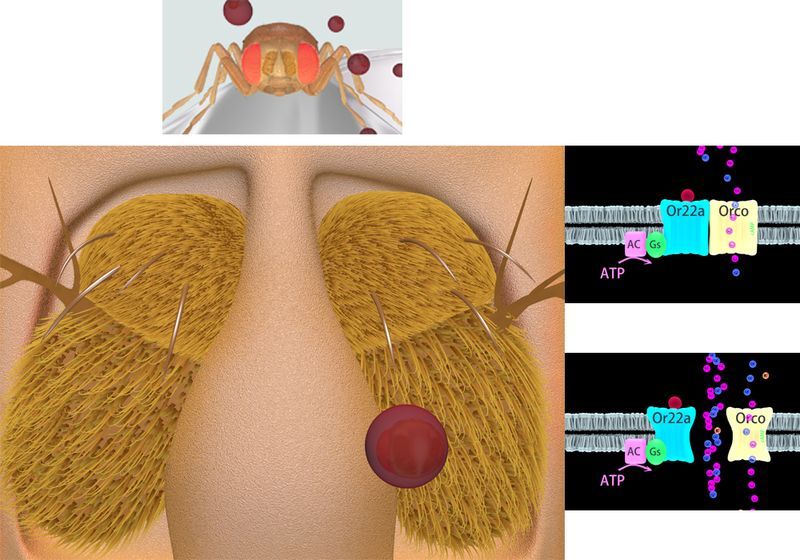

The antennae of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, shown schematically in dark yellow. Dark red: odor molecules. Right: The odorant receptors studied are protein dimers consisting of the odorant receptor Or22a and the co-receptor Orco; they mediate very sensitive responses to odor molecules. Above: State of sensitization − weak ion flow caused by cAMP; below: signals are “switched through” in the receptor system resulting in opening of the ion channel and electric signal transduction.

Graphik: Dieter Wicher, Max-Planck-Institut für chemische Ökologie. Filmische Animation: Moves Like Nature, Kimberly Falk

A sensitive sense of smell is vital

It is amazing how many fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) find their way to a rotting apple. It is known that insects are able to detect the slightest concentrations of odor molecules, especially pheromones, but also “food signals”.

Dieter Wicher, Shannon Olsson, Bill Hansson and their colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology were looking for answers to the question why insects can trace odor molecules so easily and at such low concentrations in comparison to other animals. They focused their attention on odorant receptor proteins in the antenna, the insects’ nose. These insect proteins are pretty young from an evolutionary perspective and their molecular constituents may be the basis for the insects’ highly sensitive sense of smell.

Receptor system Or22a-Orco

Insect odorant receptors form a receptor system that consists of the actual receptor protein and an ion channel. After binding of an odor molecule, receptor protein and ion channel trigger the neural electrical response. This mechanism was recently described in the receptor system Or22a-Orco in Nature. Apart from functioning as so-called ionotropic receptors, which enable ion flow through membranes after binding of odor molecules, odorant receptors also elicit intracellular signals. These stimulate the formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cyclic AMP or cAMP), which activates an ion flow through the co-receptor Orco. The role and relevance of this weak and slow electrical current, however, was until now unclear.

Drosophila mutant Orco mut

Merid N. Getahun, a PhD student from Ethiopia, and his colleagues have conducted numerous experiments on Drosophila olfactory neurons. They injected tiny amounts of compounds that stimulate, inhibit or imitate cAMP formation directly into the sensory hairs housing olfactory sensory neurons on the fly antenna. The researchers tested the flies’ responses to ethyl butyrate, which has a fruity odor similar to pineapple, and measured activity in the sensory neurons by using glass microelectrodes. As a control, they used genetically modified fruit flies where the co-receptor Orco had been inactivated. “The fact that these mutants are no more able to respond to cAMP or the inhibition/activation of the involved key enzymes, such as protein kinase C and phospholipase C, shows that the highly sensitive olfactory system in insects is regulated intracellularly by their own odorant receptors,” says Dieter Wicher, the leader of the research group. The combination of odorant receptor and co-receptor Orco can be compared to a transistor, Wicher continues: A weak basic current is sufficient to release the main electric current that activates the neuron. The process can also be seen as a short-term memory situated in the insect nose. A very weak stimulus does not elicit a response when it first occurs, but if it reoccurs within a certain time span it will release the electrical response according to the principle “one time is no time, but two is a bunch.”