Protein origami: Quick folders are the best

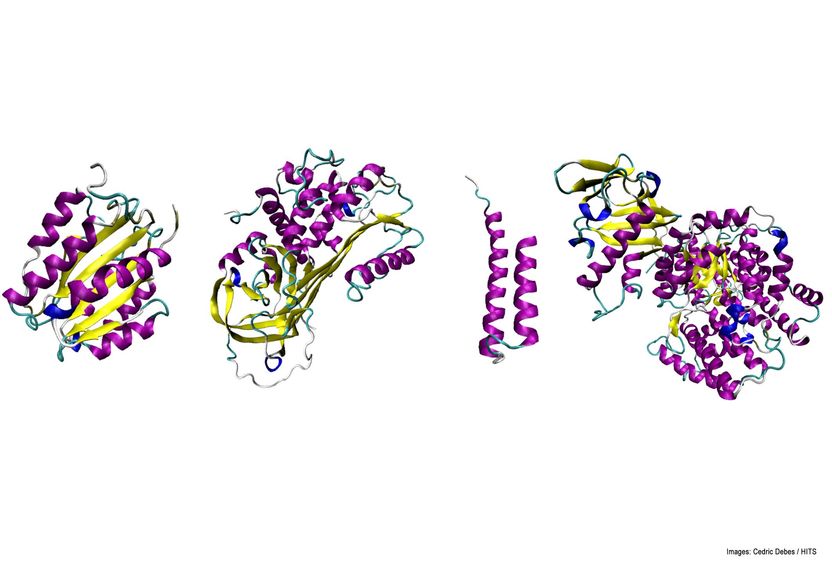

The evolutionary history of proteins shows that protein folding is an important factor. Especially the speed of protein folding plays a key role. This was the result of a computer analysis carried out by researchers at the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies (HITS) and the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. For almost four billions of years, there has been a trend towards faster folding. “The reason might be that this makes proteins less susceptible to clumping, and that they can carry out their tasks faster,” says Dr. Frauke Gräter (HITS) who led the analysis. Proteins are elementary building blocks of life. They often perform vital functions. In order to become active, proteins have to fold into three-dimensional structures. Misfolding of proteins leads to diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Creutzfeld-Jakob. So which strategies did nature develop over the course of evolution to improve protein folding?

Nature has come up with numerous forms of protein folding. Most of these forms emerged after the biological Big Bang, which took place approximately 1.5 billion years ago. According to the study, folding speed belongs to the important factors of this diversification.

Cedric Debes / HITS

To examine this question, the chemist Dr. Frauke Gräter (Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies) looked far back into the history of the Earth. Together with her colleague Prof. Gustavo Caetano-Anolles at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, she used computer analyses to examine the folding speed of all currently known proteins. The researchers have seen the following trend: For most of protein evolution, the folding speed increased, from archaea to multicellular organisms. However, 1.5 billion years ago, more complex structures emerged and caused a biological ‘Big Bang’. This has led to the development of slower-folding protein structures. Remarkably, the tendency towards higher speed in protein origami overall dominated, regardless of the length of amino acid chains constituting the proteins.

“The reason for higher folding speed might be that this makes proteins less susceptible to aggregation, so that they can carry out their tasks faster,” says Dr. Frauke Gräter, head of the Molecular Biomechanics research group at HITS.

Genetics and biophysics for large volumes of data

In their work, the researchers used an interdisciplinary approach combining genetics and biophysics. “It is the first analysis to combine all known protein structures and genomes with folding rates as a physical parameter,” says Dr. Gräter.

The analysis of 92,000 proteins and 989 genomes can only be tackled with computational methods. The group of Gustavo Caetano-Anolles, head of the Evolutionary Bioinformatics Laboratory at Urbana-Champaign, had originally classified most structurally known proteins from the Protein Database (PDB) according to age. For this study, Minglei Wang in his laboratory identified protein sequences in the genomes, which had the same folding structure as the known proteins. He then applied an algorithm to compare them to each other on a time scale. In this way, it is possible to determine which proteins became part of which organism and when. After that, Cedric Debes, a member of Dr. Gräter’s group, applied a mathematical model to predict the folding rate of proteins. The individual folding steps differ in speed and can take from nanoseconds to minutes. No microscope or laser would be able to capture these different time scales for so many proteins. A computer simulation calculating all folding structures in all proteins would take centuries to run on a mainframe computer. This is why the researchers worked with a less data-intensive method. They calculated the folding speed of the single proteins using structures that have been previously determined in experiments: A protein always folds at the same points. If these points are far apart from each other, it takes longer to fold than if they lie close to each other. With the so-called Size-Modified Contact Order (SMCO), it is possible to predict how fast these points will meet and thus how fast the protein will fold, regardless of its length.

“Our results show that in the beginning there were proteins which could not fold very well,” Dr. Gräter summarizes. “Over time, nature improved protein folding so that eventually, more complex structures such as the many specialized proteins of humans were able to develop.”

Shorter and faster for evolution

Amino acid chains, which make up proteins, also became shorter over the course of evolution. This was another factor contributing to the increase in folding speed, as has been shown in the study. “Since eukaryotes, i.e. organisms with a cell nucleus, emerged, protein folding became somewhat less crucial,” says Frauke Gräter. Since then, nature has developed a complex machinery to prevent and repair misfolded proteins. One example are the so-called chaperones. “It seems as if nature would accept a certain level of disorder in order to develop structures which could not have evolved otherwise.”

The number of known genomes and protein structures is continually increasing, thus expanding the data bases for further computer analyses of protein evolution. Frauke Gräter says “With future analyses of protein evolution, it might be possible for us to answer the related question whether proteins became more stable or more flexible over their billion-year-long history of evolution.”