Hearing loss prevention drugs closer to reality thanks to new testing method from the University of Florida

A new way to test anti-hearing-loss drugs in people could help land those medicines on pharmacy shelves sooner. University of Florida researchers have figured out the longstanding problem of how to safely create temporary, reversible hearing loss in order to see how well the drugs work. The findings are described in the Ear & Hearing.

“There’s a real need for drug solutions to hearing loss,” said lead investigator Colleen Le Prell, Ph.D., an associate professor in the department of speech, language, and hearing sciences at the UF College of Public Health and Health Professions. “Right now the only options for protecting against noise-induced hearing loss are to turn down what you’re listening to, walk away from it or wear ear plugs, and those options may not be practical for everyone, particularly for those in the military who need to be able to hear threats.”

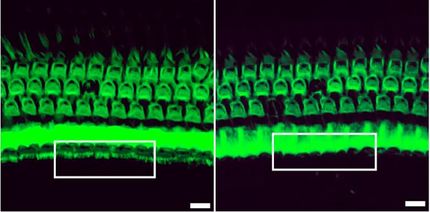

About 26 million American adults have noise-induced hearing loss, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Prevention is key because damage to hearing-related hair cells in the inner ear by loud noise is irreversible. Though hearing aids can help amplify sound and implanted devices can restore some sensation of sound for those with more profound hearing loss, they do not restore normal hearing. Thus, researchers are trying to find drugs that prevent hearing damage in the first place.

Although prototype drugs have prevented noise-induced hearing loss in laboratory animals, it has been hard to know whether the same protection is possible in humans, largely because researchers lacked an effective method for the needed tests. Those tests are now achievable because of the UF efforts. The work brings scientists closer to the development of drugs that could help protect people at risk of hearing damage — from rock concert goers to factory workers and military personnel who are routinely exposed to noise as they work.

Le Prell’s model is the first to use controlled music levels to reliably cause low-level, temporary hearing loss in human participants. Other studies have used beeps or tones, user-selected music levels, or music exposures that don’t result in temporary hearing loss. Three monitoring boards ensured that studies of the UF model met national safety standards for research in humans. Co-investigator Patrick Antonelli, M.D., the George T. Singleton Professor and chair of the UF department of otolaryngology, provided onsite supervision of study participant safety, and collaborators at the University of Michigan and Southern Illinois University were involved in study design and safety discussions.

To induce temporary hearing loss, study participants listened to rock or pop music on a digital music player via headphones for four hours at sound levels ranging from 93 decibels — the noise level of a power lawn mower — to 102 decibels, the noise of a jackhammer. Each participant got a hearing test four times, 15 minutes to three-and-a-quarter hours after his or her listening session, as well as follow-up tests one day and one week later. Fifteen minutes after the music stopped, those who listened to the highest music levels had lost just a small amount of hearing — six decibels, on average. Hearing returned to normal within three hours.

Le Prell’s group will use this testing model in two first-of-a-kind clinical trials of therapeutics designed to determine if noise-induced hearing loss can be prevented in humans. The first study uses a dietary supplement called Soundbites, manufactured by Hearing Health Science, a University of Michigan bioscience spinoff company. Soundbites contains the vitamin A precursor beta carotene, vitamins C and E and the mineral magnesium. This antioxidant formula, the patent for which Le Prell shares, has prevented temporary and permanent hearing loss in laboratory animals.

In the other ongoing study, participants take a drug called SPI-1005 produced by Sound Pharmaceuticals Inc. The test capsule contains a new molecule called ebselen that mimics a protective inner ear protein.

The Food and Drug Administration will monitor the studies to ensure openness, analytical rigor and participant safety as the researchers try to get badly needed drugs onto the market.