Genetic admixture in southern Africa

Ancient Khoisan lineages survive in contemporary Bantu groups

An international team of researchers from the MPI for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig and the CNRS in Lyon have investigated the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA of 500 individuals from southern Africa speaking different Khoisan and Bantu languages. Their results demonstrate that Khoisan foragers were genetically more diverse than previously known. Divergent mtDNA lineages from indigenous Khoisan groups were incorporated into the genepool of the immigrating Bantu-speaking agriculturalists through admixture, and have thus survived until the present day, although the Khoisan-speaking source populations themselves have become extinct.

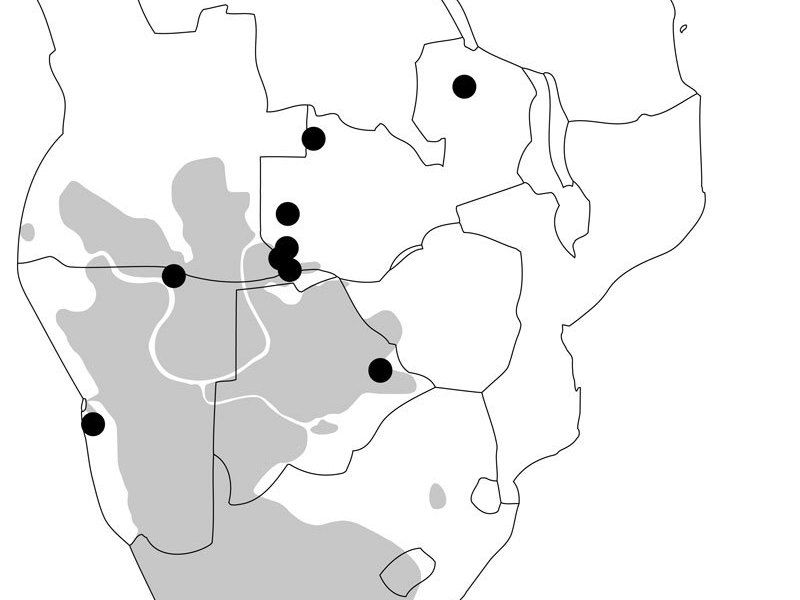

Historically know distribution of Khoisan (grey area) and divergent Khoisan mitochondrial DNA lineages (black dots).

© MPI f. evolutionäre Anthropologie

The hunter-gatherer and pastoralist peoples of southern Africa who speak indigenous non-Bantu languages called Khoisan have intrigued researchers for a long time because their languages contain highly unusual click consonants and because they harbour some of the most deep-rooting genetic lineages in modern humans. Based on archaeological finds it is assumed that some of these Khoisan peoples are the descendants of indigenous Late Stone Age foragers, while peoples speaking Bantu languages immigrated into this area only 2,000-1,200 years ago.

From historical documents the Khoisan peoples were known predominantly in the area of what is now South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, southern Angola and bordering areas of southwestern Zambia. Genetic research has now found evidence that Khoisan peoples must have been settled further to the north in Zambia as well – but that these northern groups of Khoisan were genetically quite distinct from the Khoisan peoples known nowadays. By sequencing the complete mitochondrial genomes – which are inherited only in the maternal line - of 500 individuals speaking different Khoisan and Bantu languages from Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Angola, a team of researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig and the CNRS in Lyon, in collaboration with researchers from the University of Botswana and the University of Porto, have discovered divergent Khoisan mitochondrial DNA lineages in some Bantu-speaking groups predominantly from Zambia. These divergent lineages are nearly exclusively found in individuals speaking Bantu languages and are practically absent from any of the peoples speaking Khoisan languages.

“Our analyses indicate that the best explanation for our findings is that the Bantu-speaking immigrants married resident Khoisan women when they first came to southern Africa, thus incorporating these divergent lineages into their maternal genepool. The Khoisan peoples with whom they came into contact probably disappeared later on, since we do not find these divergent Khoisan lineages in any of the known Khoisan peoples,” says Chiara Barbieri from the MPI for Evolutionary Anthropology and lead author of the study. “This is a really important finding, because it demonstrates that we might be able to learn more about the peoples who inhabited sub-Saharan Africa before the Iron Age spread of Bantu-speaking agriculturalists by studying relic lineages that were taken up by the agriculturalists through intermarriage with indigenous peoples,” adds Brigitte Pakendorf from the CNRS lab Dynamique du Langage in Lyon, who coordinated the study.

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.