Cancer Research Yields Unexpected New Way to Produce Nylon

In their quest for a cancer cure, researchers at the Duke Cancer Institute made a serendipitous discovery - a molecule necessary for cheaper and greener ways to produce nylon. The finding, described in Nature Chemical Biology, arose from an intriguing notion that some of the genetic and chemical changes in cancer tumors might be harnessed for beneficial uses.

“In our lab, we study genetic changes that cause healthy tissues to go bad and grow into tumors. The goal of this research is to understand how the tumors develop in order to design better treatments,” said Zachary J. Reitman, Ph.D., an associate in research at Duke and lead author of the study. “As it turns out, a bit of information we learned in that process paves the way for a better method to produce nylon.”

Nylon is a ubiquitous material, used in carpeting, upholstery, auto parts, apparel and other products. A key component for its production is adipic acid, which is one of the most widely used chemicals in the world. Currently, adipic acid is produced from fossil fuel, and the pollution released from the refinement process is a leading contributor to global warming.

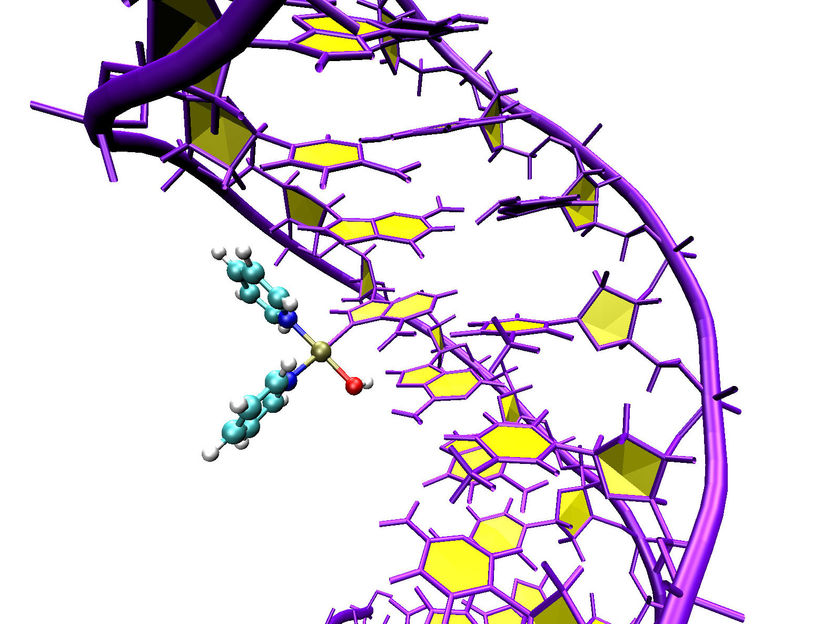

Reitman said he and colleagues delved into the adipic acid problem based on similarities between cancer research techniques and biochemical engineering. Both fields rely on enzymes, which are molecules that convert one small chemical to another. Enzymes play a major role in both healthy tissues and in tumors, but they are also used to convert organic matter into synthetic materials such as adipic acid.

One of the most promising approaches being studied today for environmentally friendly adipic acid production uses a series of enzymes as an assembly line to convert cheap sugars into adipic acid. However, one critical enzyme in the series, called a 2-hydroxyadipate dehydrogenase, has never been produced, leaving a missing link in the assembly line.

This is where the cancer research comes in. In 2008 and 2009, Duke researchers, including Hai Yan, M.D., PhD., identified a genetic mutation in glioblastomas and other brain tumors that alters the function of an enzyme known as an isocitrate dehydrogenase.

Reitman and colleagues had a hunch that the genetic mutation seen in cancer might trigger a similar functional change to a closely related enzyme found in yeast and bacteria (homoisocitrate dehydrogenase), which would create the elusive 2-hydroxyadipate dehydrogenase necessary for “green” adipic acid production.

They were right. The functional mutation observed in cancer could be constructively applied to other closely related enzymes, creating a beneficial outcome – in this case the missing link that could enable adipic acid production from cheap sugars. The next step will be to scale up the overall adipic acid production process, which remains a considerable undertaking.

“It’s exciting that sequencing cancer genomes can help us to discover new enzyme activities,” Reitman said. “Even genetic changes that occur in only a few patients could reveal useful new enzyme functions that were not obvious before.”

Yan, a professor in the Department of Pathology and senior author of the study, said the research demonstrates how an investment in medical research can be applied broadly to solve other significant issues of the day.

“This is the result of a cancer researcher thinking outside the box to produce a new enzyme and create a precursor for nylon production,” Yan said. “Not only is this discovery exciting, it reaffirms the commitment we should be making to science and to encouraging young people to pursue science.”

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.