Protein critical to gut lining repair

Scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a protein essential to repairing the intestine's inner lining. That lining is among the body's busiest highways, trod not only by the food we ingest but also by trillions of microorganisms that aid digestion. Because the intestine plays key roles in absorbing nutrients and containing the microbes, any damage must be fixed promptly.

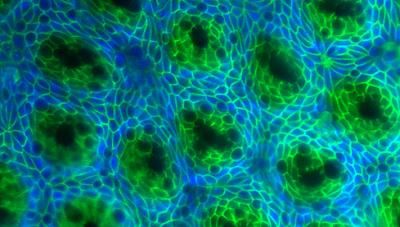

Scientists have identified a protein that is critical to repairing glands in the intestine’s inner lining. The glands appear as dark green spots above and are rebuilt every two to four weeks as the inner lining of the gut is continually renewed.

Hiroyuki Miyoshi

The researchers report in Science Express that a protein called Wnt5a is essential for reconstructing glands in the intestinal lining. The glands, called crypts of Lieberkühn, contain stem cells that continually pump out other cells that renew the gut lining, which is replaced every two to four weeks. The crypts look like dimples in the gut lining and are vulnerable to damage and loss from infection and inflammation.

"For example, inflammatory bowel disease can destroy huge stretches of the lining, including the crypts," says senior author Thaddeus Stappenbeck, MD, PhD, associate professor of pathology and immunology. "If crypts can't be repaired as the lining is rebuilt, their absence would place substantial stresses on crypts in healthy portions of the gut. So it's important to better understand how the crypts are replaced."

In the new study, Stappenbeck and his colleagues showed that when crypts are lost to injury in mice, the nearest surviving crypts expand into the damaged area and create an array of channels. These wound channels, which contain rapidly dividing stem cells, eventually subdivide into new crypts.

Stappenbeck found that cells that line the outer wall of the gut migrate to sites of damage within the inner lining to provide Wnt5a, a signaling molecule that stops stem cells from dividing. This shutdown triggers the formation of dimples in the wound channels that become new crypts.

Because mice that lack the Wnt5a gene aren't viable, co-author Terry Yamaguchi, PhD, of the National Cancer Institute, bred mice in which scientists could selectively turn off the gene after the mice became adults. When the gut lining was injured and Wnt5a was disabled, the wound channels formed but failed to divide into crypts.

To further confirm the link between the gene and crypt repair, Hiroyuki Miyoshi, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Stappenbeck's laboratory, devised a robust method for growing gut stem cells in test tubes. When he applied Wnt5a to the stem cells, they stopped dividing, proving that the protein was the critical ingredient for initiating crypt formation.

The scientists also showed that Wnt5a activated a signaling pathway in the stem cells that is known to stop cell proliferation. Stappenbeck, who also is an associate professor of developmental biology, is now planning additional studies of Wnt5a, including investigations of whether the protein plays similar roles elsewhere in the body.

Original publication

Miyoshi H, Ajima R, Luo C T-Y, Yamaguchi TP, Stappenbeck TS; "Wnt5a potentiates TGF-beta signaling to promote colonic crypt regeneration after tissue injury."; Science Express, 2012.

Most read news

Original publication

Miyoshi H, Ajima R, Luo C T-Y, Yamaguchi TP, Stappenbeck TS; "Wnt5a potentiates TGF-beta signaling to promote colonic crypt regeneration after tissue injury."; Science Express, 2012.

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

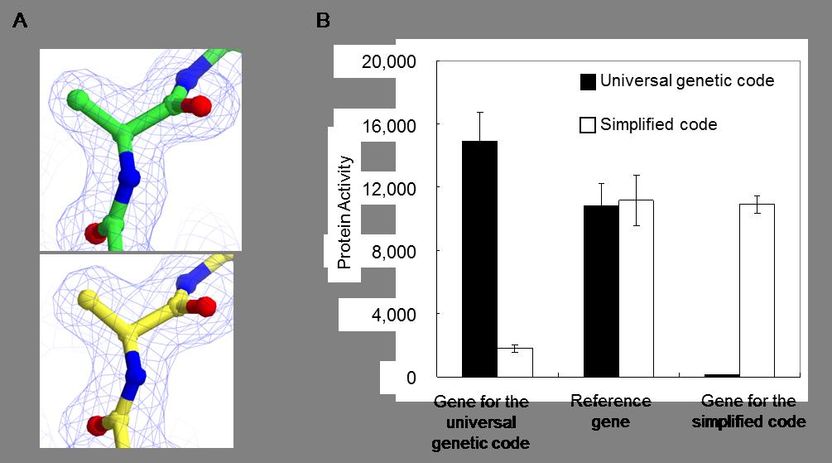

Tokyo Institute of Technology research: Simplifying genetic codes to look back in time - Tokyo Institute of Technology researchers show simpler versions of the universal genetic code can still function in protein synthesis

Cresset Announces New International Sales Team

A cancer shredder - A new compound for treating cancer: It destroys a protein that triggers its development

Celonic Acquires Glycotope’s Bio-manufacturing Facility