A double ring ceremony prepares telomerase RNA to wed its protein partner

Few molecules are more interesting than DNA — except of course RNA. After two decades of research, that "other macromolecule" is no longer considered a mere messenger between glamorous DNA and protein-synthesizing machines. We now know that RNA has been leading a secret life, regulating gene expression and partnering with proteins to form catalytic ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes.

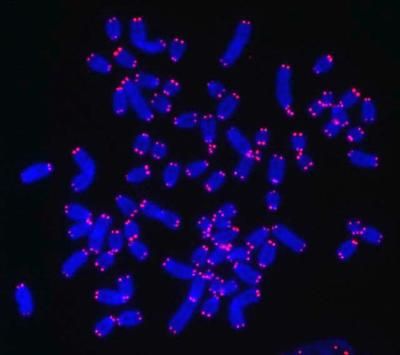

Proper processing of the RNA component of telomerase, the enzyme that maintains the ends of chromosomes (shown in red), is essential for the formation of active telomerase complexes.

Courtesy of Dr. Peter Baumann, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

One of those RNPs is telomerase, an enzyme that maintains chromosome integrity. In Nature, researchers at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research report how the RNA TER1, a component of telomerase, is sculpted to favor interaction with its protein partner. Two ring-like proteins sequentially slip onto unprocessed TER1 RNA and hold it while it is clipped to the optimum size, folded, and capped.

That processing is essential: without it TER1 could not engage its protein partner to form the active telomerase RNP. The finding not only deepens our understanding of RNA biochemistry but also suggests novel pharmaceutical approaches to cancer and diseases of aging.

"Cancer cells are exquisitely dependent on telomerase," says Stowers associate investigator and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Scientist Peter Baumann, Ph.D., the study's senior author. "Drugs inhibiting telomerase could be a new class of cancer chemotherapeutics with far fewer side effects than drugs in use." Currently, biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies are actively seeking clinically useful telomerase inhibitors.

Most RNA strands — including the intermediary or "messenger" RNAs — undergo splicing, analogous to editing a film. The universal snipper is a humongous complex called the spliceosome, which usually touches down on an RNA strand, makes two cuts, and then pastes the new ends together. But in a 2008 Nature study, the Baumann group reported a surprising finding. "We showed that the spliceosome acts to process TER1," he says. "But instead of cutting twice and pasting, it made a single cut and stopped."

To determine what restrained the spliceosome from making a second cut, Baumann's group analyzed TER1 RNA in the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. They found that two protein complexes called Sm and Lsm latched onto TER1 RNA in a mutually exclusive fashion as the RNA matures. Interestingly, Lsm-bound TER1 RNA showed the most efficient telomerase activity, hinting that the Sm ring slips on first.

For further analysis they enlisted the aid of Stowers' assistant investigator Marco Blanchette, Ph.D., an RNA splicing expert. The team confirmed that indeed Sm bound immature TER1 RNA, prompting the incoming spliceosome to snip off everything to its "right". Once that cut was made, Sm appeared to promote formation of a protective tri-methylated "cap" on the "left" end of the TER1 transcript, thus stabilizing it. At that point the Sm ring slipped off and was replaced by Lsm, facilitating recruitment of TER1's catalytic protein partner.

This work shows that the marriage of RNA and protein telomerase partners requires a two-step ritual attended first by Sm and then by Lsm proteins. The presence of Lsm in preparations of the active enzyme also suggests that it lingers after the ceremony to protect mature Ter1 RNA from RNA-damaging enzymes.

Determining what the evolutionarily conserved Sm and Lsm proteins do is a significant contribution to RNA biology, says Wen Tang, a graduate student in the Baumann lab who led the study. "People discovered these proteins 20 years ago and knew they were essential for RNA processing," says Tang. "Right now we don't know whether Sm and Lsm participate in processing of telomerase in human cells. Other members of the lab are looking into that."

Understanding how telomerase works in human cells is vital because of its connection to seemingly unrelated diseases. Not only because cancer cells depend on its activity, but in a fascinating "converse", mutations that inactivate telomerase are seen in a degenerative condition called dyskeratosis congenital (DKC), in which patients show signs of premature aging in some organs.

"People have looked for mutations in telomerase components in individuals with DKC and found them in only about half of those patients," says Wen Tang. "This work identifies novel telomerase components that likely affect normal enzyme function." Those components could provide novel targets potentially useful to diagnose or treat DKC.

Baumann agrees that knowing how to tinker with TER1 biogenesis has therapeutic potential in several contexts. But he is equally happy that the new work adds to scientists' appreciation of RNA complexity. "This paper fills in the blanks between transcription of the TER1 RNA subunit and formation of an active telomerase complex," he says. "We also hope it provides a more complete picture of TER1 biogenesis in future textbooks."