Bone marrow transplant arrests symptoms in model of Rett syndrome

Results emphasize immune component of autism spectrum disorder

Advertisement

A paper published in Nature describes the results of using bone marrow transplant (BMT) to replace faulty immune system cells in models of Rett Syndrome. The procedure arrested many severe symptoms of the childhood disorder, including abnormal breathing and movement, and significantly extended the lifespan of Rett mouse models. Exploring the function of microglia deficient in methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (Mecp2), the protein encoded by the "Rett gene," principal investigator Jonathan Kipnis, Ph.D. and his team at the University of Virginia School of Medicine uncovered a completely novel approach to this devastating neurological syndrome. The work was funded by the Rett Syndrome Research Trust and the Rett Syndrome Research Trust UK.

Pictured are Jonathan Kipnis Ph.D., Jim Cronk, Noël Derecki, Ph.D. of the University of Virginia.

Jonathan Kipnis, Ph.D.

Rett Syndrome, the most physically disabling of the autism spectrum disorders, is caused by random mutations in the gene MECP2. Predominantly affecting girls, symptoms usually manifest between 6 and 18 months of age, when a frightening regression begins. Children lose acquired language skills and functional hand use; movement deteriorates as other Rett symptoms appear. These may include disordered breathing, Parkinsonian tremors, severe anxiety, seizures, digestive and circulatory problems and a range of autonomic nervous system and orthopedic abnormalities Although most children survive to adulthood, many are wheelchair-bound, rely on feeding tubes, are unable to communicate and require total, lifelong care.

Kipnis was drawn to Rett Syndrome from his perspective as a neuroimmunologist. "What began as intellectual curiosity," he explains, "has become an intense personal commitment to studying the correlation between neurological function and the immune system in Rett Syndrome. The impact of BMT on so many different symptoms has triggered a flood of experiments we are now pursuing at full speed."

The brain is largely comprised of several types of glial cells, which have diverse and complex functions that include sustaining a healthy environment for neuronal growth and maintenance. Microglia are small glial cells that participate in the brain's immune response. One of their roles is to clean up normal cellular debris in the brain through the process of phagocytosis. Kipnis and his team discovered that when microglia lack properly functioning Mecp2, they are unable to perform this crucial duty efficiently. Because microglia are derived from immune progenitor cells, it is possible to replace them via a bone marrow transplant.

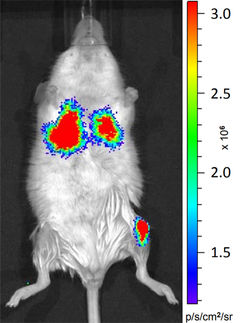

First author Noël Derecki and his colleagues began their work with male Rett mouse models, which lack any Mecp2. These Mecp2-null mice mimic the human disorder, with neurological symptoms beginning to appear at about 4 weeks of age and an approximate life expectancy of only 8 weeks. Radiation treatment was administered at 4 weeks, followed by a bone marrow transplant from normal (wild-type) mice. As engraftment - the migration and repopulation of new microglia - took place, the Rett mice began to grow instead of fail. Body and brain sizes approached those of wild-type mice, gait improved and mobility increased significantly. There were no signs of the severe tremors seen in untreated mice. Apneas and other breathing irregularities were markedly diminished. The oldest of these mice is now almost a year. Work with female Rett mouse models at more advanced stages of disease is currently underway.