Scientists advance understanding of Listeria

Listeria is an opportunistic pathogen that causes brain infection, blood poisoning, abortion and death for about 500 Americans and a number of farm animals each year. But while its harmful strains can be more lethal than Salmonella, it exists in benign species and strains as well.

By finding out why some forms are fatal and others are not, Cornell researchers are developing more effective ways to detect and prevent food-borne illness.

When it comes to predicting whether strains of the bacterium will be harmful, Martin Wiedmann, associate professor of food science, has found that it is necessary to test for the presence of several genes, rather than just one.

Even among Listeria monocytogenes, which causes the vast majority of human disease cases, his team identified a strain that lacked one gene linked to the ability to cause disease.

In a paper published in BMC Genomics, Wiedmann also describes how the genus Listeria has evolved over the past 47 million years.

Unlike some other bacteria, Listeria strains actually appear to have become less virulent over time. While their common ancestor carried all genes needed to cause disease, many of the strains that emerged did not, and only two of the six Listeria species Wiedmann studied were found to have all the genes likely needed to cause human disease.

This may be because it is in the best interest of the bacteria that their hosts are kept alive, he said.

Originating in soil and often traveling to animals through plant materials, Listeria bacteria thrive inside mammalian bodies, where there is limited competition for food. They can invade human cells and are able to move from one cell to the next, avoiding the antibodies we have floating around our bodies, Wiedmann said.

Listeria monocytogenes causes listeriosis, a rare but potentially lethal food-borne infection, with symptoms similar to meningitis. About 20 percent of people diagnosed with listeriosis die, compared to less than 1 percent of those inflicted by Salmonella.

Listeria has been found in animal silage, raw meats and vegetables, unpasteurized milk and different processed foods. Pasteurization and sufficient cooking typically kill Listeria, but contamination can occur after heating and before packaging, so extensive sanitation is required at processing plants, Wiedmann said.

"It has a canny ability to survive very, very well," Wiedmann said. "In one case, we found a strain that had survived in a processing plant for 12 years."

Wiedmann's team has helped control previous Listeria outbreaks by tracing the origin of contamination, thanks in part to a Web-based pathogen tracker database they also developed. He also recently identified a unique strain of Listeria monocytogenes that was responsible for an outbreak among dairy cattle, with his findings detailed in a paper to be published in the Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation.

"We create the basic knowledge, which industry can then develop into practical applications," Wiedmann said.

Industry has already taken notice. Study collaborator Life Technologies Corp. is planning to use the information Wiedmann collected to develop assays that specifically detect pathogenic Listeria strains, according to bioinformatics scientist Craig Cummings.

His company developed The SOLiD System, an advanced, "next generation" sequencing instrument used in the study.

"This system allows us to discover the differences between large sets of bacterial strains in a relatively fast and affordable way," Cummings said.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Amyotrophic_lateral_sclerosis

Ferriman-Gallwey_score

GE Healthcare completes acquisition of Whatman plc

Osmotic_demyelination_syndrome

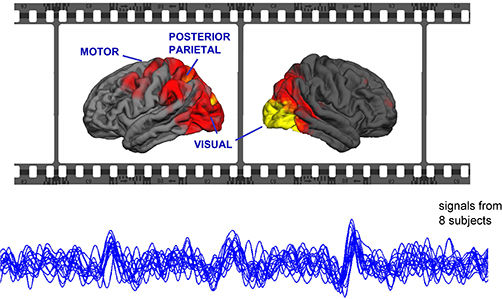

Movies synchronize brains - When we watch a movie, our brains react to it immediately in a way similar to other people's brains.

Innovative genetic and cellular techniques help identify multiple disease targets

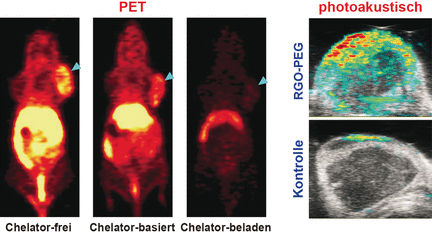

Direct radiolabeling of nanomaterials

Research will speed tracing bacteria behind salmonella outbreaks

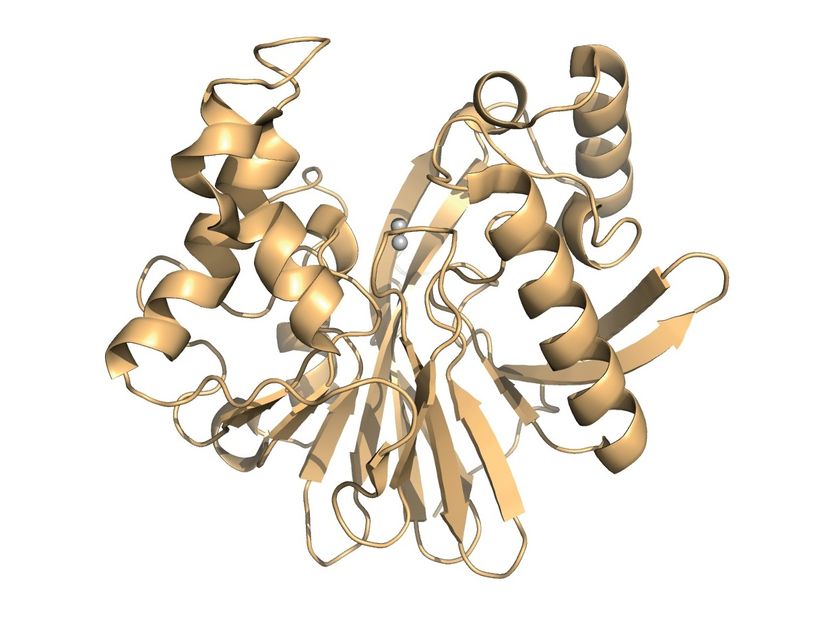

New insights into the evolution of proteins

Glycogen_storage_disease

Spinocerebellar_ataxia_type-13