A high-yield biomass alternative to petroleum for industrial chemicals

A team of University of Massachusetts Amherst chemical engineers report in Science that they have developed a way to produce high-volume chemical feedstocks including benzene, Toluene, xylenes and olefins from pyrolytic bio-oils, the cheapest liquid fuels available today derived from biomass. The new process could reduce or eliminate industry's reliance on fossil fuels to make industrial chemicals worth an estimated $400 billion annually.

Instead of buying petroleum by the barrel, chemical manufacturers will now be able to use relatively cheaper, widely available pyrolysis oils made from waste wood, agricultural waste and non-food energy crops to produce the same high-value materials for making everything from solvents and detergents to plastics and fibers.

As principal investigator George Huber, associate professor of chemical engineering at UMass Amherst, explains, "Thanks to this breakthrough, we can meet the need to make commodity chemical feedstocks entirely through processing pyrolysis oils. We are making the same molecules from biomass that are currently being produced from petroleum, with no infrastructure changes required."

He adds, "We think this technology will provide a big boost to the economy because pyrolysis oils are commercially available now. The major difference between our approach and the current method is the feedstock; our process uses a renewable feedstock, that is, plant biomass. Rather than purchasing petroleum to make these chemicals, we use pyrolysis oils made from non-food agricultural crops and woody biomass grown domestically. This will also provide United States farmers and landowners a large additional revenue stream."

In the past, these compounds were made in a low-yield process, the chemical engineer adds. "But here we show how to achieve three times higher yields of chemicals from pyrolysis oil than ever achieved before. We've essentially provided a roadmap for converting low-value pyrolysis oils into products with a higher value than transportation fuels."

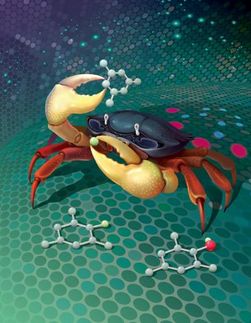

In the paper, he and doctoral students Tushar Vispute, Aimaro Sanno and Huiyan Zhang show how to make olefins such as ethylene and propylene, the building blocks of many plastics and resins, plus aromatics such as benzene, toluene and xylenes found in dyes, plastics and polyurethane, from biomass-based pyrolysis oils. They use a two-step, integrated catalytic approach starting with a "tunable," variable-reaction hydrogenation stage followed by a second, zeolite catalytic step. The zeolite catalyst has the proper pore structure and active sites to convert biomass-based molecules into aromatic hydrocarbons and olefins.

Huber, Vispute and colleagues discuss how to choose among three options including low- and high-temperature hydrogenation steps as well as the zeolite conversion for optimal results. Their findings indicate that "the olefin-to-aromatic ratio and the types of olefins and aromatics produced can be adjusted according to market demand." That is, using the new techniques, chemical producers can manage the carbon content from biomass they need, as well as hydrogen amounts. Huber and colleagues provide economic calculations for determining the optimal mix of hydrogen and pyrolytic oils, depending on market prices, to yield the highest-grade product at the lowest cost.

A pilot plant on the UMass Amherst campus is now producing these chemicals on a liter-quantity scale using this new method. The technology has been licensed to Anellotech Corp., co-founded by Huber and David Sudolsky of New York City. Anellotech is also developing UMass Amherst technology invented by the Huber research team to convert solid biomass directly into chemicals. Thus, pyrolysis oil represents a second renewable feedstock for Anellotech.

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.