Open Source Innovation Is Increasingly Being Used to Promote Innovation in the Drug Discovery Process and Boost Bottom Lines

The completion of the human genome project generated a plethora of complex information that launched the medical community into the next era of therapeutic intervention. New discoveries have led to the need for new ways to tap the vast amounts of information, so as to optimise its potential use. Coupled with this, the challenges faced by the pharmaceutical industry of coping with rising drug development costs and higher late-stage failure rates of drugs, have given rise to an urgent need for cheaper methods to improve drug pipeline productivity.

In this context, open source innovation, a concept that has been used in the information technology space for over three decades, is now successfully being applied in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries to promote innovation in the drug discovery process and boost bottom lines.

New analysis from Frost & Sullivan, Open Source Innovation in the Context of Pharma and Biotech, finds that while pharmaceutical companies have started to recognise the power of open source innovation, the industry has to push harder in order for this concept to be optimally leveraged.

The IT field has led the way in open source innovation and revealed its power to other industries. Open source innovation is a way of collaborating in the R&D of an end product, most famously software, such as Linux. Open source innovation enables information sharing across companies, institutions, areas of expertise and platforms of research.

“The key benefits of open source innovation in pharma include creativity arising from bringing together the best minds to solve a problem, and speed due to a simpler project management framework compared to internal pharma projects,” notes Frost & Sullivan Senior Research Analyst Rasika Ramachandran. “Risk sharing, greater impact due to pre-competitive nature of these projects, flexibility to discontinue non-profitable projects and finally, affordability are among its other advantages.”

These benefits are in line with the current needs of the pharmaceutical and biotechnology communities. Therefore, open source innovation is set to experience wider application in the future.

Some of the main challenges of open source innovation include economic issues such as funding as well as coordination and leadership challenges. Regulatory issues, providing incentives and availability of talent are other areas of concern.

Theoretically, open source committees can apply to the government for some part of the funding. However, if a country is staking a large per cent of its GDP on funding open source, there will need to be a more inclusive, reliable decision process. Currently, the capital markets decide which companies are funded; thus, depending on the government to regulate the industry will be a big risk.

“The most critical challenge is the funding of open source innovation projects, since, at present, government agencies are the key source of funding,” remarks Ramachandran. “However, if a larger sum of money needs to be allocated for these kinds of projects, the need for a broader and more reliable decision process rises which currently is not available.”

Governments could possibly fund open source projects through universities. The education institution could function as the coordinating arm.

The data that is gathered through this project could be stored in a repository. The information could then be accessed by all through a membership fee, a pay-per-use or pay-per-type of use mechanism.

“The outcomes of the data use should be properly attributed,” concludes Ramachandran. “Profit-sharing mechanisms should be established for innovations that are commercialised.”

Most read news

Organizations

Other news from the department business & finance

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Metabolism

Long-term_complications_of_standing

Feline_viral_rhinotracheitis

Tic

Osazone

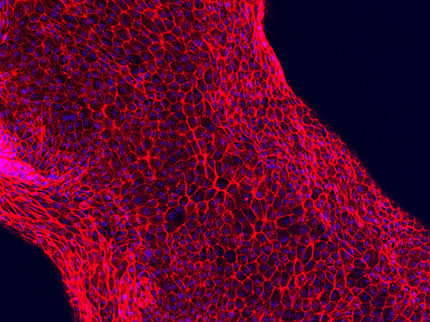

A key to metastasis - Invasive lung cancer cells display symbiosis

Western_equine_encephalitis_virus

Disease-modifying_antirheumatic_drug

Ovarian_reserve

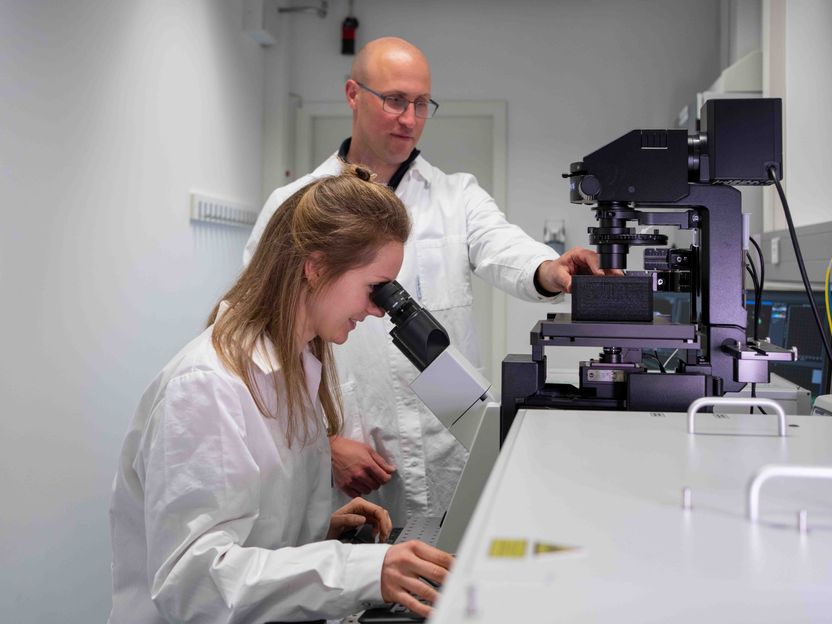

Nanotubes as optical stopwatch for the detection of neurotransmitters - New way to detect the important neurotransmitter dopamine in the brain