Glass biochips for medical engineering

Advertisement

The Fraunhofer Institute for Laser Technology ILT will be showcasing an innovative In-volume Selective Laser Etching (ISLE) process for glass on glasstec, which takes place in Düsseldorf from September 28 to October 1, 2010. This process enables micrometer-fine structures to be created in transparent material like silica glass, borosilicate glass, sapphire and ruby.

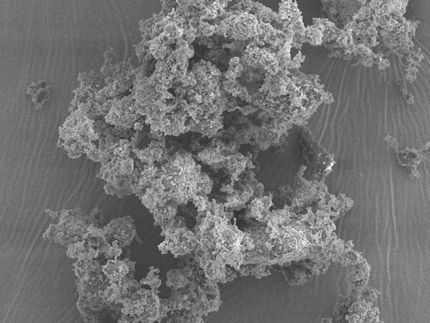

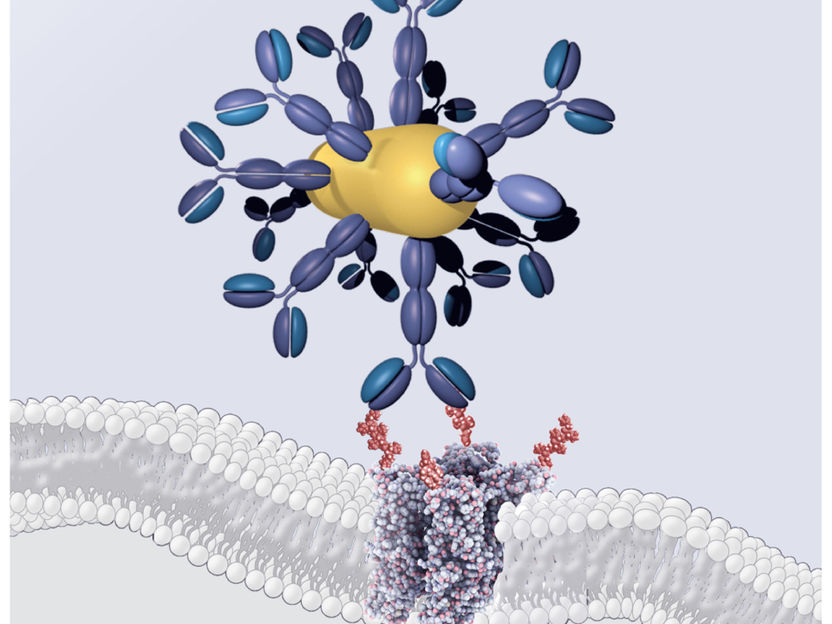

Biochips with microchannels measuring 100 micrometers in diameter, the same thickness as a strand of human hair, are used for quick tests in medical research. The channels in the small thin plates hold around a drop of fluid – blood in most cases – which is analyzed with the aid of specialized medical equipment. At present, biochips made out of plastic are used for this kind of application. However, substances from the plastic can diffuse into the test fluid and distort test results. Partners from the field of medical engineering are therefore increasingly asking for biochips made out of glass. These glass biochips are chemically neutral and essentially better suited for medical analysis applications than their plastic counterparts. The only problem so far, however, has been the lack of a suitable process for manufacturing microchannels in glass components.

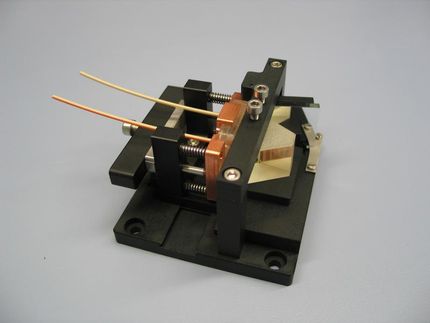

The ISLE process from Fraunhofer ILT now for the first time provides a manufacturing process for microchannels, shaped holes and cuts in transparent glass material. Selective laser-induced etching first involves irradiating the transparent component internally with a laser at the point where a structure, a channel for instance, will subsequently be created. It is important that the component is also processed right up to the edge to ensure the channel has an entry and exit. At the irradiated points, the material now has a different structure than at the untreated points. It exhibits 300-times higher etchability than the unexposed material. The component is then immersed in a bath containing special, environmentally friendly etching fluid, enabling the exposed material to be etched away. Next, the component is cleaned, leaving behind the required geometry, in this case a fine system of channels. But this process can also be used to drill holes, to manufacture tiny pipes with a wall thickness of eight 8 micrometers and measuring one millimeter in both diameter and length, or to produce miniature gears for the watchmaking industry. "The greatest challenge is to avoid damaging the glass", says Dr. Jens Gottmann, project manager at the Fraunhofer ILT. "The remelting in the glass produces stresses that cause the material to crack and make the component unusable. It's all about finding the optimum irradiation parameters, something we are constantly working on." Gottmann and his team are qualifying the process for customized applications and offer their customers a microscanner with a suitable laser to produce the tailor-made geometry.

Variation of complex geometries for prototypes

The Jülich research center is delighted with the ISLE process, particularly for producing prototypes and short-run manufacturing: The researchers there often need just a single component sample to determine the best channel design within a biochip for medical purposes. In the past, a mask had to be produced specifically to manufacture these prototypes – time-consuming, costly preparatory work. The ISLE process supports the production of complex geometries even without a mask, making it easier to vary the geometry for fine-tuning.

Potential for high-volume production

The ISLE process could also be used in future for high-volume production. Glass components have already been irradiated in the laboratory within a few seconds using a new high-power femtosecond laser. Researchers from the Fraunhofer ILT are currently developing suitable machine tools for high-volume production. Initial results show that the production of glass components is possible at costs similar to those for plastic components.

The use of float glass instead of slightly less expensive plastic pays off over the long term: The glass components boast higher quality and can be kept for longer than their plastic counterparts. Glass biochips, for instance, can be cleaned far more effectively than plastic biochips, and can even be sterilized in an oven. They can therefore be used several times, making them extremely resource- and environmentally friendly.

Apart from medical engineering, applications for the process also include precision mechanics, especially watchmaking. In future it should be possible to produce microstructured 3-D components, gears and even preassembled drives for instance, in glass. This application still requires further research, but at the same time has the potential to generate substantial financial returns.