Unlocking the secrets of cellular energy holds promise for obesity, diabetes and cancer

Researchers discover role for epigenetics in cellular energy regulation

A breakthrough on how cells regulate their energy is promising for clinical gains into diseases such as obesity, diabetes and cancer. Researchers at McGill University and University of Pennsylvania have uncovered new insights into how a protein known as the AMP-activated protein kinase, or AMPK, a master regulator of metabolism, controls how our cells generate energy. AMPK has previously been linked to a number of biological functions including cancer, diabetes, and proper immune function.

In discovering these new functions of AMPK, researchers are one step closer to understanding how cells in the body manage their energy resources. The team discovered that AMPK plays a role in this process in part by directly modifying gene expression, acting as a type of cell energy “rheostat.” Their findings are published in the journal Science.

McGill Professor Russell Jones, of the Rosalind and Morris Goodman Centre in the Department of Physiology in the Faculty of Medicine; Shelley Berger, PhD, Prof. Daniel S. Och, and David Bungard, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Berger lab, in collaboration with Dr. Craig Thompson, MD, director of the Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania, found that AMPK mediates "epigenetic regulation" of gene expression by binding directly to sites on chromosomes.

“What we have discovered is a paradigm shift concerning the role of AMPK,” Jones explained. “It has long been known that AMPK can affect how genes are turned on and off, but we have been in the dark as to how this actually works. We found that when cells are subjected to an energy crisis, AMPK goes directly to specific genes and turns them on. This allows cells to adapt to the environmental stress and lets them survive."

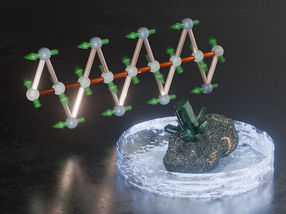

Unlike genetic changes, which involve a change or mutation in DNA sequence, epigenetic changes in the nucleus leave the DNA sequence unaltered but modify the histone proteins, which comprise the backbone of the chromosome. Histones are proteins found in the nucleus that package and order DNA into structural units. Epigentic changes alter how DNA folds in chromosomes, changing how accessible genes are to regulatory proteins and enzymes that copy genes into RNA messages.

"The discovery that AMPK goes directly to the DNA to affect gene transcription is a breakthrough in our understanding how signals from outside the cell are transmitted to change gene expression,” said Jones. "It is like an electrical circuit. We have figured out how AMPK mediates the connection."

Thus far, the investigators have identified two genes that are regulated by AMPK at the histone level in the nucleus. These initial observations were made in tissue-culture cells and the team is now working to confirm them in animal models.

AMPK’s main role is to sense cell stress. In this study, cells were stressed with ultraviolet radiation and low levels of glucose, a common source of cell energy. In the sequence of events after stress, AMPK picks up the cell-stress signal and travels to the nucleus to bind to the tumor suppressor gene p53. This in turn, causes a phosphate to be added to a histone near the p21 gene, which activates transcription. The function of the p21 protein is to stop or slow down the cell cycle.

The researchers were surprised by this finding on many fronts: This is the first time that investigators have shown that AMPK is present on chromatin, that it targets histones, and that p53 is involved in sensing stress via AMPK.

The work conducted by the researchers holds promise for new therapies for a number of diseases including diabetes and cancer. For example, AMPK is a target of metformin, the most commonly prescribed drug for the treatment of Type II diabetes. By understanding how AMPK can directly change gene expression, this may lead to the identification of new disease-associated targets and potential therapies.