'Mahjong' gene is key player when cancer, normal cells compete

A landmark study by Florida State University biologists, in collaboration with scientists in Britain, is the first to identify a life-or-death "cell competition" process in mammalian tissue that suppresses cancer by causing cancerous cells to kill themselves.

Central to their discovery was the researchers' identification of "Mahjong" –– a gene that can determine the winners of the competition through its close relationship with another powerful protein player. Lead author Yoichiro Tamori and Associate Professor Wu-Min Deng of Florida State and Yasuyuki Fujita of University College London named the newfound gene after the Chinese game of skill and luck. The findings shed light on the critical interactions between cancerous cells and surrounding tissue, and confirm that those interactions occur not only in fruit fly models but also in mammalian cell cultures.

Tamori and team found that Mahjong binds to and interacts with the tumor suppressor gene "Lethal giant larvae" (Lgl). That bond allows Mahjong to influence the outcome of cell competition, because it is mutations in Lgl –– or in genes interacting with it –– that transform a normal cell into a malignant one, triggering the lethal showdown between neighboring healthy cells and cancerous ones.

"A better understanding of the ways that inherited or acquired mutations in key proteins lead to cell competition should help foster new therapies that increase the odds of victory for normal cells," said Tamori, a postdoctoral fellow in Florida State's Department of Biological Science.

The study began with a focus on Lgl, a gene that normally prevents the development of tumors by tightly controlling cell asymmetry and proliferation. To more fully understand its role in cell competition, the Florida State and University College London biologists looked at Lgl in both fruit flies and mammals. They knew that earlier studies of Lgl's structural qualities had concluded that it worked in tandem with other proteins. To try to identify its possible partners, the researchers used a technique that worked to trap both Lgl and any proteins bound to it. They learned that Lgl had just one binding partner –– soon to be known as Mahjong.

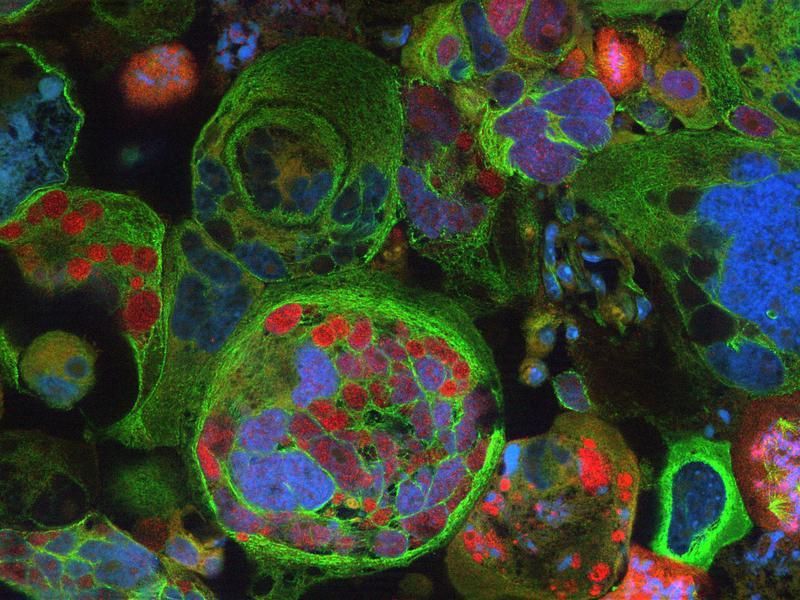

To determine if a mutation would induce cell competition in fruit flies, the Florida State biologists modified fly larvae by deleting the Mahjong gene from subsets of the wing-tissue cells. Then, using a fluorescent probe that can identify cells undergoing apoptosis (a form of programmed suicide), they saw that cell death was occurring in the Mahjong mutant cells that were adjacent to normal cells, but not in those surrounded by fellow Mahjong mutants.

"In competition with their normal neighbors," said Tamori, "cells without Mahjong were the losers."

After Tamori and Deng confirmed the role of Mahjong in fruit fly cell competition, their collaborators at University College London sought to induce competition in mammalian cells.

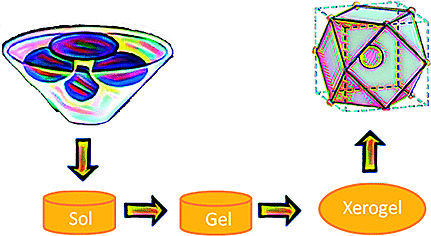

To replicate as closely as possible the occurrence of mutations caused by environmental factors, Fujita and his team engineered kidney cells whose copies of the Mahjong gene could be shut down by the antibiotic tetracycline. Before adding tetracycline, they mixed the engineered cells with normal ones and allowed them to grow and form tissue.

"When tetracycline was added to the tissue, the cells in which Mahjong had been shut down began to die, just as they had in the fruit fly," Tamori said.

"In the kidney cells, as in flies," he said, "apoptosis was only observed in Mahjong mutants when they were surrounded by normal cells. We now had a clear demonstration of cell competition in mammalian tissue, triggered by mutations in a key protein."

Next, the team sought to prevent apoptosis in cells that lacked Lgl or Mahjong by copying the remaining protein partner in larger-than-normal numbers.

"We learned that overexpressing Mahjong in Lgl-deficient cells, which typically self destruct, did in fact prevent apoptosis," Deng said. "But, in contrast, we found that overexpressing Lgl in Mahjong-deficient cells did not prevent cell suicide."

Original publication: "Involvement of Lgl and Mahjong/VprBP in Cell Competition."; PLoS Biology 2010.