Pocket-sized breath test for stomach bacteria

Mini sensor analyses breath for infection with Helicobacter pylori

Stomach ulcers, gastritis and even stomach cancer are often the result of an infection with Helicobacter pylori. If the bacterium remains unrecognised for a long time, this can have serious consequences. Until now, however, diagnostic detection has been time-consuming and expensive. Researchers at Ulm University have now developed a miniaturisable sensor system for the mobile analysis of breath that is effective, fast and inexpensive. The research team uses a biological survival trick of the stomach germ to detect the bacterium. The research team demonstrates how the technology works in the journal ACS sensors.

"We have developed an infrared-based sensor system that can detect Helicobacter pylori using a mobile breath test. The technology has great potential for miniaturisation and is cost-effective," says Professor Boris Mizaikoff. The head of the Institute of Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry at Ulm University and the Hahn-Schickard site in Ulm developed the mini-sensor together with researchers from his institute. The team is now working on a smartphone-compatible technical solution for individualised and mobile use.

The scientists in Ulm are using a spectroscopic method from the mid-infrared range (MIR) to analyse the air we breathe. Infrared spectroscopy is cheaper than the mass spectrometry traditionally used for this purpose and can be easily miniaturised. "MIR spectroscopy is particularly suitable for the gas-phase analysis of molecules such as carbon dioxide, which absorb light particularly well in the infrared spectrum," says Dr Gabriela Flores Rangel. The chemist is a postdoctoral researcher in Mizaikoff's working group and corresponding author of the ACS Sensors study. Dr Lorena Díaz de León Martínez, also a postdoc at the Ulm Institute, was also involved in the project.

The researchers used a biological trick of the bacterium

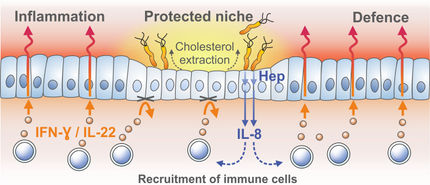

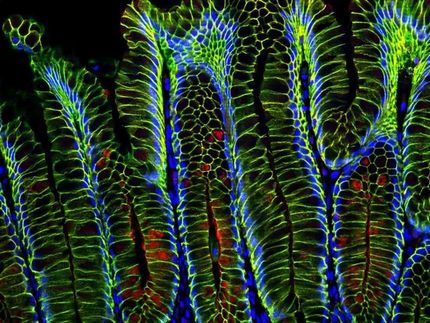

Helicobacter pylori is a survivor. The acid-resistant rod-shaped bacterium colonises the stomach, a place where countless pathogens would otherwise die. To protect itself against the aggressive stomach acid, the stomach germ erects a chemical shield. It is helped by an enzyme that Helicobacter pylori produces itself: urease. The enzyme breaks down urea into carbon dioxide and ammonia, consuming water in the process. The bacteria use the ammonia, an alkaline nitrogen compound, to chemically buffer the stomach acid. "However, we are interested in the carbon dioxide, i.e. the by-product of the bacterially stimulated hydrolytic catalysis," says Mizaikoff.

In order to distinguish this "tell-tale" carbon dioxide from the carbon dioxide that humans exhale anyway, the researchers are using a labelling method that is commonly used in chemical analysis and Medicine diagnostics. The urea administered to the test subjects for the urease test contains "labelled" carbon (13C instead of 12C). 13C is a carbon isotope that absorbs infrared light at a lower wavelength than 12C. "We can measure these differences in absorption using MIR spectroscopy. They tell us how much carbon comes from the bacterially cleaved urea and thus indicate whether an infection with Helicobacter pylori is present or not," explains Flores Rangel.

So far, tests for Helicobacter pylori can only be carried out in a clinical context. In the invasive procedures, tissue samples from gastrointestinal endoscopies are analysed bacteriologically. Non-invasive tests for analysing breath are still based on methods such as mass spectrometry, which are very complex and expensive.

The reaction space has been reduced in order to increase the light-gas interaction

Mizaikoff and his team are relying on another innovation for their infrared sensor system. In order to intensify the reaction between the sample molecules and the infrared radiation, they have reduced the size of the reaction space. A so-called substrate-integrated hollow waveguide (iHWG) is used. The reaction chamber consists of two aluminium plates that are sealed airtight with an epoxy resin compound. A channel is embedded in the base plate through which the breathing air is conducted and which also serves as a miniaturised gas cell and IR optical waveguide. On the sides, infrared light-transmitting barium fluoride windows ensure that the MIR radiation is reflected along the channel and can measure the wavelengths absorbed by the labelled and unlabelled carbon dioxide. "We have already been able to reduce the size of the gas cell from the original ten centimetres to three centimetres without losing measurement accuracy," emphasises Mizaikoff. To further exploit the miniaturisation potential of the sensor system, lasers or light-emitting diodes can also be used as a light source for IR spectroscopy.

The scientists assume that the system can be simplified and miniaturised in such a way that the cost of the smartphone-compatible mini-sensor can be reduced to around 20 euros. This is good news for all people struggling with a Helicobacter pylori infection: in future, it will be possible to detect the stomach germ quickly and easily with a mobile breath test; what a help for diagnostics and therapy!