Why liver inflammation can damage the kidneys

The hepatitis E virus actually infects the liver. However, infected liver cells secrete a viral protein that reacts with antibodies in the blood - and as a complex can damage the filtering devices in the kidneys, as researchers at the University of Zurich and University Hospital Zurich have demonstrated for the first time.

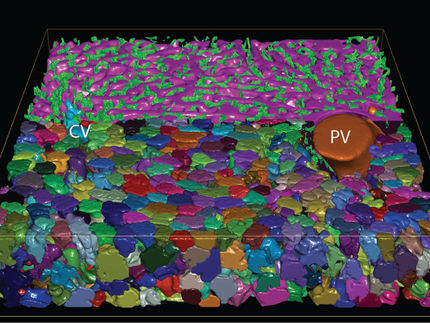

Infected liver cells secrete a viral protein that reacts with antibodies in the blood - and as a complex damages the filtering devices in the kidneys.

Achim Weber/UZH

The hepatitis E virus infects around 70 million people every year. "This infection is the most common form of viral hepatitis and a major global health problem," says Achim Weber, Professor of Pathology at the University of Zurich (UZH) and University Hospital Zurich (USZ). In most cases, the infection is asymptomatic or mild. However, sometimes it is accompanied not only by severe damage to the liver, but also by kidney damage.

Insight gained into the disease mechanism

"This has been known for some time, but nobody knew exactly why," says Weber. Now the two nephropathologists Birgit Helmchen and Ariana Gaspert and the molecular biologist Anne-Laure Leblond in his team - in collaboration with researchers from France and colleagues at various hospitals in Switzerland - have clarified the disease mechanism by examining tissue samples from sick people.

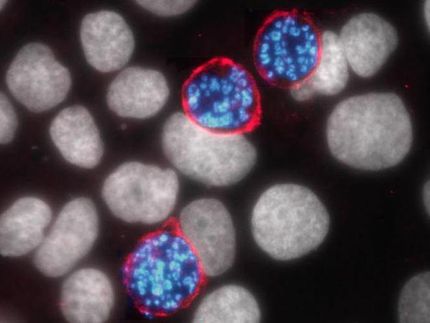

The infected liver cells produce a large excess of a viral protein that can form a viral envelope with its own kind. Because the genetic material of the virus is replicated to a much lesser extent, the vast majority of envelopes remain empty when they are excreted from the liver cells. They then enter the bloodstream, where they are recognized by the immune system. The immune system forms antibodies that attach themselves to the viral proteins.

These viral envelope-antibody complexes are then deposited in the blood filtering devices of the kidneys, the so-called glomerula. If the complexes accumulate faster than they are broken down, they can damage the glomerula - and trigger so-called glomerulonephritis: a pattern of damage that, in the worst case, leads to kidney failure.

Hepatitis E often remains undetected

Weber and his team of researchers came across this mechanism when they were investigating the cause of death of a patient who had received a new kidney years ago. "It was clear from his medical records that his chronic hepatitis E was not immediately recognized," says Weber. This is not atypical, as the disease still receives too little attention in Europe.

"During my studies, I learned that hepatitis E only affects people in Asia, Africa and Central America," says Weber. It is only gradually being recognized that people in Europe can also become infected with the hepatitis E virus, especially if their immune system is weakened - and the infection can therefore become established or chronic.

Useful detection methods

"We hope that our discovery will help to raise awareness of hepatitis E in this country too," says Weber. The findings that have just been published are also important for everyday diagnostics: the detection methods for the proteins of the hepatitis E virus developed by Weber's team will now enable pathologists to determine whether the pathogen is involved in glomerulonephritis.

"This benefits those affected," says Weber. This is because if the hepatitis E virus determines the course of the disease, the treating physicians can take timely countermeasures, for example by administering substances that inhibit the replication of the virus - and thus prevent an impending collapse of the kidney.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.

Original publication

Anne-Laure Leblond, Birgit Helmchen, Maliki Ankavay, Daniela Lenggenhager, Jasna Jetzer, Fritjof Helmchen, Hueseyin Yurtsever, Rossella Parrotta, et al.; "HEV ORF2 protein-antibody complex deposits are associated with glomerulonephritis in hepatitis E with reduced immune status"; Nature Communications, Volume 15, 2024-10-14