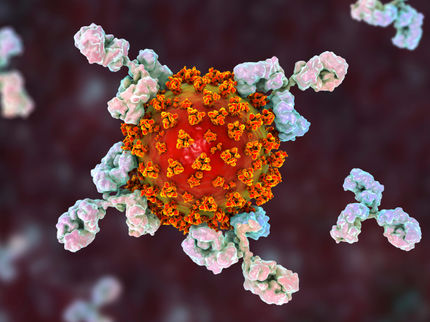

New vector vaccine against COVID-19 provides long-term protection

Advertisement

Established vaccines against Covid-19 are known to have the disadvantage that the initially good protective effect wears off relatively quickly. This makes repeated booster vaccinations necessary. Against this background, a novel vector vaccine developed at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) is interesting because it shows a sustained immune response over significantly longer periods of time in animal models. Another plus: the vehicle - the vector - used to transport the information for the coronavirus spike protein in the vaccine is an animal cytomegalovirus (MCMV) that cannot pose a threat to humans.

In 2022, researchers from the "Viral Immunology" department headed by Prof. Luka Cicin-Sain at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research reported on the novel vector vaccine for the first time. The promising profile of the MCMV-based vaccine, which was already apparent at the time, has since been confirmed. A recent publication, in which other national and international research institutions such as the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), the Max Delbrück Center in Berlin and the University of Rijeka in Croatia were involved, underpins the long-lasting and broad immune response in the mouse model.

The use of an animal cytomegalovirus as a vector is a clever move. In vector vaccines, viruses are used as vehicles to introduce components of the pathogen against which the vaccine is directed into the human body. In vaccines against COVID-19, the gene for the blueprint of the spike protein that anchors the coronavirus to the host cells is integrated into the vector viruses.

Mouse CMV is considered safe for humans

Many people are worried that vector viruses in vaccines could be dangerous to them. Human viruses that are used as vectors actually have to be deactivated first. MCMV, however, can be used as it is. Cytomegaloviruses are highly host-selective. This means that the MCMV infects the mouse, but cannot multiply in humans, as two of the first authors, Dr. Kristin Metzdorf and Dr. Henning Jacobsen, explain. This is one of the reasons why MCMV is ideal as a vector for vaccines.

The researchers see the big advantage in the long-lasting vaccination response that can be achieved with the MCMV vaccine after just one dose. Using an animal model, it was shown that the concentration of antibodies available for defense against the pathogen in the event of a subsequent infection with the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus remains stable over a period of six months after vaccination. Results from research colleagues at the University of Rijeka in Croatia suggest that the protective effect lasts even longer.

The immune system takes a two-pronged approach to fighting pathogens: firstly, highly specific antibodies are formed that are directed against certain structures of the attacker and render it harmless. The second track consists of the mobilization of specific immune cells that recognize the pathogen in infected cells and actively fight it. So-called CD8+ T cells play the central role here. After vaccination with the new vaccine against COVID-19, the freely circulating antibodies in the blood are permanently increased and CD8+ T cells directed against the coronavirus are also permanently ready for action.

Switching between resting and active mode

Research is now being conducted into why the MCMV vaccine has a comparatively long-lasting protective effect. One assumption already exists: cytomegaloviruses have the ability to seek out niches in their host where they can hide and remain inactive in resting mode for a long time. Only when the host organism's immune defenses weaken do they switch to active mode and can then cause signs of illness. The MCMV vector viruses presumably also try to settle in the human organism, but because humans are not the right host for them, reactivation does not work. The human immune system does not allow mouse viruses to reappear in the blood and takes action against them as soon as they produce proteins and before infectious particles are formed. In this way, so the theory goes, the immune defense is repeatedly stimulated and the vaccination effect is maintained.

And there is another interesting phenomenon with regard to the mutability of the coronavirus: the researchers used the spike gene of the very first SARS-CoV-2 variant for the new vaccine. As expected, specific antibodies are initially formed against this original spike protein after administration of the MCMV vaccine. Interestingly, however, some time after vaccination, not only antibodies against the original are found, but also antibodies against protein variants such as the Omikron variant. This is probably due to a mechanism of the immune system that serves to increase resistance to attackers through mutations (genetic changes) in the relevant immune cells. According to the researchers, the fact that this mechanism is particularly well supported by the MCMV vaccine is a further advantage of this technology.

Two at one stroke

The favorable all-round profile of the MCMV vector is completed by its high capacity to take up foreign genes. These are exchanged for viral genes that are not essential for the integrity of the virus. Theoretically, it is possible to introduce several different genes of a pathogen into the MCMV at the same time and thus increase the vaccination effect or the spectrum of efficacy against variants. It is also conceivable to use this vector to produce combination vaccines that provide immunity to various diseases in one go. The combined vaccination against COVID-19 and influenza would be a useful example.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.