Reckoned without one's host: Transmission of tuberculosis does not only depend on the pathogen

Geographical overlap between pathogen and host has a measurable influence on the transmissibility of the tuberculosis pathogen

Advertisement

Different groups of TB bacteria exist worldwide with different regional distribution: some are generalists and can be found on many continents, others are very limited in their spread. An international team of researchers has now been able to show for the first time that the specialist strains spread more effectively among suitable hosts from the same geographical area, whereas generalist strains can spread in different host populations from a variety of geographical settings. The transmissibility of tuberculosis therefore depends not only on the pathogen or the host but also on their combination.

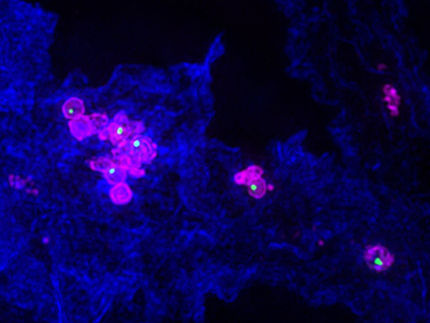

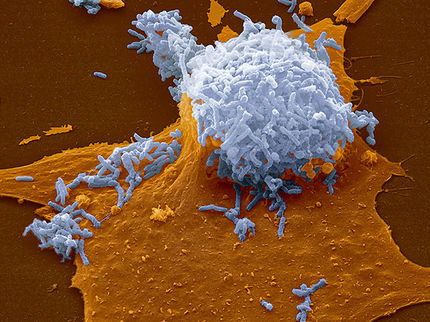

Scanning electron micrograph of a human macrophage at 15000x magnification after phagocytosis of Y-irradiated, inactivated M. africanum.

Susanne Homolka/FZB

With over 1.4 million deaths per year, tuberculosis is still one of the most dangerous infectious diseases worldwide. A total of ten different genetic lines of the pathogen, pathogens of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (Mtbc) , are found in the world: Strains of the L4 lineage are most common in Europe and North America, while strains of the L2 lineage are predominant in Asia. Africa is the only place where strains of lineages 5 and 6 are regularly found. While strains of lineages L2 and L4 are widespread and common, strains of some lineages of the African region have rarely been isolated outside the continent and have a limited geographical distribution.

It is therefore assumed that geographically restricted lineages of the Mtbc spread more effectively among sympatric hosts (“fitting”), i.e. those from the same geographical area, and show lower transmissibility among allopatric (“non fitting”) hosts, i.e. people from different geographical regions. Until now, however, this assumption could not be proven as there were no large data sets with clinical tuberculosis data and high-resolution pathogen sequences.

Now, an international team of scientists from the Research Center Borstel, Leibniz Lung Center, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and Harvard Medical School in Boston has succeeded in proving this hypothesis for the first time: Using pathogen genome and contact tracing data from 2,279 tuberculosis cases linked to 12,749 social contacts from three low-incidence cities, the researchers were able to show that strains of geographically restricted Mtbc lineages are less transmissible than strains of lineages that have a wide global distribution. The data comes from Hamburg, New York and Amsterdam and was compiled in cooperation with the respective health authorities. The team was able to show that allopatric pathogen-host exposure, where the pathogen and host originate from non-overlapping areas, was 38% less likely to infect contact persons than sympatric exposure.

These epidemiological observations were then supported by laboratory experiments. Using a macrophage infection model, it was shown that a lower uptake and growth of cells of Mtbc strains in allopatric macrophages was observed after the first exposure. These studies support the results of the epidemiological analysis and will be extended to further host-strain combinations in future projects.

The researchers conclude that the long-term coexistence of Mtbc strains and humans has led to different transmissibility of Mtbc strains and that this differs depending on the human population. “These differences in transmissibility mean that strains of geographically restricted Mtbc lineages have a barrier to their ability to spread to other geographic regions,” says Dr. Dr. Matthias Gröschel, first author of the study and physician at Charité’s Speciality Network Infectious Diseases and Respiratory Medicine. “In subsequent work, we now want to aim to understand the molecular basis of allopatric and sympatric infections.”

This information may be helpful in the future to personalize environmental investigations and, for example, to track high-risk contacts such as sympatric host-pathogen contacts with higher priority. These specific virulence mechanisms could also be important in the development of drugs.

“For the first time, the work allows a more precise understanding of the host-pathogen interaction in tuberculosis on a global level,” says Prof. Stefan Niemann, head of the study at the Research Center Borstel, Leibniz Lung Center. “We are working hard to elucidate the pathobiological mechanisms”.

Original publication

Matthias I. Gröschel, Francy J. Pérez-Llanos, Roland Diel, Roger Vargas, Vincent Escuyer, Kimberlee Musser, Lisa Trieu, Jeanne Sullivan Meissner, Jillian Knorr, Don Klinkenberg, Peter Kouw, Susanne Homolka, Wojciech Samek, Barun Mathema, Dick van Soolingen, Stefan Niemann, Shama Desai Ahuja, Maha R. Farhat; "Differential rates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission associate with host–pathogen sympatry"; Nature Microbiology, 2024-8-1