Reprogrammed fat cells support tumor growth

mutations of the tumor suppressor p53 not only have a growth-promoting effect on the cancer cells themselves, but also influence the cells in the tumor's microenvironment. Scientists at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the Weizmann Institute in Israel have now shown that p53-mutated mouse breast cancer cells reprogram fat cells. The manipulated fat cells create an inflammatory microenvironment, impairing the immune response against the tumor and thus promoting cancer growth.

No other gene is mutated as frequently in human tumors as the gene for the tumor suppressor p53. In around 30 percent of all cases of breast cancer, the cancer cells show mutations or losses in the p53 gene. These mutations restrict the ability of p53 to acta as a "cancer brake" p53 and to prevent the development and progression of cancer.

The effects of p53 mutations in the cancer cells themselves have already been intensively researched. However, the understanding that p53 mutations in cancer cells can also affect cells in the tumor's microenvironment - and thus additionally drive cancer growth - is only slowly growing.

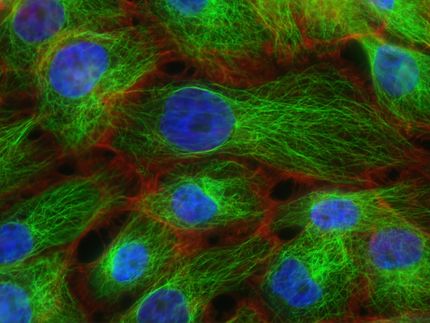

A team of researchers led by Almut Schulze from the DKZF and Moshe Oren from the Weizmann Institute in Israel investigated the effects of p53 mutations in breast cancer cells on fat cells, known as adipocytes. During the progression of breast cancer, adipocytes, one of the main cell types in breast tissue, undergo a transformation. Research results indicate that this increases the aggressiveness and resistance to therapy of the surrounding breast cancer cells.

Schulze and Oren's team have now demonstrated this in adipocytes from mouse breast tissue: The cancer-promoting properties of adipocytes are potentiated when the breast cancer cells carry p53 mutations.

The researchers treated immature adipocytes with culture medium in which breast cancer cells with or without p53 mutations had previously grown. This treatment triggered profound changes in metabolism and gene activity in the adipocytes and increased the production of pro-inflammatory messengers. The maturation of the adipocytes was prevented, while mature fat cells were returned to an immature stage. These effects were only mild after treatment with cell culture media from breast cancer cells with functioning p53, but were very clear in the case of medium from cancer cells with mutated p53.

The researchers then transferred breast cancer cells with mutated or functional p53 together with pre-treated fat cells to mice and compared the resulting tumors. If p53 was mutated in the cancer cells, the number of immunosuppressive myeloid cells in the tumor increased. The migrated immune cells carried more PD-L1 on their surface, which acts as a potent brake on the immune defense of tumors.

A particularly surprising result was that breast cancer cells with certain p53 mutations were able to reprogram neighboring precursor fat cells - directly or indirectly - to be even more pro-inflammatory than breast cancer cells that had completely lost the tumor suppressor p53.

"p53 defects in breast cancer cells appear to be the central driver of tumor-promoting reprogramming of fat cells," summarizes Almut Schulze, who led the study together with Moshe Oren. "Fat cells are an essential component of breast tissue and can therefore have a massive influence on tumor progression. A detailed understanding of the interaction between p53-mutated cancer cells and adipocytes could therefore provide new clues as to how the progression of breast cancer can be halted."