Bacteria contribute to the modulation of animal behaviour

Research team uses the example of the freshwater polyp Hydra to show how nerve cells and microorganisms cooperate to control the animals' feeding behaviour

Advertisement

An increasingly important field of work in modern life sciences is the study of the symbiotic coexistence of animals, plants and humans with their specific microbial populations. In recent years, researchers have gathered growing evidence that the composition and balance of the microbiome plays a decisive role in the function and health of the organism as a whole. They have identified a fundamentally important aspect in these functional relationships in the communication between nerve cells of the host and its microbiome, which was first established very early in evolution. The significance of this cooperation and how these interactions affect behaviour is still largely unknown. In a recent study, a research team from the Collaborative Research Center (CRC) 1182 "Origin and Function of Metaorganisms" at Kiel University has gained new insights into the cooperation between the nervous system and the microbiome. Using the freshwater polyp Hydra as an example, the Kiel researchers investigated the neuronal basis of their feeding behaviour and whether and in what way the microbiome intervenes in this behaviour. In doing so, they were able to prove mechanistically for the first time that a microbiome with reduced diversity affects the function of certain nerve cells and thus alters the feeding behaviour.

Complex cooperation of nerve cells controls the feeding behaviour of Hydra

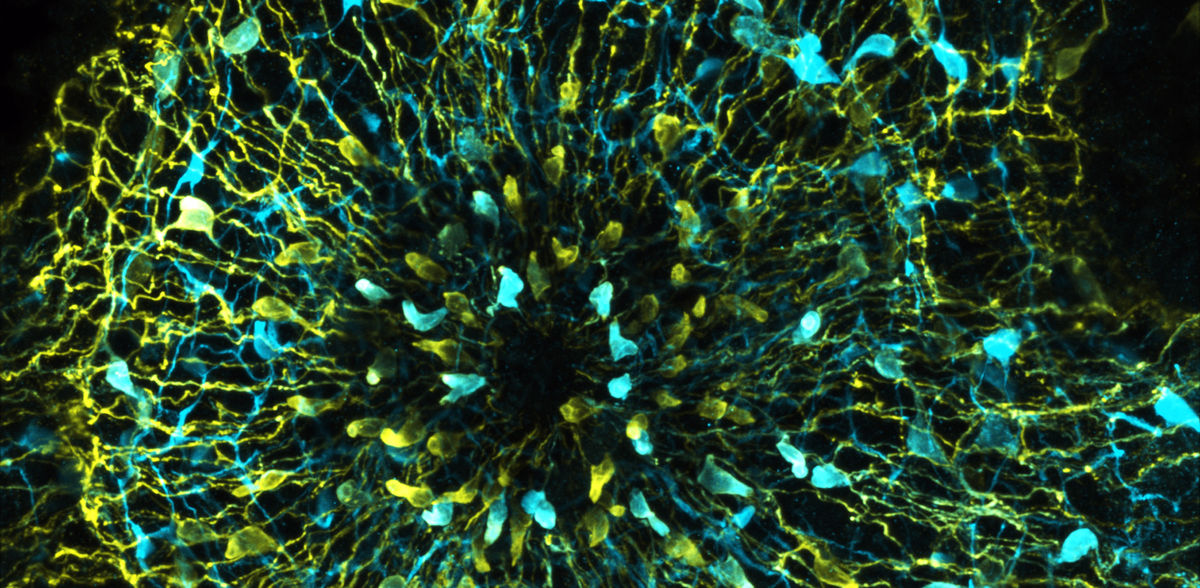

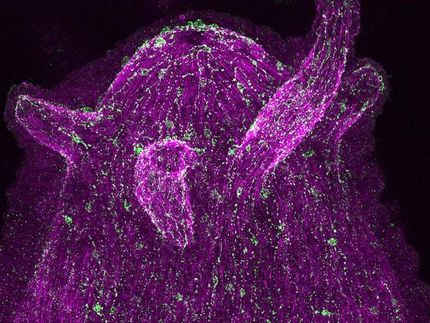

The freshwater polyp Hydra is a cnidarian about one centimetre in size that lives in the shallow waters of lakes attached to aquatic plants and feeds on microscopic crustaceans, among other things. To catch its prey, Hydra executes a coordinated and relatively fast behavioural programme. "This behaviour can be well studied experimentally, as it can be triggered not only by the living prey, but also by the peptide glutathione, which can be fed to the animals in the culture dishes," explains Christoph Giez, CRC 1182 member and PhD student in the Cell and Developmental Biology group at the Zoological Institute. "Underlying the feeding behaviour is a neuronal control that is significantly more complex than was previously assumed from the simple nerve network of Hydra," Giez continues. Using a calcium-based visualisation method, the research team was able to observe the nerve populations involved in feeding behaviour in real time in the living animal and thus identify the neuronal circuit involved.

Composition of the microbiome influences natural feeding behaviour

In order to test a connection between the microbiome and feeding behaviour, the scientists first examined artificially germ-free animals: Hydras without a microbiome showed a clearly altered behavioural pattern, which was mainly expressed in a shorter duration of mouth opening. "By adding the microbiome again, the normal feeding behaviour was restored in these animals. This allowed us to prove the direct influence of the microbiome," Giez emphasises.

In order to find out which bacteria have a particularly significant influence, the Kiel researchers first colonised germ-free animals with one defined bacterial species each in the next step. "A particularly interesting effect was seen when colonising with the bacterium Curvibacter. The feeding behaviour of animals colonised only with Curvibacter is very strongly impaired: These animals can only open their mouths to a very limited extent," Giez continues.

In further studies, Curvibacter was found to produce the amino acid glutamate, which also plays an important role in human metabolism. When the microbiome is greatly reduced in composition and only Curvibacter is present, glutamate accumulates, binds to neurons and leads to a blockage of the mouth opening. The inhibitory effect of the Curvibacter bacteria is reversed as soon as the remaining members of the microbiome are also reintroduced to the tissue.

"Overall, we were able to prove that even in phylogenetically ancient animals, a diverse microbiome is necessary for normal feeding behaviour. If the composition of this microbiome is severely disturbed, significant changes in behaviour occur," summarises Professor Thomas Bosch, head of the Cell and Developmental Biology group. The researchers have gathered evidence that this is due to interactions between the different members of the microbiome. If there is a species-rich, "normal" microbiome, the glutamate produced is taken up and utilised by other bacterial species and the neuronal circuit responsible for feeding behaviour is not disturbed.

Hydra opens up spectrum of novel research perspectives

With their mechanistic evidence of the collaboration between the microbiome and the nervous system, the new research results of the CRC 1182 team provide important new approaches for in-depth research. "Our study opens the door for further research into the effects of the interplay between the microbiome and the nervous system on the functions of the whole organism. Among other things, we want to find out in the future whether and how microorganisms are already involved in the formation of the nervous system during embryonic development and what part the microbiome plays in the production of neurotransmitters," Bosch emphasises.

In the long term, the elucidation of these individual building blocks will result in various fascinating research perspectives that are also aimed at improving human health. "Perhaps with a better understanding of the interactions between nerve cells and bacteria in the model animal Hydra, we will also be able to look into the mechanisms that can lead to neurological and neurodegenerative diseases in humans. Although the incidence of these diseases is very high worldwide, the mechanisms of their pathogenesis are not yet understood," says Bosch, spokesperson of CRC 1182.