Scientists identify virulent new strains of Ug99 stem rust

Wheat experts report progress toward replacing 5 percent of vulnerable fields in nations at risk

Advertisement

Four new mutations of Ug99, a strain of a deadly wheat pathogen known as stem rust, have overcome existing sources of genetic resistance developed to safeguard the world's wheat crop. Leading wheat experts from Australia, Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas, who are in St. Petersburg, Russia for a global wheat event organized by the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative, said the evolving pathogen may pose an even greater threat to global wheat production than the original Ug99.

The new "races" have acquired the ability to defeat two of the most important stem rust-resistant genes, which are widely used in most of the world's wheat breeding programs.

"With the new mutations we are seeing, countries cannot afford to wait until rust 'bites' them," said Dr. Ravi Singh, distinguished senior scientist in plant genetics and pathology with the Mexico-based International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). "The variant of Ug99 identified in Kenya, for example, went from first detection in trace amounts in one year to epidemic proportions the next year."

"Already, most of the varieties planted in the wheat fields of the world are vulnerable to the original form of Ug99. We will now have to make sure that every new wheat variety we release has iron-clad resistance to both Ug99 and the new races," said Singh.

The reddish-brown, wind-borne fungus known as Ug99 has decimated up to 80 percent of Kenyan farmers' wheat during several cropping seasons, and scientists estimate that 90 percent of the wheat varieties around the world lack sufficient resistance to the original Ug99. Starting five years ago, in response to evidence of Ug99's virulence, researchers expanded breeding programs and collaborated with each other in a kind of "shuttle breeding diplomacy" to identify wheat varieties that could resist the new strain. But the new mutations — identified last year in South Africa — will make wheat crops more vulnerable as pathogens now will find new wind trajectories for migration.

First discovered in Uganda in 1999, the original Ug99 has also been found in Kenya, Ethiopia, Sudan, Yemen and Iran; a Global Cereal Rust Monitoring System, housed at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), suggests it is on the march toward South Asia and beyond. Its trajectory and evolution are of particular concern to the major wheat-growing areas of Southern and Eastern Africa, the Central Asian Republics, the Caucasus, the Indian subcontinent, South America, Australia and North America.

"We do not have as much information as we would like on the aggressiveness of the pathogen," said David Hodson, Head of the GIS Unit at FAO. "The original race, Ug99, does not seem to have increased as much as originally feared, given its highly virulent nature. But the new variants pose a grave challenge that we are addressing in collaborations around the world."

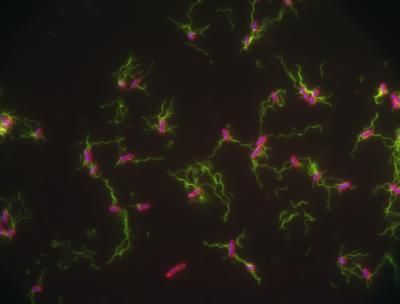

The wheat rust pathogen enters the stems of a wheat plant and destroys the vascular tissue. There are three rusts that pose threats to wheat, but stem rust, of which Ug99 is a variant, is the most feared. It causes plants to fall over and can lead to the loss of an entire harvest. The introduction of one variant in just one part of the world can cause enormous losses, according to the scientists.

Hodson noted that wheat scientists and farmers alike are now mobilizing to identify and fight the virulent new forms of Ug99. Scientists at the meeting in St. Petersburg, hosted by the N.I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry, said they are staying a few steps ahead of the rapidly evolving pathogen. They note that collaborative research and breeding programs are producing promising new lines that exhibit excellent defenses against Ug99 and its "daughter" stem rust strains.

"We are ready," said Dr. Mahmoud Solh, Director General of the Syria-based International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA). "Wheat rust researchers around the world have united in an unprecedented collaboration to monitor the spread of wheat rust, find new sources of rust resistance from wild relatives of wheat, and deploy varieties with durable resistance."

But the burning question, according to Dr. Solh and his colleagues, is whether policymakers will provide the sustained support needed to remain prepared for future challenges.

"Wheat is the primary source of calories for millions of people worldwide, and accounts for around 30 percent of global grain production and 44 percent of cereals used as food," said Dr. Solh. "Globally, wheat provides nearly 55 percent of the carbohydrates and 20 percent of the food calories we consume every day."

The last major stem rust epidemic swept across North America's wheat fields in the early 1950s, when the disease destroyed as much as 40 percent of the continent's spring wheat crop. The crisis gave birth to a new form of international cooperation among wheat scientists worldwide. Spearheaded by Nobel Laureate wheat scientist Norman Borlaug, the initiative developed wheat varieties that resisted stem rust for more than four decades.

"The problem is that once they get to an epidemic level, they are very hard to stop," Singh said. "In a raging epidemic, even chemicals are of limited use."

Ironically, the very success of their work eventually led to complacency; in the 1990s, for instance, just before the discovery of Ug99, the United States had only one scientist with expertise in stem rust. Before his death last year, Borlaug drew the world's attention to the threat the emerging pathogen poses to world food security, and warned of its newfound ability to overcome the resistance that had kept stem rust at bay for more than 40 years. And now virulent mutations of Ug99 have appeared in South Africa, according to new research presented in St. Petersburg.