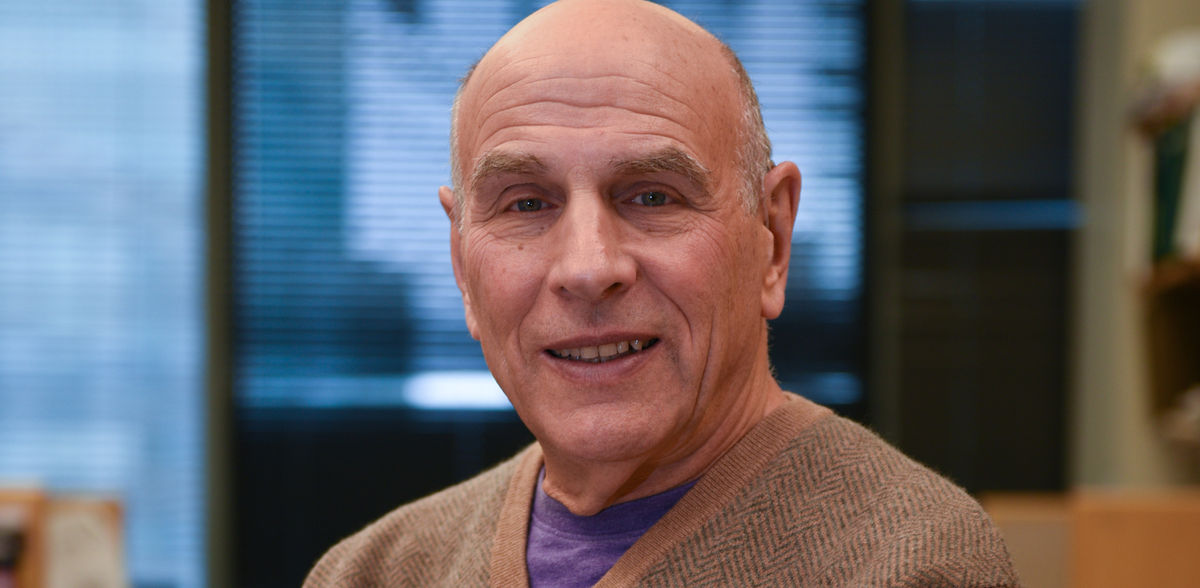

Dennis L. Kasper to be awarded the Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Prize 2024

Physician and immunologist Dennis L. Kasper (80) of Harvard Medical School will receive the 2024 Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Prize, the Scientific Council of the Paul Ehrlich Foundation announced. Kasper discovered the to date only known words of the biochemical language with which bacteria that populate our colon educate our immune system, thereby ensuring its healthy development. In so doing, the prize winner has opened up a new and dynamic field of research, in which concrete starting points for the treatment of severe autoimmune diseases are already emerging.

FRANKFURT. Around ten trillion bacteria live in the large intestine of every human being. They make up the majority of our microbiome, i.e., all the microorganisms that settle on our skin and in our body cavities. That bacteria are not only harmful but also beneficial has been gradually recognized by biomedical sciences since the analysis of antibiotic side effects in the 1960s. But how bacteria communicate useful messages to their hosts' immune systems in particular has long remained an enigma. Dennis Kasper has solved it using the bacterium Bacteroides fragilis as a model organism. He discovered two special molecules with the help of which this intestinal microbe educates the immune system of its hosts to act in moderation and not to attack its own body. “The award winner was the first to succeed in uncovering communication channels in the superorganism that humans and their microbiome form,” says Prof. Dr. Thomas Boehm, Chairman of the Scientific Council of the Paul Ehrlich Foundation. “Through him, we have learned which signals intestinal bacteria use in our immune system to ensure a healthy balance between aggressiveness and dampening of inflammation. This will have far-reaching clinical consequences.”

B. fragilis is a bacterial species that colonizes our intestines particularly early and in large numbers after birth. Dennis Kasper began to study it in the mid-1970s because it plays an often-fatal role in injury-related infections of the normally sterile abdominal cavity, due to its resistance to penicillin. Within the intestine, however, B. fragilis is not a pathogen. Some bacteria protect themselves from their environment by forming a capsule. Kasper discovered that in B. fragilis, this capsule is characterized by an extraordinary variability. While most bacteria equip their capsule with only one polysaccharide, B. fragilis can produce eight different ones and combine them into ever new patterns. In this way, it appears to its host's immune system in constantly changing garb, eluding its grasp, and is thus able to influence it in good disguise. For this purpose, B. fragilis primarily uses the most commonly expressed of these capsule sugars, which Kasper named PSA. In this very large molecule, up to 200 units of four different sugars each are linked together and attached to the membrane with a fat-like anchor. Kasper discovered that dendritic cells – which act as "sentinel cells", informing the immune system about the state of the body – take up the sugar, process it and display it on their surface, thereby stimulating the production of certain T cells.

In immunology, this so-called MHC-II pathway of antigen presentation previously was considered to be reserved for foreign proteins invading from the outside and fighting the microbe. With his fundamental discovery, Kasper broke this dogma in 2004. He showed that the bacterial sugar provides a balance between different types of T cells via the MHC-II pathway, thereby ensuring that the development of immune-relevant organs such as the spleen also proceeds in a coordinated manner. PSA can also program dendritic cells to stimulate regulatory T cells to produce interleukin-10, one of the immune system's most important anti-inflammatory messengers. The award winner has deciphered in detail the signaling pathways through which PSA exerts this effect.

While B. fragilis controls the maturation of a balanced population of regulatory T cells in its host organism throughout its life with the polysaccharide PSA, it intervenes in the immune system’s development with another molecule only for a brief time, but nevertheless effectively. As Kasper demonstrated, this molecule is the glycosphingolipid GSL-Bf717, a fat-like substance. In the weeks and months after our birth, this bacterial lipid inhibits the proliferation of natural killer T cells (NKT cells), which can trick the immune system into excessive inflammatory responses and attacks on its own body. Because it bears structural similarity to molecules that promote NKT proliferation, the bacterial lipid displaces many of these molecules from their binding sites, preventing the development of an oversized NKT pool. Adult mice who were exposed to the bacterial sphingolipid as newborns have a significantly lower risk of developing an autoimmune disease such as ulcerative colitis.

Thanks to Dennis Kasper’s decades of persistent work, connections between the gut microbiome and the immune system can for the first time be established causally and no longer merely associatively. The anti-inflammatory effect of the "B. fragilis words" he discovered is not limited locally to the gut. It also manifests systemically. GSL-Bf717 not only prevents chronic intestinal inflammation, but also allergy-related diseases such as asthma. The potential of the polysaccharide PSA, in turn, has spurred research into the signaling axis between the gut and the brain. There is convincing evidence that this bacterial sugar counteracts the breakdown of the myelin sheaths of nerve fibers in experimental multiple sclerosis (MS).

Dennis L. Kasper (laboratory homepage) has been William Ellery Channing Professor of Medicine since 1989, and Professor of Immunology at Harvard Medical School since 1997. He is co-editor of Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (currently 22nd edition), the most widely used textbook of medicine in the world, of which he was editor-in-chief of the 16th and 19th editions.