Should I stay or should I go: Hospital germ’s dual strategy

Why P. aeruginosa is successful in colonizing surfaces

Advertisement

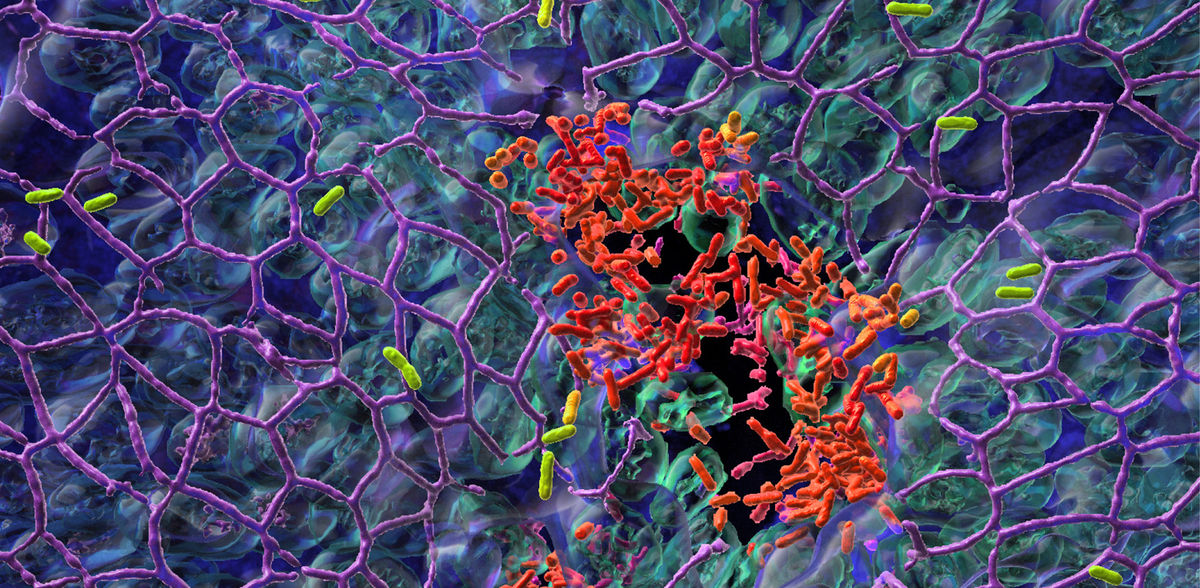

infections are among the most frequent complications during a hospital stay. Researchers at the University of Basel have now uncovered why one of the most dangerous nosocomial pathogens is so difficult to combat. It follows a dual strategy, with some bacteria colonizing the tissue surface while others spread in the body. The study provides important insights into the infection process and opens up new ways to treat infections.

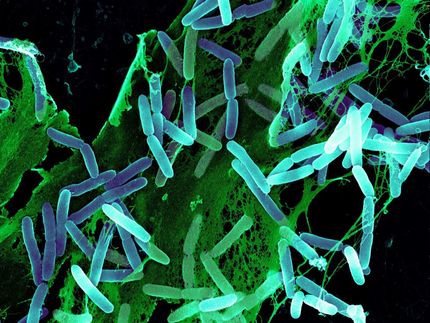

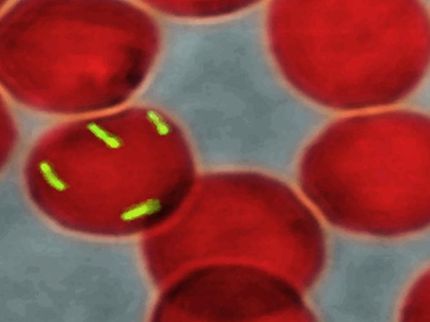

In Switzerland, it is not uncommon for a patient to develop an infection during a hospital stay. One reason for this is insufficient hygiene, as shown recently in a study by the Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products, Swissmedic. Every year, about 6000 patients die from nosocomial infections. One pathogen of major concern is Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This resistant bacterium colonizes the skin and mucosal surfaces and can cause life-threatening pneumonia particularly in immunocompromised patients.

The research team of Professor Urs Jenal at the Biozentrum, University of Basel, has now discovered why P. aeruginosa is successful in colonizing surfaces: it practices a division of labor. While one fraction of the bacterial population adheres to the mucosal surface and forms a biofilm, the other subpopulation spreads to distant tissue sites. Through this “job sharing” process, the pathogens increase their surface colonization success. Protected in a biofilm, they can even resist antibiotic treatments.

Division of labor: motile and sessile bacteria

In their study, recently published in «Nature Microbiology», the scientists report on a stochastic genetic switch that responsible for the division of labor and thus the lifestyle of bacteria – motile or sessile. After initial surface colonization, the pathogens do not simply divide at random, but rather form two functionally distinct subpopulations.

This behavior is regulated by different levels of the bacterial signaling molecule c-di-GMP. Bacteria with high levels of c-di-GMP attach to surfaces and form a robust biofilm, while bacteria with low levels are motile and disperse into the surrounding tissue to colonize other parts of the host tissue. The concentration of c-di-GMP and consequently the behavior of the bacteria is regulated by this stochastic switch.

“Stick and run” mechanism

“The division-of-labor strategy enables the bacteria to rapidly respond to different stress conditions, because at any given time, a fraction of cells is optimally adapted to survive,” explains Dr. Christina Manner, first author of the study. Bacteria in biofilm communities, for example, are protected from attacks by immune cells, while the fraction of dispersing motile bacteria can conquer new ground. This division of labor is also known as the “stick and run” mechanism.

“We now better understand, how Pseudomonas aeruginosa manages to spread and thrive on lung mucosa”, says the project leader Urs Jenal. “By identifying the genetic switch, we have tracked down the Achilles heel of the pathogen”. The study not only provides valuable insights into the infection process but also reveals new therapeutic options to control infections with this dangerous nosocomial pathogen.

“We were also able to show that the recently discovered anti-biofilm compound Disperazol targets the same mechanism and flips the switch in favor of motile Pseudomonas cells, leading to biofilm dispersal,” adds Jenal. “This is a major step forward, as such agents open up new ways to eradicate difficult-to-treat biofilm infections.”

Original publication

Christina Manner, Raphael Dias Teixeira, Dibya Saha, Andreas Kaczmarczyk, Raphaela Zemp, Fabian Wyss, Tina Jaeger, Benoit-Joseph Laventie, Sebastien Boyer, Jacob G. Malone, Katrine Qvortrup, Jens Bo Andersen, Michael Givskov, Tim Tolker-Nielsen, Sebastian Hiller, Knut Drescher & Urs Jenal; A genetic switch controls Pseudomonas aeruginosa surface colonization; Nature Microbiology; 2023