Poorly insulated nerve cells promote Alzheimer’s disease in old age

The results of the study show, for the first time, that defective myelin in the aging brain increases the risk of Aꞵ peptide deposition

Alzheimer’s disease, an irreversible form of dementia, is considered the world’s most common neurodegenerative disease. The prime risk factor for Alzheimer’s is age, although it remains unclear why. It is known that the insulating layer around nerve cells in the brain, named myelin, degenerates with age. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Multidisciplinary Sciences in Göttingen have now shown that such defective myelin actively promotes disease-related changes in Alzheimer’s. Slowing down age-related myelin damage could open up new ways to prevent the disease or delay its progression in the future.

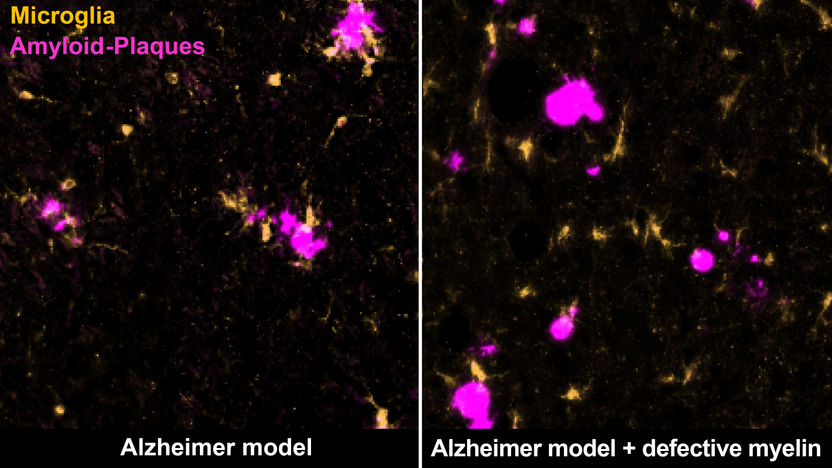

Certain immune cells, microglia (yellow), remove amyloid plaques (magenta) in the brain of an Alzheimer mouse (left). Degenerating myelin distracts them from doing so (right).

Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences

What was I about to do? Where did I put the keys? When was that appointment again? It starts with slight memory lapses, followed by increasing problems to orient, to follow conversations, to articulate, or to perform simple tasks. In the final phase, patients are most often care-dependent. Alzheimer’s disease progresses gradually and mainly affects the elderly. The risk of developing Alzheimer’s doubles every five years after the age of 65.

Signs of aging in the brain

“The underlying mechanisms that explain the correlation between age and Alzheimer’s disease have not yet been elucidated,” says Klaus-Armin Nave, director at the MPI for Multidisciplinary Sciences. With his team of the Department of Neurogenetics, he investigates the function of myelin, the lipid-rich insulating layer of the brain’s nerve cell fibers. Myelin ensures the rapid communication between nerve cells and supports their metabolism. “Intact myelin is critical for normal brain function. We have shown that age-related changes in myelin promote pathological changes in Alzheimer’s disease,” Nave continues.

In a new study now published in the scientific journal Nature, the scientists explored the possible role of age-related myelin degradation in the development of Alzheimer’s. Their work focused on a typical feature of the disease: “Alzheimer’s is characterized by the deposition of certain proteins in the brain, the so-called amyloid beta peptides, or Aꞵ peptides for short,” states Constanze Depp, one of the study’s two first authors. “The Aꞵ peptides clump together to form amyloid plaques. In Alzheimer’s patients, these plaques form many years and even decades before the first symptoms appear.” In the course of the disease, nerve cells finally die irreversibly and the transmission of information in the brain is disturbed.

Using imaging and biochemical methods, the scientists examined and compared different mouse models of Alzheimer’s in which amyloid plaques occur in a similar way to those in Alzheimer’s patients. For the first time, however, they studied Alzheimer’s mice that additionally had myelin defects, which also occur in the human brain at an advanced age.

Ting Sun, second first author of the study, describes the results: “We saw that myelin degradation accelerates the deposition of amyloid plaques in the mice’ brains. The defective myelin stresses the nerve fibers, causing them to swell and produce more Aꞵ peptides.”

Overwhelmed immune cells

At the same time, the myelin defects attract the attention of the brain’s immune cells called microglia. “These cells are very vigilant and monitor the brain for any sign of impairment. They can pick up and destroy substances, such as dead cells or cellular components,” Depp adds. Normally, microglia detect and eliminate amyloid plaques, keeping the buildup at bay. However, when microglia are confronted with both defective myelin and amyloid plaques, they primarily remove the myelin remnants while the plaques continue to accumulate. The researchers suspect that the microglia are ‘distracted’ or overwhelmed by the myelin damage, and thus cannot respond properly to plaques.

The results of the study show, for the first time, that defective myelin in the aging brain increases the risk of Aꞵ peptide deposition. “We hope this will lead to new therapies. If we succeeded in slowing down age-related myelin damage, this could also prevent or slow down Alzheimer’s disease,” Nave says.