Biocomputers powered by human brain cells?

Despite AI’s impressive track record, its computational power pales in comparison with a human brain. Now, scientists unveil a revolutionary path

artificial intelligence (AI) has long been inspired by the human brain. This approach proved highly successful: AI boasts impressive achievements – from diagnosing medical conditions to composing poetry. Still, the original model continues to outperform machines in many ways. This is why, for example, we can ‘prove our humanity’ with trivial image tests online. What if instead of trying to make AI more brain-like, we went straight to the source?

Symbolic image

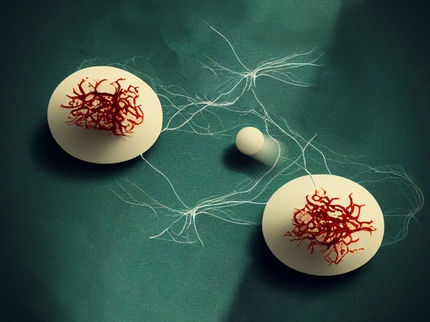

Computer-generated image

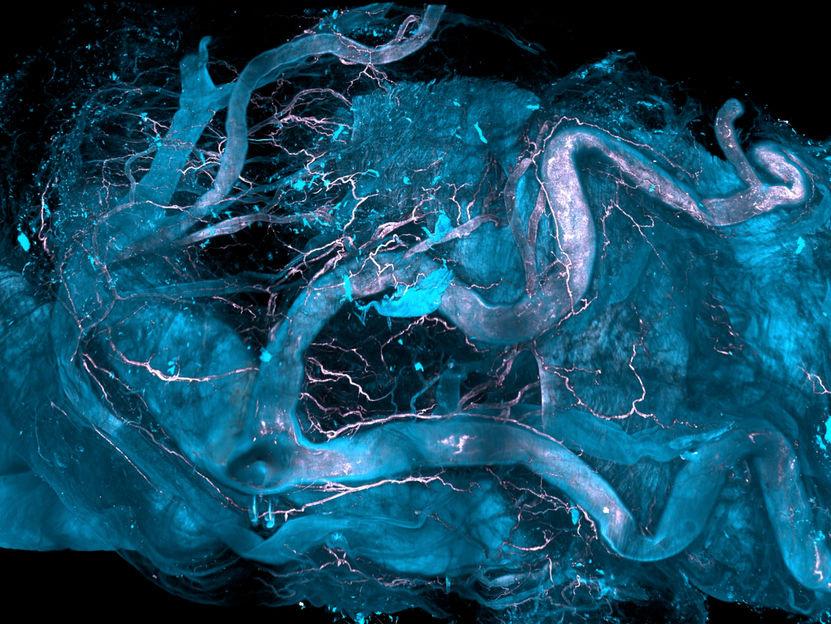

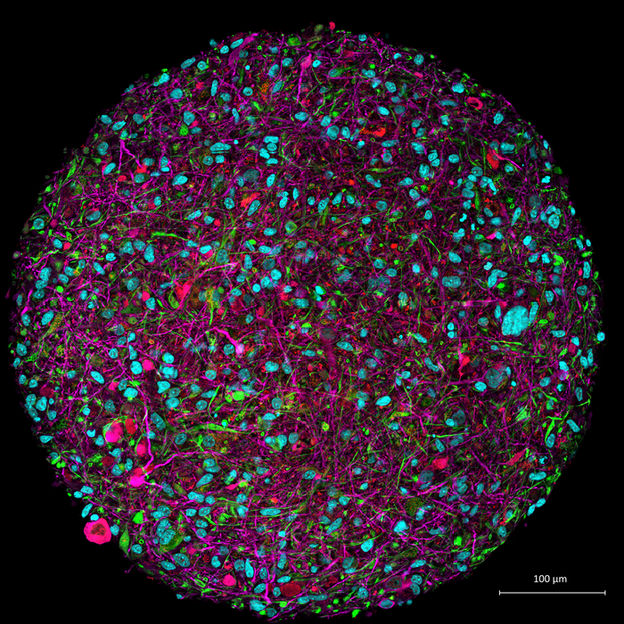

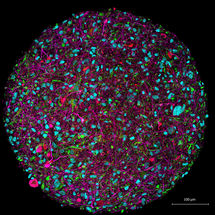

A magnified image of a lab-grown brain organoid with fluorescent labeling for different cell types. (Pink - neurons; red - oligodendrocytes; green - astrocytes; blue - all cell nuclei)

Thomas Hartung, Johns Hopkins University

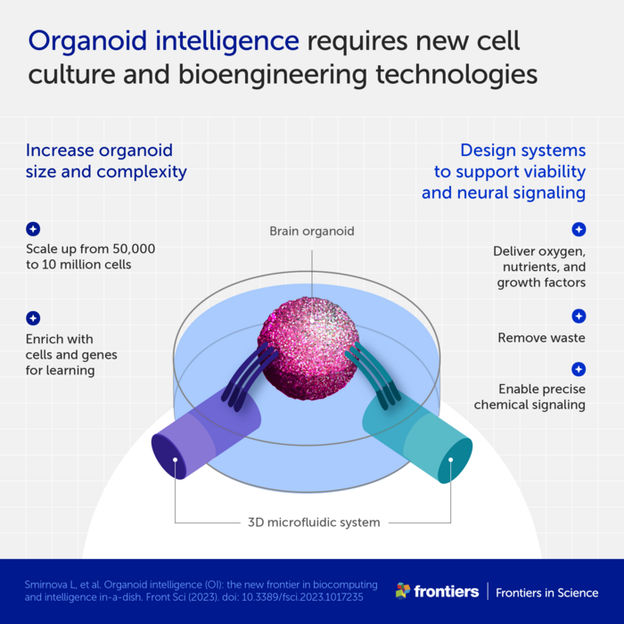

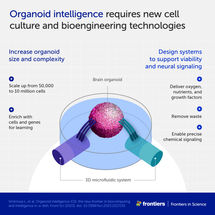

Infographic: Organoid intelligence: The new frontier in biocomputing

Frontiers/John Hopkins University

Scientists across multiple disciplines are working to create revolutionary biocomputers where three-dimensional cultures of brain cells, called brain organoids, serve as biological hardware. They describe their roadmap for realizing this vision in the journal Frontiers in Science.

“We call this new interdisciplinary field ‘organoid intelligence’ (OI),” said Prof Thomas Hartung of Johns Hopkins University. “A community of top scientists has gathered to develop this technology, which we believe will launch a new era of fast, powerful, and efficient biocomputing.”

What are brain organoids, and why would they make good computers?

Brain organoids are a type of lab-grown cell-culture. Even though brain organoids aren’t ‘mini brains’, they share key aspects of brain function and structure such as neurons and other brain cells that are essential for cognitive functions like learning and memory. Also, whereas most cell cultures are flat, organoids have a three-dimensional structure. This increases the culture's cell density 1,000-fold, meaning that neurons can form many more connections.

But even if brain organoids are a good imitation of brains, why would they make good computers? After all, aren't computers smarter and faster than brains?

"While silicon-based computers are certainly better with numbers, brains are better at learning,” Hartung explained. “For example, AlphaGo [the AI that beat the world’s number one Go player in 2017] was trained on data from 160,000 games. A person would have to play five hours a day for more than 175 years to experience these many games.”

Brains are not only superior learners, they are also more energy efficient. For instance, the amount of energy spent training AlphaGo is more than is needed to sustain an active adult for a decade.

“Brains also have an amazing capacity to store information, estimated at 2,500TB,” Hartung added. “We’re reaching the physical limits of silicon computers because we cannot pack more transistors into a tiny chip. But the brain is wired completely differently. It has about 100bn neurons linked through over 1015 connection points. It’s an enormous power difference compared to our current technology.”

What would organoid intelligence bio computers look like?

According to Hartung, current brain organoids need to be scaled-up for OI. "They are too small, each containing about 50,000 cells. For OI, we would need to increase this number to 10 million,” he explained.

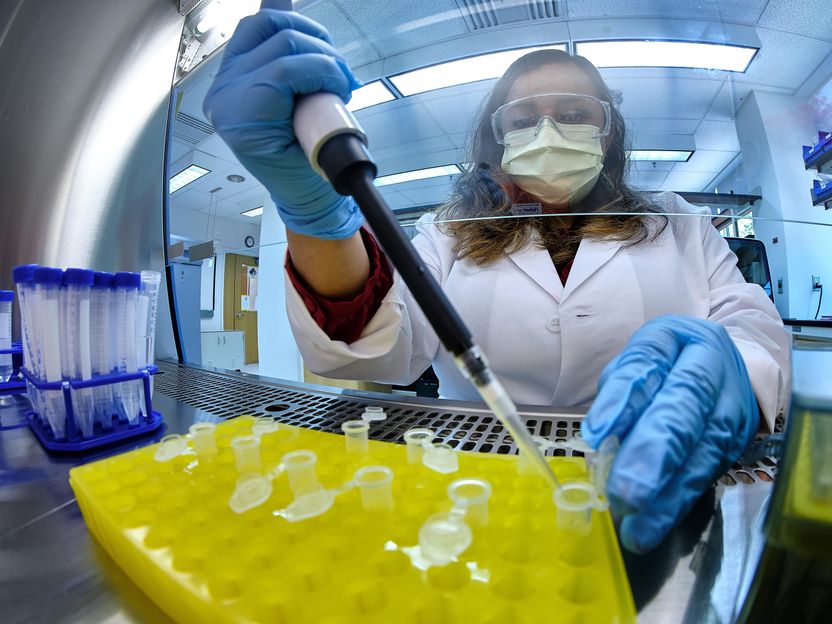

In parallel, the authors are also developing technologies to communicate with the organoids: in other words, to send them information and read out what they’re ‘thinking’. The authors plan to adapt tools from various scientific disciplines, such as bioengineering and machine learning, as well as engineer new stimulation and recording devices.

“We developed a brain-computer interface device that is a kind of an EEG cap for organoids, which we presented in an article published last August. It is a flexible shell that is densely covered with tiny electrodes that can both pick up signals from the organoid, and transmit signals to it,” said Hartung.

The authors envision that eventually OI would integrate a wide range of stimulation and recording tools. These will orchestrate interactions across networks of interconnected organoids that implement more complex computations.

Organoid intelligence could help prevent and treat neurological conditions

OI’s promise goes beyond computing and into medicine. Thanks to a groundbreaking technique developed by Noble Laureates John Gurdon and Shinya Yamanaka, brain organoids can be produced from adult tissues. This means that scientists can develop personalized brain organoids from skin samples of patients suffering from neural disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease. They can then run multiple tests to investigate how genetic factors, medicines, and toxins influence these conditions.

“With OI, we could study the cognitive aspects of neurological conditions as well,” Hartung said. “For example, we could compare memory formation in organoids derived from healthy people and from Alzheimer’s patients, and try to repair relative deficits. We could also use OI to test whether certain substances, such as pesticides, cause memory or learning problems.”

Taking ethical considerations into account

Creating human brain organoids that can learn, remember, and interact with their environment raises complex ethical questions. For example, could they develop consciousness, even in a rudimentary form? Could they experience pain or suffering? And what rights would people have concerning brain organoids made from their cells?

The authors are acutely aware of these issues. “A key part of our vision is to develop OI in an ethical and socially responsible manner,” Hartung said. “For this reason, we have partnered with ethicists from the very beginning to establish an ‘embedded ethics’ approach. All ethical issues will be continuously assessed by teams made up of scientists, ethicists, and the public, as the research evolves.”

How far are we from the first organoid intelligence?

Even though OI is still in its infancy, a recently-published study by one of the article’s co-authors – Dr Brett Kagan of the Cortical Labs – provides proof of concept. His team showed that a normal, flat brain cell culture can learn to play the video game Pong.

“Their team is already testing this with brain organoids,” Hartung added. “And I would say that replicating this experiment with organoids already fulfills the basic definition of OI. From here on, it’s just a matter of building the community, the tools, and the technologies to realize OI’s full potential,” he concluded.