Exciting breakthrough: Antibiotic innovation helps fight against superbugs

Scientists have created a new type of antibiotic that can be rapidly re-engineered to avoid resistance by dangerous superbugs

Developed by PhD candidate Priscila Cardoso and principal supervisor Dr Céline Valéry from RMIT’s School of Health and Biosciences, the antibiotic has a simple design that allows it to be produced quickly and cost-effectively in a lab.

A vial of Priscilicidin on a gloved hand.

RMIT University

Named Priscilicidin, the antibiotic’s amino acid building blocks are small, so it can be tailored to tackle different types of antimicrobial resistance.

With the World Health Organization calling antimicrobial resistance “one of the top ten global public health threats facing humanity”, developing new antibiotics is more urgent than ever.

Professor Charlotte Conn, one of Cardoso’s PhD supervisors, said given that urgency, Priscilicidin was an exciting breakthrough for public health.

Priscilicidin is a type of antimicrobial peptide. These peptides are produced by all living organisms as the first defense against bacteria and viruses.

After reviewing the literature on antimicrobial peptide molecular engineering, the team designed and tested 20 short peptides before settling on Priscilicidin as the best candidate.

“The pharmaceutical industry generally tests thousands of compounds before getting a lead candidate. In our case, only 20 designs were necessary to create an entire new family of antibiotics,” Valéry said.

Conn said Priscilicidin was based on a natural antibiotic peptide, which made it less likely to cause antimicrobial resistance compared to existing conventional antibiotics.

“Current natural antibiotics are expensive and difficult to make on a large scale. They also break down quickly in the body,” she said

“Priscilicidin combines the advantages of small molecular design, which means it’s quick and inexpensive to synthesise in a lab, with the advantages of natural antibiotics.”

How does Priscilicidin work?

Priscilicidin was derived from Indolicidin, a natural antibiotic found in cows’ immune systems.

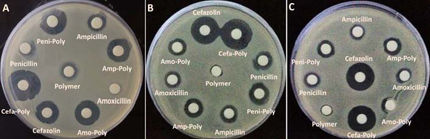

The team’s research, published in January 2023 in the Women in Nanoscience 2022 special issue of Frontiers in Chemistry, showed Priscilicidin was highly active against resistant microbial strains such as golden staph, E. coli bacteria and candida fungi.

Priscilicidin works by disturbing the membrane of the microbes, eventually killing the cell. “Attacking this outer layer makes it harder for the bacteria to evolve and resist treatment,” said Valéry.

Lab tests showed Priscilicidin had a similar antimicrobial activity as Indolicidin on common bacterial and fungal infections.

A new arsenal of topical and oral antibiotics

The team’s research shows Priscilicidin’s molecules naturally self-assemble into hydrogel form, making it ideal for creating antibiotic gels and creams.

Valéry said when new drugs were created, scientists needed to consider the drug’s pharmaceutical formulation.

This includes the drug’s form (capsule or cream, for example) and processes involved.

Priscilicidin’s natural hydrogel form meant they can bypass some of that formulation process, Valéry said.

“The fact we can control the viscosity of Priscilicidin means we can contemplate many applications as different products, diversifying the types of treatments to stop antimicrobial resistance,” she said.

While the team are predominantly investigating Priscilicidin for topical applications, they are not ruling out oral applications.

“In theory, you could choose all means of administration for Priscilicidin, but none of them have been tested yet,” Conn said.

“We have an oral delivery technology at RMIT for protein and peptide drugs, which will allow antimicrobial peptides to be administered orally. We are currently looking at Priscilicidin as a candidate for this test.”